Va’yetar Yitzchok l’Hashem l’nochach ishto ki akara hee va’yei’aseir lo Hashem va’tahar Rivkah ishto (25:21)

After 20 childless years of marriage, Yitzchok and Rivkah petitioned and beseeched Hashem to give them children. Rashi explains that they didn’t pray as one would typically pray, but rather they entreated Hashem repeatedly and with tremendous fervor before they were finally answered. What was Hashem’s rationale for making them endure such intense and prolonged suffering? Why didn’t He answer their prayers immediately?

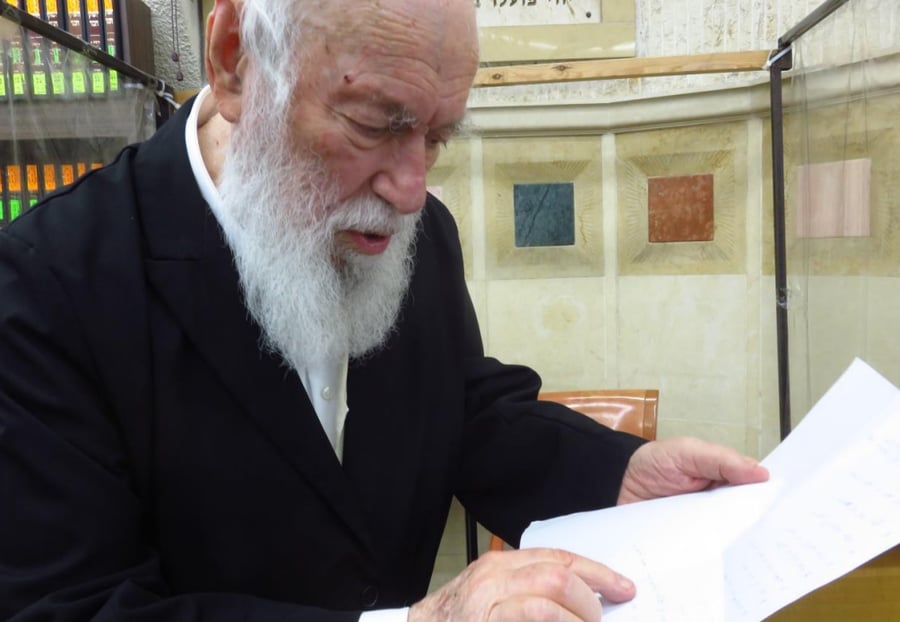

Rav Meir Shapiro and Rav Elyashiv note that Rashi writes (25:30) that Avrohom died five years prematurely so that he wouldn’t have to endure the pain of seeing his grandson Eisav commit terrible sins. Recognizing that this would occur made it incredibly difficult for Hashem to answer the prayers of Yitzchok and Rivkah. Hashem understood that the sooner He would give them the children for which they were pleading, the sooner Eisav would embark upon his path of wickedness, and the sooner His beloved Avrohom would have to die to be spared the anguish of witnessing Eisav’s actions.

Therefore, Hashem put off answering the heartfelt pleas of Yitzchok and Rivkah until they prayed repeatedly with so much intent that He was “forced” to grant their request. Rav Yosef Chaim Zonnenfeld suggests that this explanation is alluded to by the fact that “Va’yei’aseir lo Hashem” – and Hashem was entreated by Yitzchok – has the same numerical value (748) as “chameish shanim” – five years.

Many times in life we are convinced that we need something for the sake of our happiness and well-being. We pray and cry and pray again, eventually becoming frustrated at Hashem’s apparent cruelty in ignoring or rejecting what we feel are heartfelt and reasonable requests. At such times, we should remind ourselves of this lesson and take comfort in the knowledge that sometimes Hashem, in His infinite wisdom and mercy, recognizes that what we are firmly convinced we need and deserve may in reality not be in our own long-term best interest.

Vayisrotz’tzu habanim b’kirbah vatomer im kein lamah zeh anochi vateleich lidrosh es Hashem vayomer Hashem lah shnei goyim b’vitneich u’shnei l’umim mimeiayich yipariedu ul’om mil’om ye’ematz v’rav ya’avod tzair (25:22-23)

After being barren for 20 years, Yitzchok and Rivkah beseeched Hashem to bless them with a child, and Rivkah indeed became pregnant. However, her pregnancy was particularly painful and difficult. Rashi writes that when she passed by the yeshiva of Shem and Ever, the righteous Yaakov struggled to run out, and when she passed a temple of idolatry, the wicked Eisav attempted to come out.

Rivkah, troubled by the complications of her pregnancy, went to seek an explanation from Shem. Shem comforted her by explaining that she was pregnant with twins who would eventually develop into two separate nations that would always be jockeying against one another for supremacy. Although Shem certainly enlightened Rivkah about what was going on inside of her, the reason that she approached him was due to her frustration over her painful pregnancy. How did his explanation about the future help comfort her very real and immediate pain?

Rav Yosef Chaim Zonnenfeld suggests that Shem’s words weren’t merely a prophetic clarification of her perplexing situation, but they also allayed Rivkah’s difficult pregnancy in a very real and tangible way. He explains that Shem concluded his message to her by saying that the descendants of the older son would serve those of the younger son.

The Medrash HaGadol teaches that one of the reasons that Rivkah’s body had been enduring such constant turmoil during her pregnancy was that Yaakov and Eisav were fighting and jockeying for position in order to come out first and enjoy the benefits associated with being the first-born. However, now that they heard Shem’s prophecy that the older son would actually be subordinate to the younger, they ceased fighting with one another, and the pains of Rivkah’s pregnancy were alleviated as a result.

Vayigd’lu ha’nearim vayehi Eisav ish yodeia tzayid ish Sadeh v’Yaakov ish tam yosheiv ohalim (25:27)

Although Yaakov and Eisav were twins, the Torah records that they were polar opposites. Yaakov spent his days dwelling in the study hall to learn Torah, while Eisav focused his energies on hunting animals in the field. Although Rashi writes that these differences weren’t apparent until they matured and reached the age of 13, Chazal tell us that their different values and priorities were already established even before they were born.

The Medrash relates (Yalkut Shimoni 111) that when they were still fetuses in their mother’s womb, Yaakov told Eisav that Hashem created two worlds: the physical world in which we live and the spiritual World to Come. The physical world is full of eating, drinking, doing business, getting married, and having children, none of which may be enjoyed in the World to Come. Yaakov offered to divide the two worlds, with Eisav taking the physical world and Yaakov receiving the spiritual world, an offer to which Eisav was only too happy to agree.

In “Mah Yedidus,” one of the songs traditionally sung on Friday night, we eloquently describe the wonderful delicacies and pleasures of this world, such as fattened chickens and sweet wines, which we enjoy at the Shabbos meal. Curiously, after relating the mouth-watering treats associated with Shabbos, we proudly declare that “Nachalas Yaakov yirash” – a person who properly honors Shabbos in this fashion will inherit the portion of Yaakov. This seems difficult to understand. The Medrash teaches that Yaakov’s share that of the spiritual World to Come. Although Shabbos indeed offers delectable enjoyments, isn’t it dishonest to associate these physical pleasures with Yaakov?

Rav Moshe Wolfson suggests that this song resolves this question just a few stanzas later, when we proclaim that “Me’ein Olam HaBa yom Shabbos menucha” – the restful day of Shabbos is itself so spiritual that it represents a microcosm of the World to Come. As we enjoy the Shabbos delicacies at our meals, we should appreciate and give thanks for this weekly opportunity to enjoy a small taste of the tremendous reward waiting for us – Yaakov’s descendants – in the World to Come.

Vayomer Eisav el Yaakov hal’iteini na min ha’adom ha’adom ha’zeh (25:30)

Parsha Toldos begins with the birth of Yitzchok’s twin sons, Yaakov and Eisav. Shortly thereafter, the Torah records that one day, Eisav came in from the field, tired and exhausted. He saw that Yaakov was cooking a lentil stew, and in his fatigued state, he begged Yaakov to feed him “the red food,” identifying it solely by its color and not even bothering to refer to it by its proper name.

Rav Mattisyahu Salomon relates that he was once in the house of Rav Elozar Menachem Shach and observed Rav Shach, who was well-known for giving candy to children, offering a lollipop to one of his grandchildren, adding, “You want a red one, right?” Rav Mattisyahu interjected, “Isn’t the Rosh Yeshiva encouraging him to be like Eisav, who insisted that Yaakov feed him ‘the red food?'”

Rav Shach, who was capable of imparting valuable lessons and perspectives through even mundane conversations and actions, responded that there was a critical difference between the two cases. He explained that for a child, living in a world of superficial dreams and imagination and preferring a shiny red lollipop is ordinary behavior and is to be expected. Children are only capable of appreciating the external appearance of an object, and there is no problem with recognizing this reality and interacting with them on their level.

The problem, Rav Shach continued, begins when an adult refuses to mature and elects to live his entire life in this shallow manner. As a person grows up, it is expected that his mind will mature as well, enabling him to see and appreciate an item’s internal value. When Eisav requested that Yaakov provide him with “the red food,” he was demonstrating his singular focus on externality and his inability to concern himself with the actual content of the dish.

Although most of us don’t spend our days pursuing red lollipops or red stew, Rav Shach’s message is still relevant to each of us. As children, we were drawn toward flash and superficiality, as could be expected of us at that time. However, as we age, it is imperative to transition to a more mature outlook and perspective, recognizing that people, possessions, and accomplishments should not be judged by their external appearance, but by their deeper – and true – value.

Answers to the weekly Points to Ponder are now available!

To receive the full version with answers email the author at [email protected].

Parsha Points to Ponder (and sources which discuss them):

1) The Arizal teaches that Shimshon was a combination of the souls of Yefes and Eisav. In what way did Shimshon rectify their sins and errors?

2) Rashi writes (27:9) that one of the two goats which Rivkah commanded Yaakov to bring served as Yitzchok’s Korban Pesach (Passover sacrifice). What was Rivkah’s hidden intention in doing so? (Chochmas Chaim)

3) If Yitzchok knew that his brother-in-law Lavan was wicked, why did he instruct Yaakov (28:2) to marry one of his daughters? (Moshav Z’keinim)

4) Rashi writes (25:9) that Yishmael repented his sins before the death of his father Avrohom. Why did he subsequently allow (28:9) the wicked Eisav to marry his daughter? (Emunas Yirmiyah)

© 2013 by Oizer Alport.