Ki ha’aretz asher atah ba shamah l’rishtah lo k’eretz Mitzrayim hu asher y’tzasem misham asher tizra es zarecha v’hishkisa b’raglecha k’gan hayarek v’ha’aretz asher atem ovrim shama l’rishtah eretz harim uv’kaos lim’tar haShomayim tishteh mayim (11:10-11)

Moshe stressed to the Jewish people that the land of Israel would be different than the land of Egypt from which they were coming. Whereas the fields of the land of Egypt were watered by irrigation from the Nile River, those in Israel received their water from the rain. Although Rashi notes that a natural water supply is advantageous in that it requires substantially less exertion, what deeper message was Moshe trying to impart?

After tempting Chava to eat from the forbidden Tree of Knowledge, the serpent was cursed that it would travel on its stomach and eat dust all the days of its life (Bereishis 3:14). In what way does this represent a punishment, as other animals must spend days hunting for prey while the snake’s diet – dust – can be found wherever it travels?

The Kotzker Rebbe explains that this point is precisely the curse. Other animals are dependent on Hashem to help them find food to eat. The snake, on the other hand, slithers horizontally across the earth. It never goes hungry, never looks upward, and is totally cut off from a relationship with Hashem, and therein lies the greatest curse imaginable.

Similarly, Rav Shimshon Pinkus symbolically explains that Moshe wasn’t merely relating an agricultural fact. He was teaching that just like the serpent, the Egyptians were a totally “natural” people. Because it never rained in their country, so they never had to look skyward to see what the clouds foretold. As a result, their hearts never gazed toward the Heavens, which effectively cutting them off from perceiving any dependence on or relationship with the Almighty. Everything which occurred in their lives could be explained scientifically and deceptively appeared to be completely “natural.”

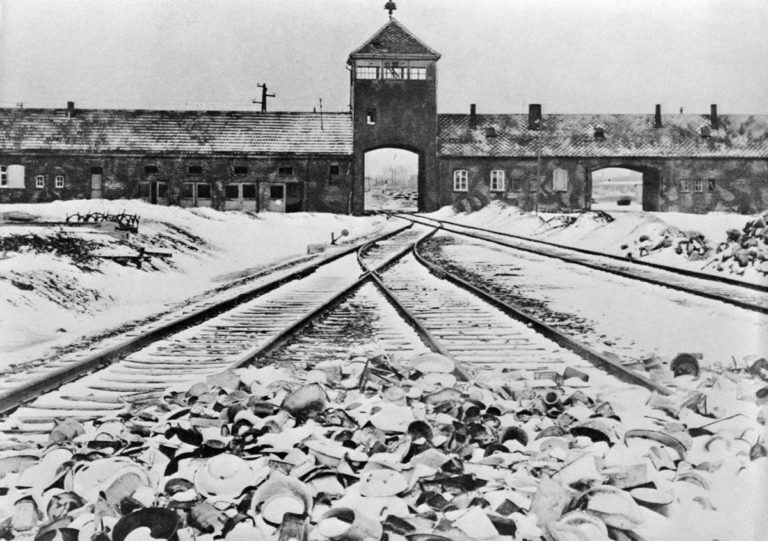

In light of this, the Exodus from Egypt to Israel wasn’t merely a physical redemption from agonizing enslavement, but it also represented a deeper philosophical departure. The Exodus allowed the fledgling Jewish nation to exchange a worldview devoid of spirituality, through which everything is understood and explained according to science and nature, for one in which we confidently declare that Hashem runs every aspect of the universe and we are dependent on Him for every detail of our daily lives.

Eretz asher Hashem Elokecha doreish osah tamid einei Hashem Elokecha bah me’reishis ha’shana v’ad acharis shana (11:12)

The Gemora in Rosh Hashana (16b) teaches that any year which is “poor” at the beginning will be rich and full of blessing at the end. This is homiletically derived from our verse, which refers to the beginning of the year as “reishis ha’shana” (leaving out the letter “aleph” in the word “reishis”), which may be reinterpreted as a poor year (“rash” means poor). The Gemora understands the Torah as hinting that such a year will have an ending different than that with which it began (i.e. rich and bountiful).

As Rosh Hashana grows ever closer, what does this valuable advice mean, and how can we use it to ensure that the coming year will be a prosperous one for us and our loved ones? Rashi explains that a “poor” year refers to one in which a person makes himself poor on Rosh Hashana to beg and supplicate for his needs. In order to follow this advice, we must first understand what it means to make oneself like a poor person.

Rav Chaim Friedlander explains that it isn’t sufficient to merely view oneself “as if” he is poor for the day. A person must honestly believe that his entire lot for the upcoming year – his health, happiness, and financial situation – will be determined on this day. In other words, at the present moment, he has absolutely nothing to his name and must earn it all from scratch. This may be difficult to do for a person who is fortunate enough to have a beautiful family, a good source of income, and no history of major medical problems. How can such a person honestly stand before Hashem and view himself as a pauper with nothing to his name?

Rav Friedlander explains that if a person understands that all that he has is only because Hashem willed it to be so until now, he will recognize that at the moment Hashem wills the situation to change, it will immediately do so. Although we are accustomed to assuming that this couldn’t happen to us, most of us personally know of stories which can help us internalize this concept.

I once learned this lesson the hard way on a trip to Israel. Shortly after arriving in Jerusalem, I took a taxi to the Kosel. My enthusiasm quickly turned to shocked disbelief when I suddenly realized that I’d forgotten my wallet in the back seat of the cab. Numerous frantic calls to the taxi’s company bore no fruit, and instead of proceeding to pray at the Kosel, I had to first stop to call my bank to cancel my credit cards. Looking back a few years later, I realize that I painfully learned that just because I had something and assumed it to be firmly in my possession, I shouldn’t rely on this belief and take if for granted.

On Rosh Hashana, Hashem decrees what will happen to every person at every moment of the upcoming year, including what they will have and to what extent they will be able to enjoy it. Each person begins the year with a clean slate and must merit receiving everything which he had until now from scratch. If we view ourselves standing before Hashem’s Throne of Glory like a poor person with nothing to our names, we will realize that our entire existence in the year to come is completely dependent on Hashem’s kindness. A person who genuinely feels this way can’t help but beg and plead for Divine mercy. The Gemora promises that if he does so, Hashem will indeed be aroused to give him a decree of a wonderful year, something that we should all merit in the coming year.

Parsha Points to Ponder (and sources which discuss them):

1) How can Hashem promise (7:15) to remove from us all illnesses if we perform the mitzvos when the Gemora in Bava Metzia (57b) teaches that everything is in the hands of Heaven except for sickness? (Tosefos Kesuvos 30a, Paneiach Raza)

2) In enumerating the seven species for which the land of Israel is praised, why does the Torah refer (8:8) to the extracts of olives and dates and not to the fruits themselves, as it does in reference to the other species for which the land of Israel is praised? (Maharsha Horayos 13b)

3) Although the Torah requires a person to say the Grace after Meals after eating (8:10), the obligation to recite blessings prior to eating is only Rabbinical in nature. In what way are the blessings said after eating more important than those said before?

4) The Gemora in Berachos (35b) teaches that eating without reciting the appropriate blessing is considered a form of stealing. Why aren’t non-Jews, who are also forbidden to steal, similarly obligated to recite blessings (8:10) before and after their meals?

5) The Gemora in Menachos (43b) derives from 10:12 that one is required to recite 100 blessings daily. For the purposes of this mitzvah, does a day begin at sunrise or sundown, and if it begins at sunrise, why is it different than other mitzvos for which the Jewish day traditionally begins at sundown? (Shu”t B’tzeil HaChochmah 4:155, Shu”t Yabia Omer 10:7, Piskei Teshuvos 46:9)

6) The Gemora in Taanis (2a) derives from 11:13 the obligation to pray to Hashem. It is the opinion of the Rambam (Hilchos Tefillah 1:1) that this is a Biblical obligation, although he maintains that one is Biblically required to pray only one time daily at any time of the day. Why isn’t the Rabbinical enactment to pray three times a day at fixed times considered a violation of the prohibition (4:2) against adding on to the mitzvos? (Halichos Shlomo Tefillah Vol. 1 pg. 1)

7) Did the Jewish people recite Shema and wear tefillin throughout their 40-year wandering in the wilderness, and if so, from where did they know what to say and write, as the first two paragraphs weren’t taught to them until the end of Moshe’s life?

© 2011 by Oizer Alport.