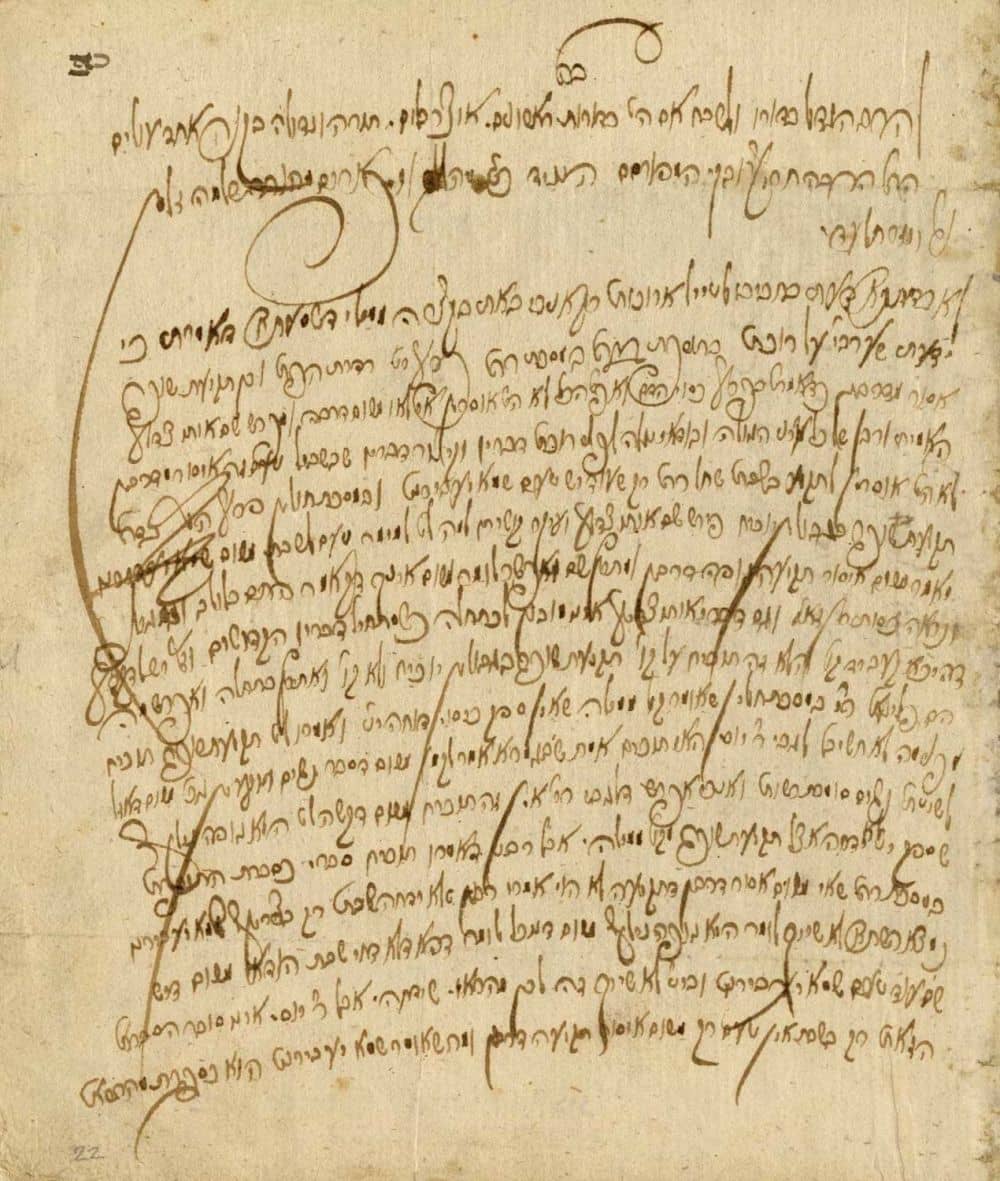

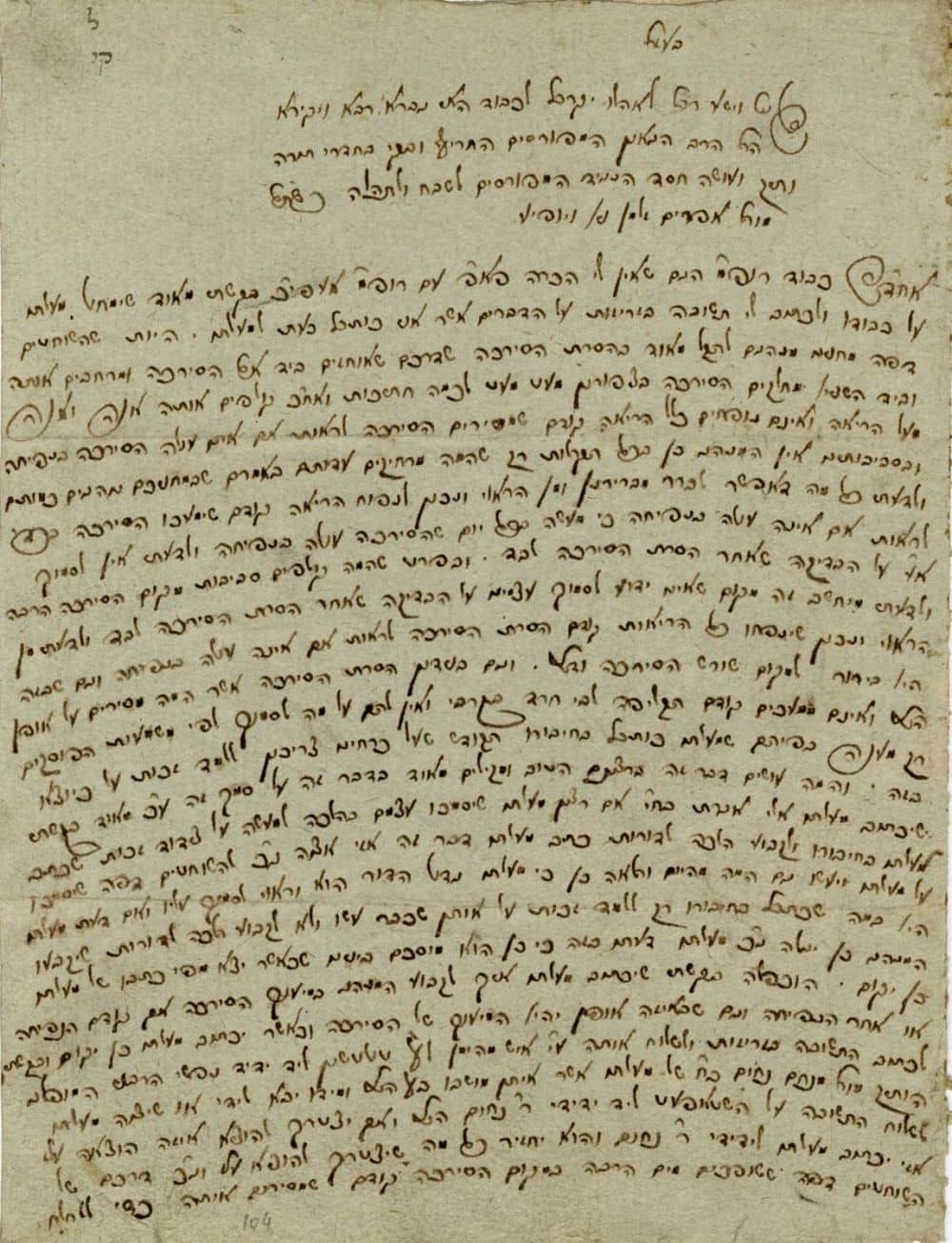

This responsum discusses the prayer nusach (version) and the preference for “Nusach Ar”i” over “Nusach Ashkenaz.” It was printed in Rabbi Chaim Halberstam’s famous book, the Divrei Chaim responsa, part II, section 8. Yet careful comparison of the original text vs. the printed version reveals dozens of differences – sometimes significant ones – between the two, emphasizing the double significance of this original letter, which discusses an issue that is close to the nation’s heart.

Discussions arose regarding prayer version as soon as Chassidut emerged in the 18th century. One of the prominent features of the Chassidic movement is expressed in this shift from “Nusach Ashkenaz,” – the version customarily used in Europe – to “Nusach Ar”i,” also known as “Nusach Sephard.” Nusach Sephard prayer books are based on Nusach Ashkenaz, with some changes and additions to prayers. This was all influenced by the Chassidic movement, which viewed the Ar”i’s kabbalah and his intentions in prayer as of extreme importance – to the extent that they used it to change the version of prayers as they had traditionally prayed them for hundreds of years. The first prayer book printed by the Chassidim was the Siddur HaRav MiLiadi, which was arranged according to Nusach Ar”i (Sklow, 1803). A Nusach Sephard siddur was printed in the Ukraine, Poland, and Galicia that was very different than the Siddur HaRav MiLiadi, corresponding to the opinions in the various Chassidic courts.

The shift from Nusach Ashkenaz to Nusach Sephard triggered a sharp controversy between the Chassidim and their opponents, and even among the Chassidic courts. One of the primary claims in the polemic opposing Chassidism was this shift in version of prayer, a shift which opposed halachah and that many believed was even contrary to the opinion of the Ar”i himself. This claim was mentioned in the first polemic publications, such as Zamir Aritzim V’Chorvot Tzurim, (Oleksinetz 1872): “Our brothers of the house of Israel, did you not know that new matters have come about that our fathers did not know, that a suspicious faction has joined together […] and they are making societies amongst themselves and their religion is different from the whole Jewish nation in their versions of prayer.” The first one to appreciate the importance of adapting the Nusach Sephard changes into the Ashkenazic siddur was Rabbi Dov Ber, the Maggid of Mezeritch, disciple and successor of the Ba’al Shem Tov, who viewed this issue from a kabbalistic point of view. He determined: “And the G-dly Ariza”l, to whom paths of the heavens were known, taught wisdom to the nation for those who did not recognize it … and he instituted the service compiled from a number of versions as known to experts. Therefore, everyone should grasp the path of the Ariza”l, which is good for every soul.” (Maggid Devarav L’Yaakov, Korzec, 1884, leaf 22.)

Despite this, there was no consensus among halachic personalities regarding these changes to the nusach. One of the basic positions on the issue was expressed by a prominent rabbinic leader of the 18th century, Rabbi Moshe Sofer, who wrote in his Chatam Sofer responsa (Orach Chaim 1, siman 15) that the Ar”i wrote his intentions based on the Sephardic version of the prayer book because he was Sephardic, and they do not match the Ashkenazic prayer books. Therefore, only unique, rare personalities have the ability to make these changes: “And when the G-dly light, the Ar”i ztz”l researched and revised because he knew the content, he placed everything correctly in his siddur and revealed mysteries of the Sephardic version because he was Sephardic […] and my teacher the gaon … Natan Adler ztz”l led the prayers himself in the Sephardic version in the Ar”i’s prayer book, and the same is true of my teacher the gaon, the author of Hafla’ah, ztz”l. They were the only ones who prayed in Nusach Ar”i, and no other people in the minyan recited anything other than the Ashkenazic […], because someone who does not have this knowledge, cannot change our nusach.”

The Chatam Sofer’s clear position was before the Divrei Chaim when the latter wrote this famous responsum. In the responsum, he discusses the Chatam Sofer’s claims one by one, while clarifying that he wasn’t trying to disagree with the Chatam Sofer: “I am not an expert [even] in his mundane discussion, only what I saw and received from the mouths of the holy and lofty great ones in the revealed and in the hidden [aspects of the Torah].” At the conclusion of the responsum, the Divrei Chaim determines that, “anyone whose soul is refined can rely on the leaders of the generation, the holy ones, who shifted from Nusach Ashkenaz to Nusach Sephard. Since the Besh”t arrived and grasped onto the Nusach Ar”i, everyone who believes in the Besh”t and his disciples is worthy of grasping the Nusach Ar”i and should not budge from it.”

The controversy surrounding the version of prayer didn’t end with this responsum. It generated the sharp rebuttal of Maharam Schick, disciple of the Chatam Sofer. In his responsa (Orach Chaim 43), he strongly opposes the Divrei Chaim’s determination and concludes: “and I am very astonished that the gaon of Sanz agreed to the opposite, that it is permissible to change.” In contrast, the author of Minchat Elazar of Munkacs argued against the position of the Maharam Schick and supported the Divrei Chaim. https://winners-auctions.bidspirit.com/?lang=en#catalog~42~57~23082

Besides this letter, there are a few more interesting letters for sale:

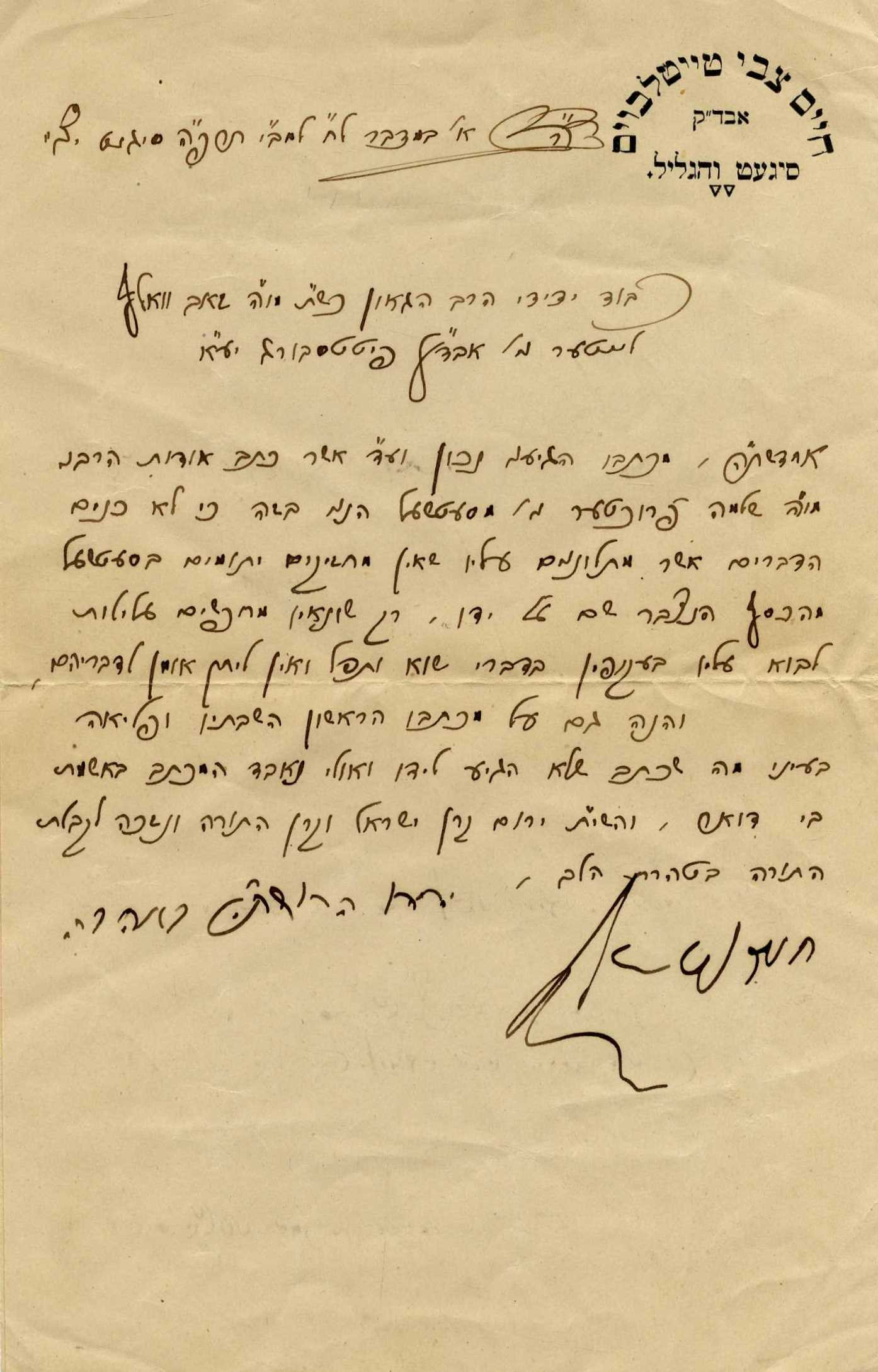

· Letter written and signed by Rabbi Daniel David of Ṭshiṭelniḳ

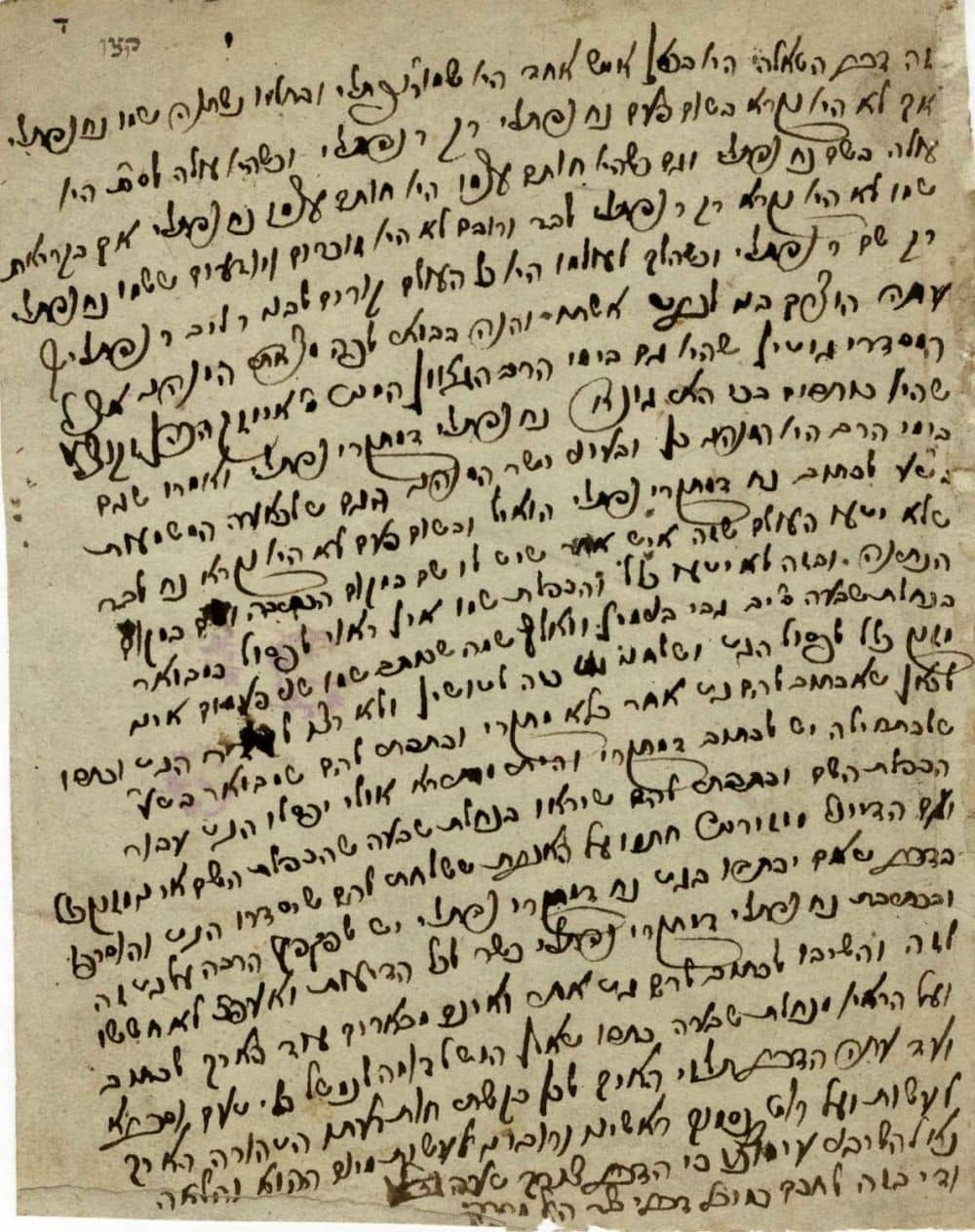

· Rare letter from the first Admor of Narol – Rabbi Yaakov Reiman, to the Beit Ephraim