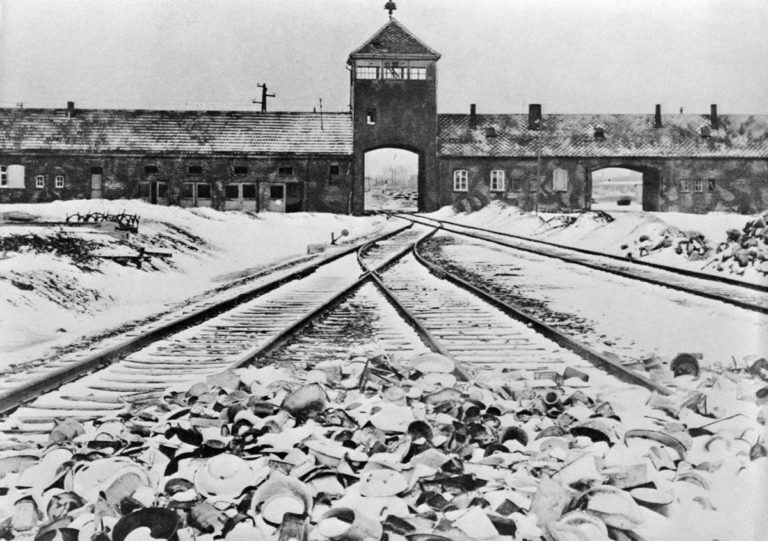

Through much of World War II, Jozef Paczynski cut the hair of Auschwitz commandant Rudolf Hoess, one of the most cold-blooded and sadistic mass murders in Adolf Hitler’s regime.

Through much of World War II, Jozef Paczynski cut the hair of Auschwitz commandant Rudolf Hoess, one of the most cold-blooded and sadistic mass murders in Adolf Hitler’s regime.

Every seven to 10 days the Polish prisoner was taken to Hoess’s villa on the edge of the camp, where he trimmed the killer’s hair using scissors and razors. Never once did Hoess exchange words with the young man whom he had chosen as his personal barber.

For years Paczynski has been asked why he didn’t slit the throat of the man sending hundreds of thousands of innocent people to their deaths at the largest and most notorious Nazi death camp.

Paczynski says it would have done no good: he and many others would have been killed in retribution while the exterminations at Auschwitz would have continued under another commander.

“I thought about it,” Paczynski said. “But when I realized what the consequences would be I simply could not do it.”

The sprightly 95-year-old told his story to a group in Krakow that included two other Auschwitz survivors and a number of Americans in southern Poland after recent commemorations for the 70th anniversary of the liberation of Auschwitz.

Those survivors who still have the strength keep telling their stories to fascinated audiences, with a palpable urgency on both sides to have these stories told while it is still possible.

After Paczynski’s talk, the two other survivors exchanged memories with him and posed for photos together, pulling up their sleeves to reveal the prison numbers tattooed on their forearms.

Paczynski, who lives in Krakow, was imprisoned at Auschwitz in June 1940 as punishment for trying to flee occupied Poland to join the Polish army in France. He was arrested after crossing into Slovakia and was taken in the first transport to Auschwitz, becoming prisoner number 121.

He was assigned to work in a barber shop where the SS men got their haircuts. One day Hoess showed up and ordered the “small Pole” — “der kleine Pole” — to come to his home.

It was with terror that Pacyznski went to the villa, escorted by a guard.

“Hoess’ wife let me in the house. My voice was shaking, my hands were shaking and my legs were shaking,” Paczynski recalled. “His wife led me to the first floor and into a bathroom. There was a mirror and a chair and within a moment Hoess arrived. He didn’t speak a word to me. But I said ‘bitte schoen’ to him and he sat down and I cut his hair.”

Hoess was apparently satisfied, having Paczynski return over and over though he never spoke a word of praise — or anything at all.

Paczynski was in Auschwitz until Jan. 18, 1945, when the Nazis moved the prisoners out, days before the Soviet army liberated the camp. He was later freed by U.S. soldiers in Germany.

Paczynski said he never witnessed any brutality by Hoess, who developed and oversaw the implementation of gas chambers where over a million Jews and others were murdered.

From what Paczynski observed, Hoess appeared to be “an ideal father and an ideal husband.”

“He was a man of very few words,” Paczynski said. “And he would never actually hit a prisoner.”

Hoess was tried by Polish authorities after the war and was sentenced to death by hanging in 1947. The sentence was carried out at Auschwitz next to a crematorium.

(AP)