By Rabbi Yair Hoffman for 5tjt.com

Recently, a Facebook post contrasted “Security Cameras” from the 1960’s to the contemporary security cameras in a rather humorous manner. There is another contrast, however, that can be made as well. The contemporary security cameras (above right) also have a number of halachic hurdles to overcome. The 1960’s security cameras (above left) do not [at least as far as Shabbos goes].

In many locations, the need for security cameras is, indeed, great. What follows is a discussion of the possible underlying issues. Of course, each person should consult with his own Rav or Posaik as to the exact guidelines of whether it is permitted to install such a device, and whether it is permitted to walk by one.

THE TWO MAIN ISSUES

There are essentially two main issues when it comes to security cameras. Both of these issues come up when one decides to install a security camera that will be functioning over Shabbos, and when one walks by a security camera on Shabbos.

The issues are:

- Causing extra electricity to be used by the people walking before the camera.

- Kesiva – writing, (believe it or not.)

It should be noted that many good security cameras come with a motion detection feature which causes extra electricity to be used when one walks by. The Wyze Cam Pan, for example, is a very popular model that does this. This is also true with the Ring Spotlight Cam. The Google Nest Cam IQ does the same thing. If you are unsure whether your model does this, you can use the Kill a Watt gadget to determine this. Long ago, a friend of mine did these experiments recording different colors and reported that the brightness of the subject also caused variations in the amount of electricity that was used. Some camera systems also have sound recorded and that too causes an increase in electric activity.

There are three opinions as to how electricity is viewed in halacha:

- Group A poskim hold that electricity involves a biblical prohibition of one sort or another.

- Group B poskim hold that electricity involves only a Rabbinic prohibition of Molid.

- Group C poskim hold that electricity involves a prohibition of Uvdah d’Chol.

It is important to know the different levels of prohibition involved in order to determine what exactly may be permitted for what particular reason. For example, the security cameras that exist in the old city within a certain perimeter around the Kosel – were permitted by Rav Elyashiv zt”l because of the very high threat level involved.

Another concept that we must become aware of is the notion of Grama – an indirect cause.

- Direct Action – generally a Biblical prohibition.

- Grama – generally a Rabbinic violation.

- Semi-Grama – also known as not considered a Grama and thus fully permitted.

Grama means a “causation force” rather than a “direct force.” The laws of grama on Shabbos are derived from the Talmudic passages of grama in damages and in murder. Not that “causation force” is permitted, necessarily. At times it is forbidden by Rabbinic decree. The Shulchan Aruch and Ramah (OC 334:22) rules that a grama is forbidden on Shabbos except in cases of loss or great need.

GROUP A POSKIM

The first Posaik to hold that electricity involves a Torah prohibition is the author of the Mishpetai Uziel, Ben Tzion Meir Chai Uziel zt”l (1880- September 4, 1953). He writes (Mishpetai Uziel Volume I in the Hashmatos siman 2) that the use of electricity involves the Torah prohibition of Makeh b’Patish. Contrary to what we all learned in elementary school, according to the Rambam, this malacha is violated at any stage of the preparation of the vessel. Rav Isser Zalman Meltzer in his Even HaAzel (Shabbos 10:17) understands the prohibition of Makeh b’Patish as a general category that involves anything that is done to make a kli perform. Rav Asher Weiss shlita expounded this same halachic view when he spoke at the White Shul in Far Rockaway a number of years ago.

There is a seminary – that is designed for young women coming out of public school. They do not have the resources that others have. Please donate whatever you can to the link below.

https://thechesedfund.com/simastuition/fundraiser

The more famous Group A opinion is that of Rav Avrohom Yeshayahu Karelitz zt”l (1878- October 24, 1953), , author of the Chazon Ish (OC 50:9). He writes (both in his commentary and in his subsequent letters to Rav Shlomo Zalman Auerbach zt”l) that electricity is a violation of Boneh – building – for two different reasons:

- Connecting the two formerly disconnected wires involves the creation of a circuit and one complete unit. This is no different than taking formerly disconnect parts of a vessel and connecting them which the majority of Rishonim hold is a Torah prohibition.

- Allowing for the flow of electrons through a circuit is a violation of “nesinas tzurah lehigashem” – placing shape into physical form. This is like awakening the wires from “death to life” – which is a violation of Boneh according to the view of the Ramban.

The shutting off of the circuit also involves the prohibition of sosair – breaking.

The way motion detecting cameras work is the opening and closing of secondary side circuits which would be a violation of a Torah prohibition according to the Group A Poskim. The difference between the two views may be as to whether the shutting off of the secondary circuitry would involve a prohibition according to the Mishpetai Uziel and Rav Asher Weiss, as there is no “opposite Malacha for Makeh b’Patish (although it is possible that the shutting off is a form of Makeh b’Patish too).

There are also some prominent Poskim that have taken the view that since, according to the Yerushalmi in Shabbos (7:2) there are a total of 1521 varying Torah prohibitions on Shabbos (called tolados), it is veritably impossible that such a far-reaching concept of electricity is not a violation of one of them. [If we add to this the original 39 malachos – we get 1560]. We thus have three different opinions as to what exactly is the Torah prohibition involved in the use of electricity.

It is important to note, however, that the use of the extra use of the electricity often involves an indirect action known as a “grama.” That may make the violation significantly less rigorous according to the Group A Poskim. According to this view, we would need to further understand the parameters of a grama.

The most famous view disagreeing with the Group A Poskim is that of Rav Shlomo Zalman Auerbach zt”l (1910-1995) in his Minchas Shlomo (Vol. I #9). What prompted his analysis of the issues was the fact that, at the time, hearing aid batteries needed to be changed more often than they do nowadays – and his own mother had times when the battery died on Shabbos. The action involved in changing it allowed the electricity issue to be heard.

GROUP B POSKIM

The second view of electricity being a Rabbinic violation of Molid was first espoused by Rav Yitzchok Yehudah Shmelkes (1828-1906) in his Bais Yitzchok YD Vol. II #31). His argument is that just as there is a Rabbinic prohibition of introducing a nice fragrance into clothing – there is, certainly, a likewise prohibition of inserting electricity into a circuit. We find the idea of Molid in three other places in Shas – Molid aish -fire (See Taz OC 502:1); Molid mayim – water from snow (Shabbos 51b according to Rashi), and Molid Kol- sound (Eiruvin 104a according to the Vilna Gaon and Rabbeinu Chananel). Interestingly enough, this seems to be a debate between the Ramah and the Mechaber as to how to understand it exactly (See Shulchan Aruch OC simanim 338 and 339).

GROUP C POSKIM

The notion of Uvdah d’Chol is considered to be less of a violation, then an out and out Rabbinic prohibition and is, at times, permitted by Poskim when there is a strong Dvar Mitzvah involved. This is only when it stands alone, however. Uvdah d’chol is not permitted for a Dvar Mitzvah when there is any srach melacha involved.

This is the clear ruling of the Pri Magadim in his Aishel Avrohom 306:16. Although one could possibly argue that this Pri Magadim is only for Ashkenazim (although we do not find any Sefardic authority that argues). There is a clear proof from the Gemorah in Shabbos 143b proving the Pri Magadim. The Gemorah there states :uBilvad shelo yisfog” – yisfog is an example of uvdah dechol and it is not permitted for the tzorech Mitzvah of the classic example of saving the three meals for Shabbos.

ISSUE #2: WRITING

The second issue is that these security cameras may involve a prohibition of writing. Rav Moshe Feinstein zt”l had addressed a similar issue in regard to closed circuit television in a letter dated February 7th, 1982 to Rabbi Yisroel Rosen a”h (1941-2017), the former director of the Tzomet Institute written by Rav Moshe’s grandson, Rabbi M. Tendler. [Three days later, Rav Feinstein affirmed that this was in fact his opinion]. His ruling that since the writing is not of a permanent nature, it is just an issur derabanan at best. He further stated that one who passes by is only performing a Psik Raisha that he does not care about – it would be permitted to pass by. This letter is reprinted in Tchumim Vol. XIV p. 433.

Rabbi Rosen posed the question again to Rabbi Yehoshua Neuwirth zt”l (1927-2013), author of the Shmiras Shabbos K’hilchasa on December 5th of 1990 and informed him of Rav Feinstein’s ruling. He questioned whether it is, indeed, to be considered a Psik Raisha that one does not care about. Rav Neuwith responded (the date in the letter is incorrect) 1] Who is he to question Rav Feinstein – especially since it is true that it is not a permamnet writing and 2] who ever said that this is considered writing? 3] He discussed the issue with Rav Shlomo Zalman Auerbach who said that there is no concern and that it is not writing. And 4] He expressed that it may use extra electricity.

He did not address the issue as to whether it is a psik raisha that he cares about.

Rav Elyashiv zt”l and others held that digital writing is definitely a forbidden act. This can be seen from the letter signed below. Rav Herschel Schachter shlita, in a conversation with this author, also held that digital writing certainly can be considered a derbanan for of writing.

OTHER HALACHIC ISSUES

There are also a number of other halachic issues that need to be taken into account. Firstly, we know that there is a debate in regard to a Psik Raisha that one does not care about regarding a derabanan. The Aruch holds that it is permitted while Tosfos (Sabbos 103a) holds that it is forbidden.

Secondly, we need to know what is a grama or a semi-grama and where the definitional differences lie.

What are the halachic factors that would make something that is causative a semi-Grama rather than a Grama?

There are three main approaches in the Poskim:

- Some Poskim hold that if there is a delay in time between the person’s action and the result then it would be considered a semi-Grama.

- Other Poskim hold that if the secondary action will not perforce occur then the causative action is not even considered a grama. In other words if it is not definite that the secondary result will happen – it would be considered a semi-Grama, not a Grama.

- Yet, other Poskim hold that if it is not the normal way in which this causative action is performed – then it is considered a semi-Grama.

Thirdly, we can also ask whether mere walking in front of a light or a camera is in fact forbidden. Rav Vosner in his Shaivet HaLevi (Volume IX #69) rules that it is just walking, and cannot be forbidden.

There is also the issue of a concern for Pikuach Nefesh. This may depend on where one lives as well. In the above article a number of issues were brought up and hopefully it will lead people to a greater understanding of what is involved. Each person, however, should ask his or her own Rav as to what is halachically advisable in their own situation.

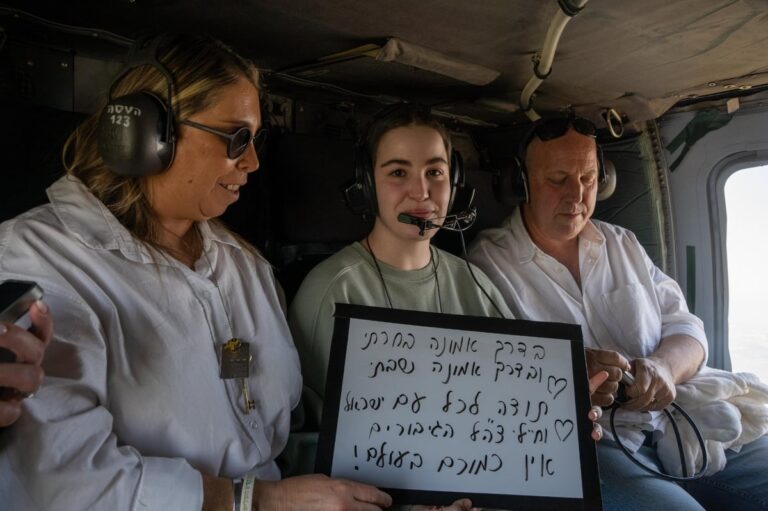

****Please do what you can for Sima, who has overcome adversity and has single-handedly created stability for her family. Now it’s time for her to invest in her Jewish growth.

Sima’s Story

Sima grew up in a non-observant home yet attended a local community day school in the New York area. Her father passed away several years ago and her fragile mother has had an increasingly difficult time coping. Sima alone has been responsible for maintaining a stable home for herself, her eight year old brother, and the baby from her mother’s most recent transient relationship.

Sima missed almost half of her senior year due to crushing household responsibilities, and has been unable to complete the necessary requirements to graduate from high school. Her community Rabbi, and biggest advocate, encouraged Sima to follow her dreams and attend a year in seminary to continue her growth in Yiddishkeit despite these burdensome obligations that overshadow her personal development. He has secured some minor scholarship funding for Sima, but it’s not enough to cover her expenses for the year.

https://thechesedfund.com/simastuition/fundraiser

The author can be reached at [email protected]