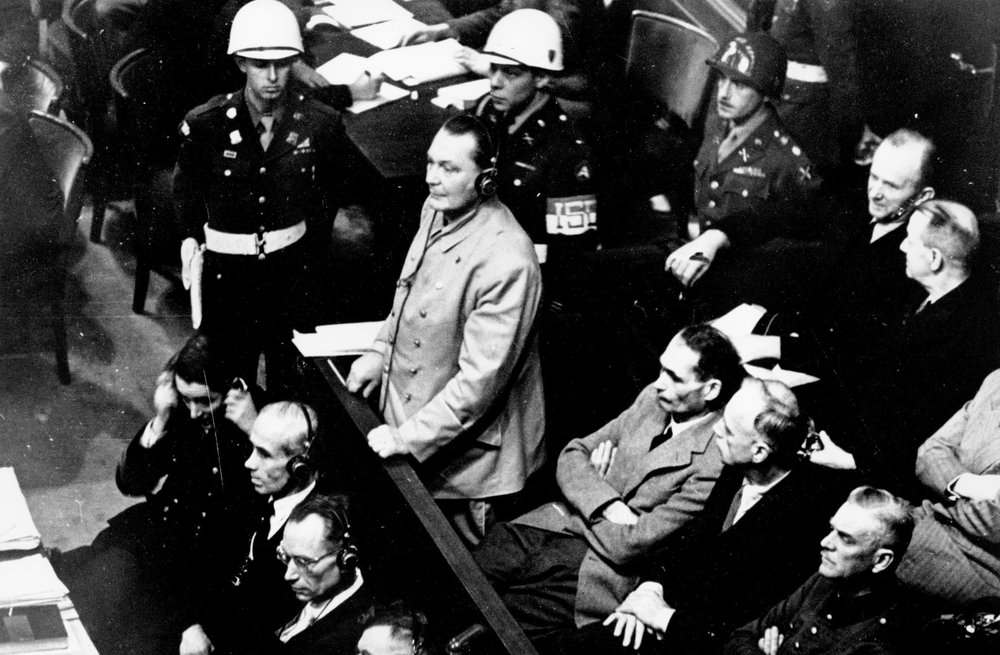

Seventy-five years ago, the dock of Courtroom 600 of the Nuremberg Palace of Justice was packed with some of the most nefarious figures of the 20th Century: Hermann Goering, Rudolf Hess, Joachim von Ribbentrop and 18 other high-ranking Nazis.

They weren’t yet known as war criminals — it was a charge that didn’t exist until the Nuremberg trials began on Nov. 20, 1945, in what is now seen as the birthplace of a new era of international law.

The proceedings broke new ground in holding government leaders individually responsible for their aggression and slaughter of millions of innocents. In addition to establishing the offense of war crimes, it also produced the charges of crimes against peace, waging a war of aggression, and crimes against humanity, whose legacies live on in the International Criminal Court of today.

Nuremberg was the city where Adolf Hitler reviewed torchlight Nazi party rallies and promulgated the race laws of 1935 that paved the way for the Holocaust.

Filmmaker Leni Riefenstahl’s famous propaganda movie “Triumph of the Will,” with its sweeping aerial photography and other pioneering techniques, brought the 1934 Nuremberg Nazi Party Congress to the world, with footage of top officials speaking to massive crowds of followers at the Bavarian city’s Luitpold Arena and the sweeping Zeppelin Field. The Congress Hall begun by the Nazis near the parade grounds was never finished, and today houses a documentation center about Nuremberg’s history during the Nazi era.

The choice to use the city’s Palace of Justice for the trials was less symbolic than pragmatic, as it was one of the few large buildings left undamaged by Allied bombing during the war.

The testimony of hundreds of witnesses was heard over 218 trial days. One of them was Rudolf Hoess, the Auschwitz death camp commandant, who “reacted to the order to slaughter human beings as he would have to an order to fell trees,” wrote U.S. prosecutor Whitney R. Harris.

Chief U.S. prosecutor Robert Jackson and his colleagues also had the Nazis’ own meticulous records to work from, quoting document after document in “laying bare the workings of the German conspiracy,” Associated Press correspondent Daniel De Luce reported from the courtroom at the time.

On Oct. 1, 1946, Goering, Hitler’s air force chief and right-hand man, was sentenced to death along with 11 others, including Martin Bormann, Hitler’s deputy, who was tried in absentia. Bormann is now known to have died in Berlin in 1945 as he tried to flee the Soviets. Seven drew long prison sentences and three were acquitted.

Fifteen days later, the condemned men were hanged in the courthouse’s adjacent prison. Goering committed suicide by swallowing a poison pill in his cell the night before.

One of the last surviving witnesses to the trial, Emilio DiPalma, died earlier this year after contracting the coronavirus in the care home where he lived in Massachusetts.

After fighting the Germans on the front lines during the war, DiPalma found himself at age 19 being tasked to serve as a guard in the courtroom, where he stood at the witness box with his arms clasped behind his back while Hitler’s deputies were grilled about their atrocities.

“To this day, I can hardly believe that any human being could do such cruel things to another,” DiPalma wrote in his memoirs.

The city of Nuremberg marked the anniversary in Courtroom 600 with a ceremony Friday that will include German President Frank-Walter Steinmeier as the guest of honor. Due to coronavirus restrictions it was closed to the public, but was broadcast live on the internet including an English translation.

(AP)