News from the frontlines of eastern Ukraine’s five-year-old frozen war has long slipped from Western headlines, but for the people living in the region, daily reminders of the conflict’s existence abound. On the outskirts of Donetsk, a city of just under a million residents, the sounds of fighting—even the occasional mortar—can be heard, and though less frequent and nowhere near the ferocity it once was, it’s still there. Another reminder is the nightly military curfew, imposed by the government of the self-declared Donetsk People’s Republic, requiring all individuals to be off the streets between 11 p.m. and 5 a.m.

This presents a curious dilemma for the Jewish community of Donetsk, which prior to hostilities numbered about 15,000 people and stands today at about 3,000: How to gather for a public Passover seder, traditionally a long affair, when young and old must be in by 11?

“Before the war, our Passover seder in the synagogue would end at 1 or 2 a.m.,” says Misha Katz, 41, a Donetsk native who lives in the city with his young family. “Now, we’ll just have to do it quicker.”

Passover begins this year on Friday night, April 19, about a month later than usual, and since the seder can only begin after nightfall (around 8 p.m. in Donetsk), it will have to be short indeed, ending with enough time for the 80 or so expected participants to be back in their homes on time. Yet Katz says the Jews of Donetsk won’t be deterred.

“We’ll have matzah and wine, and our children will ask the Four Questions,” says Katz. “With G‑d’s help, we will have a joyous seder, like real Jews.”

The procurement of Passover foods, but especially matzah—a touchstone of Jewish identity in the region since the Soviet era—is not as simple in Donetsk and the wider eastern Ukraine region as it once was. Two years ago, in 2017, the matzah arrived just a few days before Passover.

“In a way, it does remind me of what we went through in Soviet times,” Katz says of the yearly matzah predicament. “My grandparents baked matzah at home, but somehow they always had it. It’s the same for us here; we always end up getting it.”

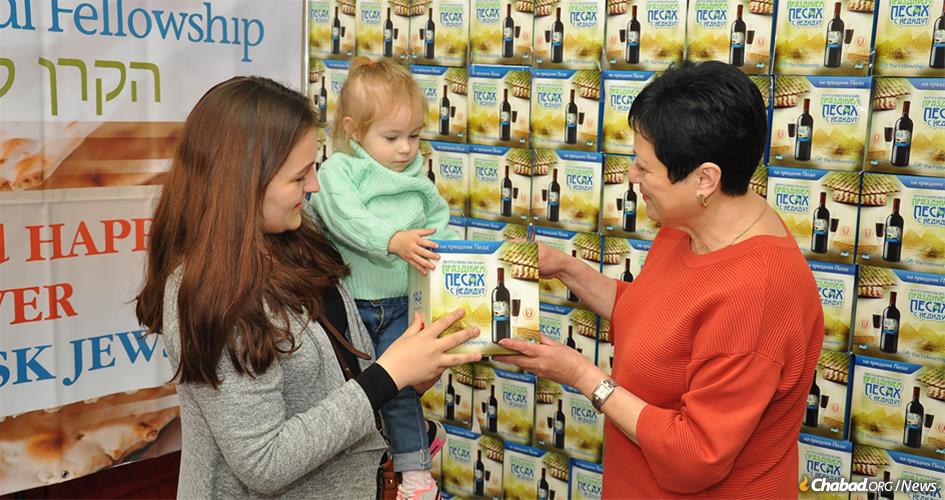

This year, the community’s longtime leader, Rabbi Pinchas Vishedski, co-director of Chabad-Lubavitch of Donetsk, has already arranged the shipment of three tons of matzah to the city, along with thousands of aid packages, including Passover essentials such as wine, oil and a freshly printed Russian-language Haggadah. Vishedsky and his wife, Dina, are now based out of Ukraine’s capital city of Kiev, where they direct both a Jewish center for refugees from eastern Ukraine, as well as their center in Donetsk.

“We are surviving here because of the unending help of our rabbi and Dina,” says Katz. “They think of the things we need, and all of the things we didn’t even think of.”

Most of the Donetsk seder participants will be those who live closer to the synagogue in the city center, while those further out, including in the surrounding towns, will be using their Passover aid packages.

The matzah and aid that recently arrived and was distributed in Donetsk is sponsored by the International Fellowship for Christians and Jews and the Federation of Jewish Communities of the CIS (FJC), the umbrella group for Jewish communities throughout the former Soviet Union.

The Fellowship, which has long been an important source of support for Jewish communities in the former Soviet Union—and maintains projects around the world—was until recently headed by the Rabbi Yechiel Eckstein, whose sudden passing in February shocked his many admirers around the world. It is now being led by his daugher, Yael Eckstein, and all of this year’s Passover aid is in Rabbi Eckstein’s memory.

“We were only able to realize this massive project with the help of the Fellowship and Yael Eckstein,” attests Vishedski. “Help for the Jews living in Donetsk and the entire region is critical throughout the year, but especially now, before Passover.”

While once upon a time, Vishedski would have been concerning himself with preparing for Passover only in the Donetsk region, where he and his wife first arrived in 1993, he now has a second community in Kiev.

“Those who are refugees left so much of their lives behind in the east, and they still need much assistance,” he says. “We have distributed, also with the help of the Fellowship and the FJC, 3,000 food packages here, which aside from matzah and Passover goods also include items such as chicken.”

In Kiev, he will also lead two massive public seders for his community in exile. Separately, a Passover retreat for 100 young families and students has been organized, allowing the young people to experience the holiday in an all-inclusive family-style setting.

But those in Kiev are constantly apprehensive for their family and friends back in Donetsk, their relatives or elderly parents still living for whatever reason in the territory, and so the aid sent to the Jewish community there has a doubly comforting effect on those in Kiev.

“People worry that those in Donetsk should have all their holiday needs there,” adds Vishedski. “For the Jews with us in Kiev, knowing that the community cares for those in the war zone allows them to be calm and happy and celebrate wholeheartedly here as well, knowing there is matzah and delicious food on the other side as well.”

In Donetsk, Katz says their Jewish community is having a difficult time without their rabbi and his wife on site, but they understand that it needs to be this way, if only for the support that continues to arrive.

“There are Jews in Donetsk—a lot of them—and people should know that we’re here,” says Katz. “With everyone’s continued help, we are making the absolute best of the situation.”

Click here to assist the Jewish Community of Donetsk.

(Source: Chabad.org)

One Response

so beautiful!

yasher koach!