Lawmakers are working on a set of new and unprecedented Iran sanctions that could prevent the Islamic republic from doing business with most of the world until it agrees to international constraints on its nuclear program, officials say.

Lawmakers are working on a set of new and unprecedented Iran sanctions that could prevent the Islamic republic from doing business with most of the world until it agrees to international constraints on its nuclear program, officials say.

The bipartisan financial and trade restrictions amount to a “complete sanctions regime” against Tehran, according to one congressional aide involved in the process. But it could put the Obama administration in a difficult position with allies who are still trading with Iran, but whom the U.S. needs if it is to secure a peaceful solution to the Iranian nuclear standoff.

On Thursday, in its first foreign policy announcement since the president’s re-election, the administration targeted four Iranian officials and five organizations with sanctions for jamming satellite broadcasts and blocking Internet access for Iranian citizens.

But the measures that Sen. Mark Kirk, R-Ill., and Sen. Robert Menendez, D-N.J., want to attach to a defense bill would be far more sweeping. They would target everything from Iranian assets overseas to all foreign goods that the country imports, building on the tough sanctions package against Tehran’s oil industry that the two lawmakers pushed through earlier this year, congressional aides and people involved in the process said. Those earlier measures already have cut Iran’s petroleum exports in half and hobbled its economy.

Yet even as the value of its currency has dropped precipitously against the dollar in a year, sparking an economic depression and massive public discontent, Iran’s leadership has yet to bite on an offer from world powers for an easing of sanctions in exchange for several compromises over its nuclear program. To break the logjam, the administration is brainstorming ways to make the offer more attractive for the Iranians without granting any new concessions that would reward the regime for its intransigence, according to administration officials who spoke on condition of anonymity because they weren’t authorized to speak publicly on the matter.

Escalating the sanctions, the measure’s supporters say, could accelerate the point to which the Iranian economy is bankrupt, forcing Ayatollah Ali Khamenei to give ground in the nuclear negotiations. Supporters say they hope Iran’s oil-inflated foreign currency reserves are depleted before it has the capacity to produce nuclear weapons-grade material, which Israel and others say could be as soon as August 2013.

The United States and other world powers have been trying to gauge whether a negotiated solution is possible with Iran. Washington and many of its European and Arab partners fear Iran is trying to develop nuclear warheads, even if Iran insists that the program is solely designed for peaceful energy and medical research purposes. The Obama administration says military options should only be a last resort and has pressed Israel to hold off on any plans for a pre-emptive strike against Iran’s nuclear facilities.

But tensions between the U.S. and Iran remain high, a fact underlined by the Pentagon’s revelation Thursday that an Iranian military plane fired on, but missed, an unarmed U.S. drone aircraft a week ago. The incident occurred in international airspace over the Persian Gulf, Pentagon spokesman George Little said.

Despite no progress in the nuclear talks, administration officials say the contours of any diplomatic solution are clear: U.S., European and other international sanctions would be eased if Iran halts its enrichment of uranium that is getting closer to weapons-grade, ships out its existing stockpile of such uranium and suspends operations at its underground Fordo facility.

The sanctions being considered by Kirk, Menendez and others represent the flip side to increased engagement but don’t necessarily work against the administration’s effort. They could, in fact, be an effective threat of even worse economic pressure to come that Obama’s negotiators can use against Tehran.

Whereas last year’s sanctions went after oil exports, Iran’s primary source of revenue, the new approach focuses on the agricultural, industrial and consumer goods the country imports to ensure manufacturing capacity and the basic functioning of its economy, the congressional aides and others involved said.

Companies from Europe, Asia and elsewhere selling machinery and other products to Iran would have to stop or face being cut off from the U.S. market. Banks whose clients are making transactions with Iran would face a similar penalty if they don’t break off relations. And Iranian assets in financial institutions overseas would have to be frozen.

There would be exemptions. The plan envisioned by Kirk and other senators wouldn’t affect food, medicine and democracy-promotion goods such as communications equipment, officials said. The 20 countries that have been granted exemptions by the Obama administration to purchase decreasing levels of petroleum from Iran would be permitted to continue doing so.

Kirk prefers providing no new waiver authority for the administration that might allow Germany, for example, to continue selling machine tools or China to continue exporting cheap merchandise to Iran as long as they make significant reductions in the total value of their transactions. The administration likely would demand such flexibility so it can persuade its international partners to get on board, as it did with the petroleum sanctions. Menendez and others in the Senate are considering how to provide them that flexibility, people familiar with the different plans said.

Congress has overwhelmingly backed previous efforts by Kirk and Menendez, but the fate of the Senate’s defense policy bill is uncertain.

Democrats and Republicans have pressed for the Senate to take it up in the lame-duck session that begins Tuesday, but Majority Leader Harry Reid, D-Nev., wants both sides to agree on limiting the number of amendments, which could exceed 100. It’s unclear whether the two parties can reach agreement. As an alternative, the Senate may simply vote on a pared-back, noncontroversial bill that has been worked out in advance with the House.

Mark Dubowitz, a sanctions expert and executive director of the Foundation for Defense of Democracies, described the wider economic offensive against Iran as much-needed. Existing sanctions have done damage but Iran still has enough in reserves to remain solvent until mid-2014, well after Tehran could cross the “red line” of nuclear progress as outlined by Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu and embraced by some in Congress.

Even if Iran’s petroleum exports have declined to 1 million barrels a day from last year’s level of 2.5 million barrels a day, Dubowitz said, the government would pull in $37 billion in revenue next year — assuming a market rate of about $100 a barrel. “We’re still a long way from an economic cripple date,” he cautioned.

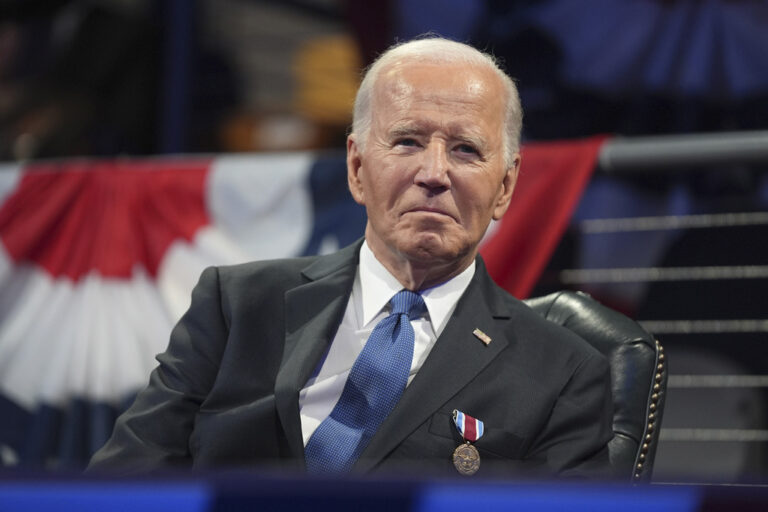

(AP)