By Rabbi Yair Hoffman for the Five Towns Jewish Times

It was the young lady’s third date. Her date had taken her to a restaurant to eat out. The conversation went well and he seemed to be a super guy. Shockingly, he did not leave a tip. To quote my seventh-grade daughter: “Awkward.”

Aside from the question of what the young lady should do, another question arises. Is there a halachic obligation to leave the waiter a tip? What about tipping a taxi driver? Or an Uber driver? What is the halacha?

The author’s books can be purchased at amazon.com.

HISTORY OF TIPPING

From a historical perspective, tipping began as an aristocratic practice in England and then among the upper classes of Europe. After the Civil War in the United States, wealthy Americans started visiting Europe in record numbers and brought back the custom to the United States to show off their worldliness. The New York Times in 1897 described the spread of tipping like “evil insects and weeds.” In 1916, William Scott wrote an entire tract against tipping and called it the “Itching Palm.” There he writes, “Tipping, and the aristocratic idea it exemplifies, is what we left Europe to escape.”

Since then, however, tipping has become nearly universal in this country. This has some halachic repercussions. In less than a century, there may have developed a halachic obligation to tip based upon the near universality of the custom.

THE HALACHA

Generally speaking, the halachah is that payments agreed to in a transaction are what is binding. If no additional payments were agreed to, neither in writing nor orally, there is no obligation to pay it. However, the Rashba in a responsum (Volume II #168) writes that a minhag negates the halachah even in regard to monetary matters. This is true even if the issue was not specifically discussed either in written or oral communications prior to the contract. This is also the position of the Rivash (responsa nos. 171 and 474) and others as well. Indeed, local custom even in contracts is normative halachah. It is this author’s view that in the United States, the custom has already developed to tip a taxi driver, but the custom has not (yet) developed to tip an Uber driver.

This is noteworthy because Uber drivers in New York City have gotten together and have formed a group called the Independent Drivers Guild. On April 17, this group successfully petitioned the New York City Taxi and Limousine Commission to create a rule that would require ride-hailing services such as Uber to add tipping capability into their phone apps. According to an article in USA Today, Uber has argued “since its inception that not allowing in-app tipping was one of the things its riders liked best about it.” All this is proof that the custom to tip Uber drivers has not yet entered a state anywhere near of that which regular taxis receive tips.

The founder of the Independent Drivers Guild, Jim Conigliaro Jr., has said, “New York City’s professional drivers have traditionally depended on gratuities for a substantial portion of their income. Cuts to driver pay across the ride-hail industry has made tipping income more important than ever.”

Uber’s major competitor, Lyft, has been attracting Uber drivers to come to their company because their app allows for tipping. This, too, is proof that tipping an Uber driver has not developed into the universal custom that the Rashba refers to.

Regarding tipping taxi drivers, the Debreciner Rav, z’l, Rav Moshe Stern, writes in Be’er Moshe (Vol. III #117) that if a chassidic-looking individual doesn’t tip the taxi driver, it will cause them to avoid chassidic-looking people. He does not deal with the issue of universal custom, which would indicate either that he does not hold that it has become a universal custom in the United States or that he disagrees with the underlying application of the idea. But the fact that he writes that the taxi drivers would not come indicates that the concept of tipping has become universal.

MODERN POSKIM

The author of Ein Lamo Michshal (Vol. IX 16:8) writes that not tipping in a restaurant involves a “chashash issur gezel—a concern for the prohibition of theft.”

However, that author’s brother-in-law takes issue with this position (see Asher Chanan Vol. VII # 151) and writes that the former’s position may be a chashash issur gezel on the rabbi’s part for writing that there is an obligation to tip! Not to get into a possible family squabble here, it would seem that the real issue is how evolved the custom has become.

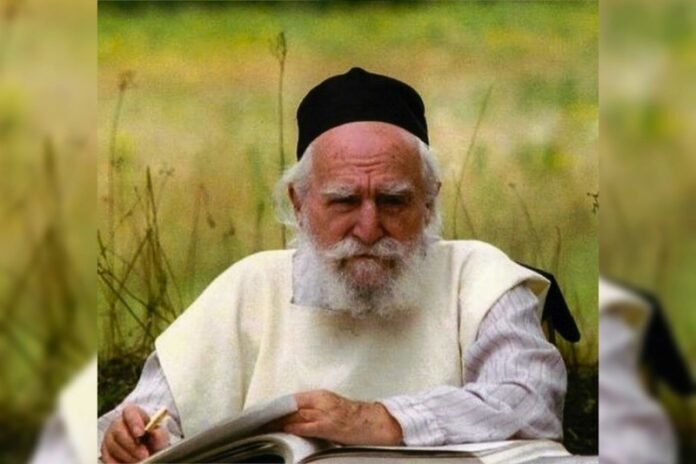

RAV ELYASHIV’S POSITION

In the Tammuz 5760 edition of the Mevakshei Torah Journal, Rav Elyashiv, zt’l, is quoted as saying that it is ch’shash gezel- there is a concern for theft if one does not tip at a restaurant (or at a wedding hall—where apparently the minhag has developed to customarily tip). He is quoted as saying that one must give a minimal tip.

Lest the reader think that this is merely a quote of Rav Elyashiv in a journal, Rav Elyashiv’s son-in-law, Rav Yitzchok Zilberstein, shlita, writes (Tuvcha Yabiu Vol. II page 107) that this was Rav Elyashiv’s view.

It should be noted that in Israel there is no minhag to tip taxi drivers, as opposed to here in the United States.

A POSSIBLE EXPLANATION FOR THE DEBRECINER RAV

A possible explanation of the Debreciner Rav z”l, who seems to have held that it is near universal to tip, but still did not consider it ch’shash gezel – possible theft is as follows: The person taking the job (whether a waiter or a taxi driver) knew that there is a tiny small minority of people that do not tip. They took the job or fare with this contingency in mind. Therefore, it may not necessarily be gezel – theft (Thank you B. Bodner for the explanation.)

HALACHIC CONCLUSION

To this author, it would seem that regarding taxis in the United States, there is a halachic obligation to tip. For taxis in Israel, there is no obligation. For Uber drivers, there is no obligation to tip as yet. Regarding waiters and waitresses in the United States, there would be an obligation. According to the author of Asher Chanan, however, matters have not reached the state where there would be any concern of halachic theft. As in all matters of halachah, one should consult his or her own rav or posek.

WHAT THE YOUNG LADY SHOULD DO..

Now let’s get back to the awkward position of the young lady on the date. Saying something might cause the guy to feel bad, and she might violate the prohibition of ona’as devarim. However, there is also the issue of the other’s halachic obligation. It would seem that she should delicately bring up the idea as a halachic discussion. If this is uncomfortable, she could feasibly rely on the poskim that permit not leaving the tip—especially if the issue was not mentioned by the Debreciner Rav in his responsum on taxis. v

The author can be reached at [email protected].

One Response

If it bothers her , SHE should leave a tip.

He would get the message and her conscience would be clear.