by Rabbi Yair Hoffman

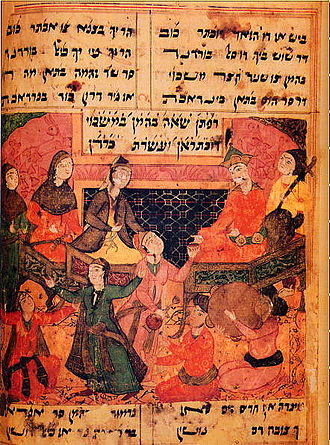

There is an oustanding Rabbinic figure in Persian Jewish history that is not so well known outside of the Persian Jewish community, but he stands as the earliest and most accomplished commentators and poets in Jewish Persian history. Mulana Shahini Shirazi lived during the time of the late Rishonim and was one of Persian Jewry’s greatest commentators – fully fluent in Shas, Yerushalmi, and the various Targumim.

His writing showed intimate mastery of the major midrashic works, including Bereishis Rabbah, Shemos Rabbah, Vayikra Rabbah, Midrash Tanchuma and Midrashim that are no longer extant. He incorporated insights from Pirkei D’Rabbi Eliezer and clearly also consulted Saadia Gaon’s groundbreaking Arabic translation of the Torah. His name, which translates to “Our Master, the Royal Falcon of Shiraz,” reflects his prominent status in Persian-Jewish literature.

The title Mullah according to Persian-Jewish tradition stands for the Roshei Teivot of Mi Lashem Ailai indicating their dedication to Torah-true Judaism.

Shahin and Hafiz

Shahin lived during Sultan Abu Sa’id’s reign (1316-1335), yet much of his life remains shrouded in mystery. He lived in Shiraz around the same time as the famous Persian poet Hafiz.

Shams-ud-din Muhammad Hafiz (c. 1320-1389) was one of the most renowned and beloved poets in Persian literature. He is widely regarded as one of the seven literary wonders of the world, a view shared by eminent figures such as Ralph Waldo Emerson and Johann Wolfgang von Goethe.

Emerson, the celebrated American philosopher and poet, was particularly effusive in his praise of Hafiz. He famously said of Hafiz, “He fears nothing. He sees too far, he sees throughout; such is the only man I wish to see or be.” Emerson even went so far as to bestow upon Hafiz the grand compliment of calling him “a poet for poets.”

Persian Jews who are familiar with the works of both of them say that Shahin was even a greater poet than Hafiz

Scholars remain uncertain about Shahin’s birth, death, and general occupation. Sources also disagree about his origins, with some claiming he was buried in Shiraz, while others suggest he came from Kashan.

The Major Works and Their Structure

Shahin created two main collections of epic poetry that transformed biblical narratives into Persian poetic verse. His first collection included masterful versions of Bereishis, Iyov, and extensive sections about Moshe Rabbeinu. The second collection wove together the stories of Ardashir, Esther, and Ezra into a complex narrative tapestry.

The Moshe Rabbeinu narrative, composed first in 1327, demonstrated his early mastery of the craft as he rendered Midrashim from Shemos, Vayikra, Bamidbar, and Devarim into Persian verse.

For this work, he chose the hazaj musaddas makbūd meter, a Persian poetry style that was commonly used in Persian literature. This extensive work contained approximately 10,000 verses. Later, in 1358, he composed his Bereishis work, a slightly shorter piece spanning 8,700 verses. These works sometimes appear in separate manuscripts, allowing them to circulate independently among different audiences.

Torah Narratives

In his Bereishis text, he included two particularly notable selections: a dramatic rendering of Satan’s fall from divine grace and a deeply moving account of Yaakov’s grief over losing Yosef. After completing his discussion of Eisav’s descendants, he added a fascinating 170-verse version of Iyov. In this condensed retelling, he made the striking choice to omit Iyov’s famous dialogues with his friends and Hashem’s extended response, focusing instead on the less-commonly emphasized story of Iyov’s wife’s challenges to his faith. This emphasis shows Shahin’s interest in exploring the human and domestic aspects of biblical stories. His choice to include Iyov’s story at this point in the narrative reflects Midrashic sources that placed Iyov within Yaakov’s extended family line, considering him either Eisav’s grandson or great-grandson.

The Esther-Ezra Epic

In 1333, between his Torah-based works, Shahin composed his masterful Ardashir-namah (AN), a 9,000-verse epic that employed a more complex poetic meter than his earlier works. This composition incorporated the traditional Megillah story with lost Midashim. It included elaborate narratives about Shiru, the son of Achashverosh and Vashti, adding a new dimension to the familiar narrative. Second, and perhaps creatively, he forged connections to Iran’s national epic, the Shah-namah, by ingeniously identifying Achashverosh with the character Ardashir. Third, he proposed based on Midrashim extant and lost that Koresh (Cyrus), the great Persian king who restored Jewish sovereignty, was actually the child of Esther and Achashverosh’s union, thereby linking Persian and Jewish royal lineages.

Original Scenes and Creative Elements

Shahin, based upon lost Midrashim, detailed accounts of Achashverosh’s search for a new queen following Vashti’s departure, explored Mordechai’s sophisticated role as a matchmaker, and described the royal wedding night with poetic sensitivity. The epilogue, called Ezra-namah (EN), though shorter at about 500 verses, carried significant theological weight as it focused on the rebuilding of the Beis Hamikdash and presented arguments against contemporary Muslim views regarding Ezra’s role in preserving the Torah.

Literary Style and Poetic Innovation

As a master of classical Persian poetic devices, Shahin wielded an impressive array of literary tools. He expertly employed tanasub to create harmony between concepts, used tazadd to develop meaningful contrasts, and crafted beautiful explanations through husn-i ta’lil. His use of ishtiqaq (paronomasia) demonstrated his sophisticated wordplay.

The poet developed a unique linguistic style that merged classical Persian structures with colloquial elements, notably in his distinctive use of -iman and -idan verb forms for first person plural expressions.

Compared to later Jewish-Persian poets, Shahin used Hebrew words more sparingly, yet he pioneered the combination of Hebrew and Persian words through the innovative -i (izafa) construction, setting a precedent for future Jewish-Persian writers.

Historical Impact and Cultural Significance

Iranian Jews embraced Shahin not merely as a poet but as an authoritative biblical commentator. The term tafsir, with its rich implications of explanation, commentary, and translation, aptly describes his contribution to Jewish-Persian literature.

Academic Study and Modern Understanding The most comprehensive academic treatment of Shahin’s work is known to be Wilhelm Bacher’s groundbreaking study, “Zwei judisch-persische Dichter Schahin und Imrani.” This pivotal work examines Shahin’s rhetoric, catalogues known manuscripts, and explores both Jewish and Muslim influences on his writing. However, scholars universally agree that more thorough study is needed across all aspects of his work. The complex interweaving of Persian and Jewish elements in his poetry, his innovative narrative techniques, and his influence on subsequent Jewish-Persian literature all merit deeper investigation.

Cultural Bridge and Literary Legacy

Perhaps Shahin’s greatest achievement was his role as a cultural bridge between Persian and Jewish traditions. His work demonstrated that these two rich cultural streams could be woven together without diminishing either. His epic retellings enriched both traditions, adding Persian literary sophistication to biblical narratives while introducing Jewish theological depth to Persian poetic forms. His influence extended well beyond his own time, establishing patterns of Jewish-Persian literary expression that would influence numerous writers for generations to come.

Published Works

His books in print, all edited by Shimon Hakham and published in Jerusalem by Y. Hasid Religious Books in 1995, include:

- Bereshit-namah Part 1

- Bereshit-namah Part 2

- Musa-namah Part 1

- Musa-namah Part 2

- Ardashir-namah

A significant portion of his work has akso been translated into Hebrew:

- Avner Peretz, “Shahin Torah – The Classical Persian-Jewish Epic from the Fourteenth Century” (Yeriot Publishing, 2010) – translating about one-fifth of “Musa-namah”

- Baruch Fikel, “The Song of Moses – A Complete Hebrew Translation of the Book of Musa-namah” (self-published, 2022)

Mullah Shahin Shirazi and his work is one of the jewels of Persian Jewry’s remarkable heritage. It is availble on the Otzer HaChochma and should be studied not only by Persian Jews, but by other students of Torah as well.

The author can be reached at [email protected]

One Response

In Judaism, when did Satan fall from divine grace? RABBI HOFFMAN RESPONDSl IT IS OUR GIRSAH OF THE BAHIR