Spurred by conspiracy theories about the 2020 presidential election, activists around the country are using laws that allow people to challenge a voter’s right to cast a ballot to contest the registrations of thousands of voters at a time.

In Iowa, Linn County Auditor Joel Miller had handled three voter challenges over the previous 15 years. He received 119 over just two days after Doug Frank, an Ohio educator who is touring the country spreading doubts about the 2020 election, swung through the state.

In Nassau County in northern Florida, two residents challenged the registrations of nearly 2,000 voters just six days before last month’s primary. In Georgia, activists are dropping off boxloads of challenges in the diverse and Democratic-leaning counties comprising the Atlanta metro area, including more than 35,000 in one county late last month.

Election officials say the vast majority of the challenges will be irrelevant because they contest the presence on voting rolls of people who already are in the process of being removed after they moved out of the region. Still, they create potentially hundreds of hours of extra work as the offices scramble to prepare for November’s election.

“They at best overburden election officials in the run-up to an election, and at worse they lead to people being removed from the rolls when they shouldn’t be,” said Sean Morales-Doyle of The Brennan Center for Justice, which has tracked an upswing in voter challenges.

The voter challenges come as activists who believe in the election lies of former President Donald Trump also have flooded election offices across the country with public records requests and threats of litigation, piling even more work on them as they ready for November.

“It’s time-consuming for us, because we have to consult with our county attorneys about what the proper response is going to be,” said Rachel Rodriguez, an elections supervisor in Dane County, Wisconsin, which includes Madison, the state capital.

She received duplicate emails demanding records about two weeks ago: “It’s taking up valuable time that we don’t necessarily have as election officials when we’re trying to prepare for a November election.”

Michael Henrici, the Democratic commissioner of elections in New York’s Otsego County, received a single-line email last week warning of unspecified “election integrity” litigation, then a follow-up complaining he hadn’t responded.

“These aren’t people with specific grievances,” Henrici said. “They’re getting a form letter from someone’s podcast and sometimes filling in the blanks.”

Multiple investigations and reviews, including one by Trump’s own Department of Justice, found no significant fraud i n the 2020 presidential election, and courts rejected dozens of lawsuits brought by Trump and his allies. But Trump has continued to insist that widespread fraud cost him re-election. That has inspired legions of activists to become do-it-yourself election sleuths around the country, challenging local voting officials at every turn.

In Linn County, Iowa, which includes the city of Cedar Rapids, Miller said he and the auditors who run elections in the state’s other 98 counties have been deluged with both records requests and voter challenges.

“The whole barrage came in a two-week period,” Miller said, following the tour by Frank, who uses mathematical projections to make claims of a vast conspiracy to steal the election from Trump, “and it’s happening to auditors across the state.”

Election offices routinely go through their voter rolls and remove those who have moved or died. Federal law constrains how quickly they can drop voters, and conservative activists have long complained that election officials do not move swiftly enough to clean up their rolls.

The recent challenges stem from activists comparing postal change-of-address and other databases to voter rolls. Election officials say this is redundant, because they already take the same steps.

Sometimes the challenges come after election conspiracists go door-to-door, often in heavily minority neighborhoods, seeking evidence that votes were cast improperly in 2020.

Texas’ heavily Democratic Harris County, which includes Houston, received nearly 5,000 challenges from a conservative group that went door-to-door checking voter addresses. The election office said it dismissed the challenges it legally had to review before the election and will finish the remainder after Nov. 8.

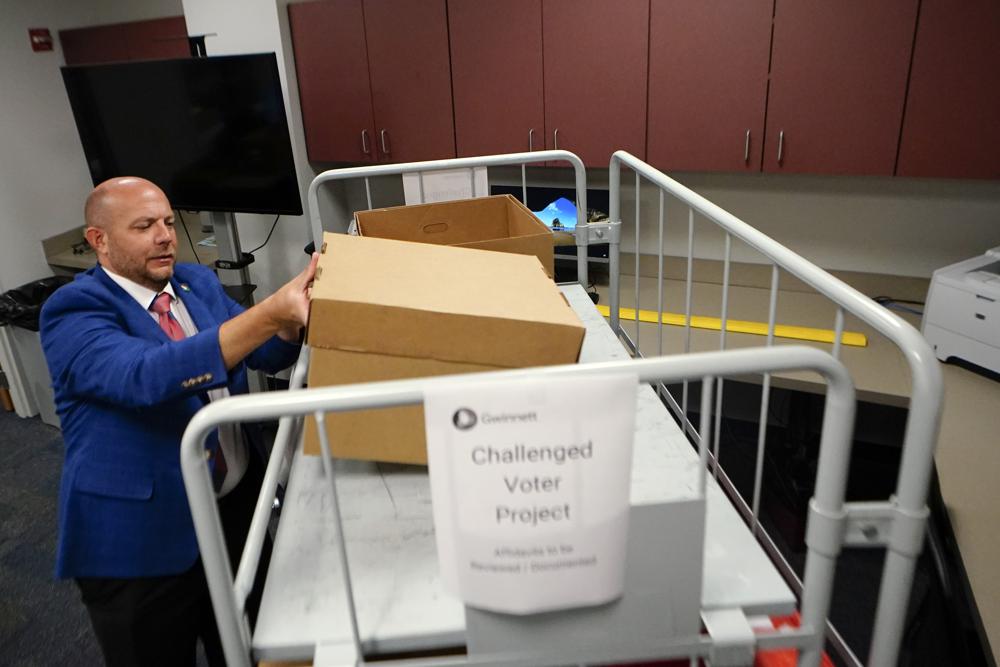

Activists in Gwinnett County, which stretches across the increasingly Democratic northern Atlanta suburbs, spent 10 months comparing change-of-address and other databases with the county’s voter rolls. They submitted eight boxes of challenges last month. About 15,000, they said, were complaints that specific voters improperly received mail ballots in 2020. Another 22,000 were for voters they contend are no longer at their registered address.

There are so many challenges that election officials have yet to even count them all. But Zach Manifold, Gwinnett’s election supervisor, said that, in every single mail ballot complaint the office has sampled, the voter properly received a mailed ballot.

But if any of the address-challenged voters do try to cast a ballot in November, the county’s elections board will need to decide whether that vote should count. They’ll only have six days to make a decision, as they have to certify their vote total by the Monday after Election Day under Georgia law.

Manifold estimated his office has a month to log and research the challenges, before mail ballots go out for the November elections: “It is a tight window to get everything done,” he said.

Many of the large counties facing voter roll challenges are places where President Joe Biden beat Trump in 2020, including Gwinnett and Harris. Yet those behind the effort dispute the notion that they are targeting Democratic-leaning counties and say they’re working on behalf of all voters. In Florida’s Nassau County, for example, Trump won with more than 72% of the vote.

“They should be glad that the voter rolls are being cleaned up so they can make sure their votes count,” said Garland Favorito, a conservative activist who has teamed up with supporters of Trump’s election lies and is helping with voter challenges in Georgia.

Favorito said more challenges are coming in other Georgia counties.

Under legislation passed last year by the Republican-controlled Legislature, there are no limits on the number of voter challenges that can be filed in Georgia. Most states implicitly set restraints on challenges, said Morales-Doyle of the Brennan Center. They require a complainant to have specific, personal information about the voters they target and establish penalties for making frivolous challenges.

Florida is an example. Its voter challenge law only permits the filing of challenges 30 days before an election, requiring election officials to contact each voter challenged before Election Day. It is a misdemeanor to file a “frivolous” challenge. But voter challenges almost derailed Florida’s primary last month in heavily-Republican Nassau County, in the northeastern part of the state.

Two women who belonged to a conservative group, County Citizens Defending Freedom, dropped off the nearly 2,000 challenges at the county elections office six days before the Aug. 23 primary.

Luckily for the office, the challenges were filed in an incorrect format. Elections Supervisor Janet Adkins told the activists they would review them, anyway — after the primary.

“To take away a person’s right to vote is a very serious thing,” Adkins said.

(AP)