When the coronavirus pandemic first hit the U.S., sales of window coverings at Halcyon Shades quickly went dark. So the suburban St. Louis business did what hundreds of other small manufacturers did: It pivoted to make protective supplies, with help from an $870,000 government grant.

But things haven’t worked out as planned. The company quit making face shields because it wasn’t profitable. It still hasn’t sold a single N95 mask because of struggles to get equipment, materials and regulatory approval.

“So far, it has been a net drain of funds and resources and energy,” Halcyon Shades owner Jim Schmersahl said.

Many companies that began producing personal protective equipment with patriotic optimism have scaled back, shut down or given up, according to an Associated Press analysis based on numerous interviews with manufacturers. Some already have sold equipment they bought with state government grants.

As COVID-19 was stressing hospitals and shuttering businesses in 2020, elected officials touted the need to boost U.S. production of protective gear: “All this stuff should be made in the United States and not in China,” Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis said in remarks echoed by others.

Yet many manufacturers who answered the call have faced logistical hurdles, regulatory rejections, slumping demand and fierce competition from foreign suppliers. On April 1, Florida-based American Surgical Mask Co. became one of the latest to close.

“I’m just done with the fight,” CEO Matt Brandman told the AP.

After the initial scramble for PPE subsided, many industry newcomers faced difficulty selling products. Government agencies sometimes wanted huge quantities at tough-to-meet deadlines. Hospital systems tended to contract with established suppliers. Retail sales waned after every virus surge.

“At the end of the day, when everybody said they wanted American-made, nobody’s buying, not even the state,” said Tony Blogumas, vice president of Green Resources Consulting, a rural Missouri firm that received an $800,000 state grant but has sold only a few thousand masks. “We’re kind of upset about the whole situation.”

Missouri Gov. Mike Parson also is disappointed. His administration divided $20 million in federal COVID-19 relief funds among 48 businesses for the production of masks, gowns, sanitizer and other supplies. Parson hoped to seed a permanent field of manufacturers.

“I’m still a firm believer in that — that we need to be making PPE here in this state,” Parson said. “Unfortunately, a lot of entities went right back to where they were getting it before.”

The onset of the pandemic revealed that the U.S. was highly dependent on foreign countries for protective gear. When China limited exports because of its own battle against COVID-19, U.S. stockpiles plummeted. Prices skyrocketed as federal officials, governors and health care systems competed for supplies.

Though federal stockpiles have been replenished, shriveling domestic production has raised concerns that state governments, medical facilities and others could again get stuck scrambling for gear during a future pandemic.

The AP identified more than $125 million in grants to spur production of pandemic supplies made to over 300 business in 10 states — Alabama, Hawaii, Indiana, Kansas, Louisiana, Maryland, Massachusetts, Missouri, New York and Ohio. It’s possible that grants were awarded in additional states, but there is no central clearinghouse to track them.

In November 2020, Alabama awarded one of the single largest grants — nearly $10.6 million from federal pandemic relief funds — to HomTex Inc. The company was to equip a new Selma facility to make 250 million surgical masks and 45 million N95 masks annually. The plant returned $1.8 million of the state grant and has yet to make anything due to a lack of customers.

“I can’t produce product that I can’t sell,” HomTex President Jeremy Wootten said.

Other companies also had trouble living up to political hype.

In October 2020, New York announced eight grants that then-Lt. Gov. Kathy Hochul, now the governor, said were “a model for how we build back better for the post-pandemic future.” Those included $800,000 for newly formed Altor Safety and $1 million for startup firm NYPPE.

But NYPPE’s equipment wasn’t ready until February 2021, by which time the market had changed, President Connor Knapp said.

So Knapp tapped the brakes on his plans. NYPPE still hasn’t sold any N95 masks because it lacks regulatory approval. It just recently scaled up production of surgical masks, after obtaining a U.S. Food and Drug Administration certification that came with its purchase of Altor Safety.

Some PPE manufacturers point to federal regulations as part of the reason for their struggles. Three-ply masks need FDA approval to be marketed for medical use — an important designation for building a long-term customer base.

That process can be time-consuming. Facing delays, Angstrom Manufacturing in Missouri ended up buying another business that already had FDA approval, President Chris Carron said. By then, it was fall 2021 — a year after it received a state grant.

Companies need approval from the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health to market products as N95 respirators, which filter at least 95% of airborne particles.

During the first two years of the pandemic, NIOSH approved 30 new manufacturers — more than seven times the typical number during a similar pre-pandemic period, according to agency data. Some applications remain pending, while numerous others were denied.

Halcyon Shades’ N95 certification was rejected in October because its samples didn’t have head straps attached. While the company works on another application, its equipment sits idle inside the clear plastic-sheet walls of a “clean room” specially built to shield materials from airborne contaminants. Partially finished masks remain paused on a conveyor belt, waiting to be deposited into a cardboard box.

Without federal approval, “we’re just dead in the water,” said Schmersahl, the company owner.

Progress reports filed with the Missouri Department of Economic Development show that nearly all its PPE grant recipients faced challenges by July 2021, especially with sales.

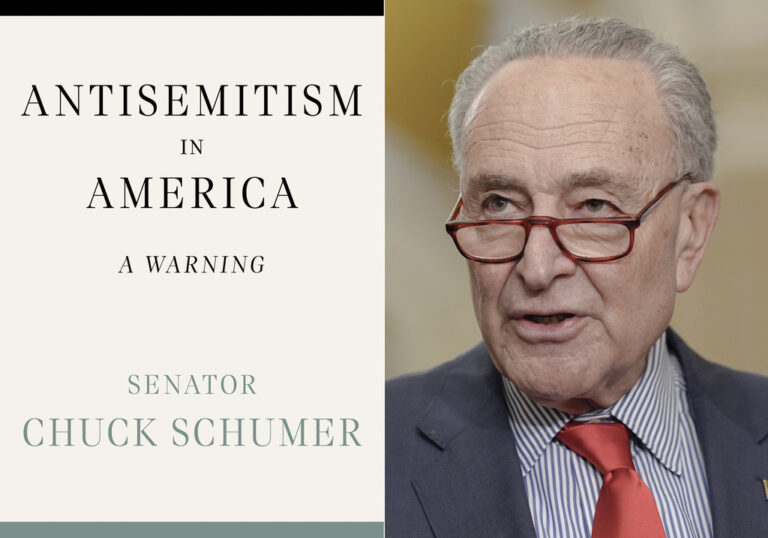

Jim Schmersahl, owner of Halcyon Shades, poses with a machine used to make N-95 masks Friday, March 18, 2022, in University City, Mo. (AP Photo/Jeff Roberson)

Patriot Medical Devices, which received $750,000 from Missouri, hired nearly 100 people as it cranked out millions of masks during a COVID-19 surge in late 2020 and early 2021, CEO Rick Needham said. Fewer than 10 employees remain.

“We felt it was our patriotic duty to do something to help solve the problem,” Needham said. But, he added, “It’s frankly a little bit of a dysfunctional business model at this point.”

Ohio awarded $20.8 million to 73 businesses to manufacture pandemic-related supplies, according to state data. Of 60 businesses that complied with a recent reporting deadline, more than one-third no longer produced PPE by the end of 2021.

Cleveland Veteran Business Solutions, which received a $500,000 grant to get into the PPE business, made about 5 million surgical masks beginning in August 2020. It ultimately halted production in the face of cheaper imports and sold its machines this year, co-founder Taner Eren said.

“It was surprising and disappointing strategically that there wasn’t support for a local PPE manufacturing industry,” Eren said.

The business was among several dozen that banded together to form the American Mask Manufacturer’s Association with the goal of sustaining the industry. The group’s membership has dwindled as more and more go out of business.

Association organizers say the industry has reached a critical point. They want the federal government to treat PPE manufacturers like the nation’s defense industry — entering into long-term contracts to perpetually replenish a stockpile for future pandemics or emergencies.

“If the federal government doesn’t come in and help support the U.S. manufacturing base, it’s almost certainly going to go back to China, and we’ll be just as vulnerable as we were in early 2020 and 2019,” said Brent Dillie, the association chairman and co-founder of Premium-PPE, a Virginia manufacturer started during the pandemic that has shed about two-thirds of its roughly 300 employees.

Infrastructure legislation signed by President Joe Biden took a step toward bolstering domestic suppliers. Effective in February, it required new contracts for PPE purchased by the departments of Health and Human Services, Homeland Security and Veterans Affairs to run for at least two years and be awarded to U.S. producers — unless there’s not sufficient quantity and quality at market prices.

The health and veterans departments said they haven’t bought anything yet. Homeland Security hasn’t answered the AP’s questions. Documents show the government solicited bids due Dec. 6 for up to 381 million U.S.-made surgical masks over three years for its stockpile. No deal has been announced.

Other documents show the government is looking to contract with three major suppliers — 3M, Moldex, and Owens & Minor — for a total of $115 million in U.S-made N95 masks over three years. A justification document says noncompetitive contracts are necessary to preserve capacity for future coronavirus surges or emergencies.

The Biden administration also formed a task force of experts from federal agencies, health care providers, PPE manufacturers and distributors to develop a national strategy for ensuring a “resilient public health supply chain.” Its work is expected to extend for years.

Some manufacturers said they can’t wait long for a federal life preserver.

Dentec Safety Specialists is wrapping up a contract to supply 125,000 rubber reusable respirators and 500,000 filtration cartridges from its Kansas facility for the national stockpile, said President Claudio Dente. It needs more orders soon to prevent layoffs, he said.

“I thought that COVID would really change the mindset of the people, the governments and manufacturing,” Dente said. But he added: “The general marketplace is reverting back to their old ways — meaning looking to buy product from China.”

(AP)