Jury selection began Thursday in the federal trial for three former Minneapolis police officers who are charged with violating George Floyd’s constitutional rights while fellow Officer Derek Chauvin used his knee to pin the Black man to the street.

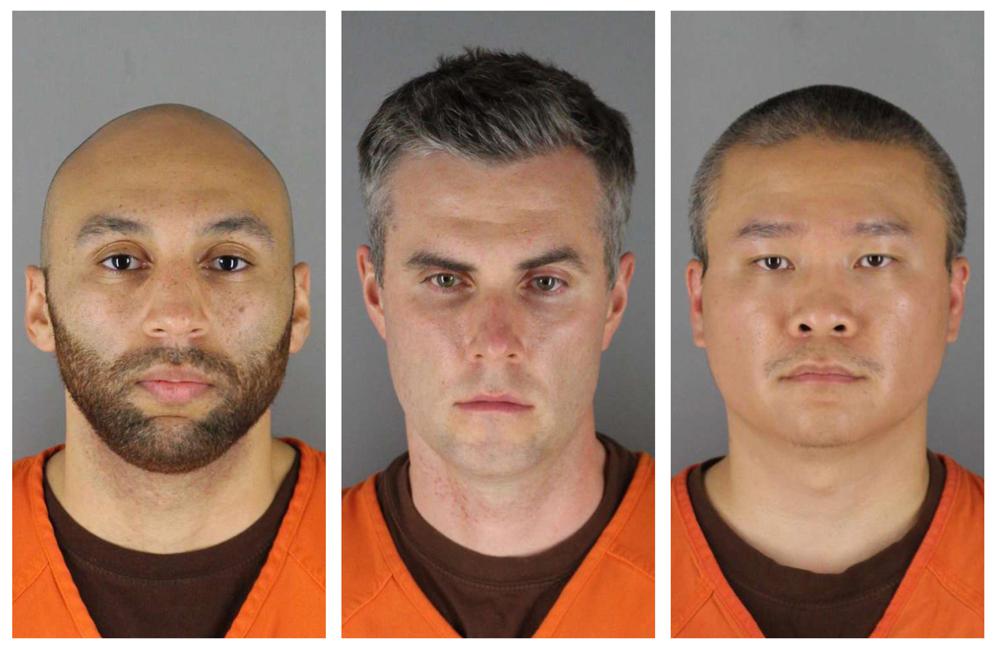

J. Kueng, Thomas Lane and Tou Thao are broadly charged with depriving Floyd of his civil rights while acting under government authority. Separately, they’re charged in state court with aiding and abetting both murder and manslaughter.

Legal experts say the federal trial will be more complicated than the state trial, scheduled for June 13, because prosecutors in this case have the difficult task of proving the officers willfully violated Floyd’s constitutional rights — unreasonably seizing him and depriving him of liberty without due process.

“In the state case, they’re charged with what they did. That they aided and abetted Chauvin in some way. In the federal case, they’re charged with what they didn’t do — and that’s an important distinction. It’s a different kind of accountability,” said Mark Osler, a former federal prosecutor and professor at the University of St. Thomas School of Law.

Phil Turner, another former federal prosecutor, said prosecutors must show the officers should have done something to stop Chauvin, rather than show they did something directly to Floyd.

Would-be jurors have already answered an extensive questionnaire, and were being brought into a federal courtroom in St. Paul in groups, where U.S. District Judge Paul Magnuson was questioning them. The process will continue until a group of 40 is chosen. Then, each side will get to use their challenges to strike jurors. In the end, 18 jurors will be picked, including 12 who will deliberate and six alternates.

The judge told potential jurors they should let him know if any responses to their questionnaires have changed. He also asked each to stand and talk about themselves, including where they live, their job history, education, military service, hobbies and families.

He also acknowledged the media attention on the case, saying, “I’m sure all of you know something about what happened to George Floyd.”

Magnuson has said he believes jury selection could be done in two days, unlike the state trial for Chauvin, where the judge and attorneys questioned each juror individually and spent more than two weeks picking a panel.

He said the trial is expected to last four weeks.

Floyd, 46, died on May 25, 2020, after Chauvin pinned him to the ground with his knee on Floyd’s neck for 9 1/2 minutes while Floyd was facedown, handcuffed and gasping for air. Kueng knelt on Floyd’s back and Lane held down his legs. Thao kept bystanders from intervening.

Chauvin was convicted in April on state charges of murder and manslaughter and is serving a 22½-year sentence. In December, he pleaded guilty to a federal count of violating Floyd’s rights.

Federal prosecutions of officers involved in on-duty killings are rare. Prosecutors face a high legal standard to show that an officer willfully deprived someone of their constitutional rights; an accident, bad judgment or negligence isn’t enough to support federal charges.

Essentially, prosecutors must prove that the officers knew what they were doing was wrong, but did it anyway.

Kueng, Lane and Thao are all charged with willfully depriving Floyd of the right to be free from an officer’s deliberate indifference to his medical needs. The indictment says the three men saw Floyd clearly needed medical care and failed to aid him.

Thao and Kueng are also charged with a second count alleging they willfully violated Floyd’s right to be free from unreasonable seizure by not stopping Chauvin as he knelt on Floyd’s neck. It’s not clear why Lane is not mentioned in that count, but evidence shows he asked twice whether Floyd should be rolled on his side.

Both counts allege the officers’ actions resulted in Floyd’s death.

Federal civil rights violations that result in death are punishable by up to life in prison or even death, but those stiff sentences are extremely rare and federal sentencing guidelines rely on complicated formulas that indicate the officers would get much less if convicted.

“This trial is going to present an evolutionary step beyond what we saw at the Chauvin trial because we’re not looking at the killer, but the people who enable the killer. And that gets a step closer to the culture of the department,” Osler said.

(AP)