The air conditioners hum constantly in the lab at the Wellcome Sanger Institute, countering the heat thrown off by rows of high-tech sequencing machines that work seven days a week analysing the genetic material of COVID-19 cases from throughout the U.K.

The laboratory is one example of how British scientists have industrialised the process of genomic sequencing during the pandemic, cutting the time and cost needed to generate a unique genetic fingerprint for each coronavirus case analysed. That made the UK a world leader in COVID-19 sequencing, helping public health authorities track the spread of new variants, develop vaccines and decide when to impose lockdowns.

But now researchers at the Sanger Institute in Cambridge and labs around the UK have a new mission: sharing what they’ve learned with other scientists because COVID-19 has no regard for national borders.

The omicron variant now fuelling a new wave of infection around the world shows the need for global cooperation, said Ewan Harrison, a senior research fellow at Sanger. Omicron was first identified by scientists in southern Africa who quickly published their findings, giving public health authorities around the world time to prepare.

Since dangerous mutations of the virus can occur anywhere, scientists must monitor its development everywhere to protect everyone, Harrison said, drawing a parallel to the need to speed up vaccinations in the developing world.

“We need to be prepared globally,” he said. “We can’t just kind of put a fence around an individual country or parts of the world, because that’s just not going to cut it.’’

Britain made sequencing a priority early in the pandemic after Cambridge University Professor Sharon Peacock identified the key role it could play in combating the virus and won government funding for a national network of scientists, laboratories and testing centres known as the COVID-19 Genomics UK Consortium. This allowed the UK to mobilise academic and scientific expertise built up since British researchers first identified the chemical structure of DNA in 1953.

The consortium is now backing efforts to bolster global sequencing efforts with a training program focused on researchers in developing countries. With funding from the UK government, the consortium and Wellcome Connecting Science plan to offer online courses in sampling, data sharing and working with public health agencies to help researchers build national sampling programs.

“There is inequity in access to sequencing worldwide, and (the project) is committed to contributing toward efforts that close this gap,” the group said, announcing plans to offer the first courses early this year.

By sequencing as many positive cases as possible, researchers hope to identify variants of concern as quickly as possible, then track their spread to provide early warnings for health officials.

The UK has supplied more COVID-19 sequences to the global clearinghouse than any country other than the US and has sequenced a bigger percentage of its cases than any large nation worldwide.

Researchers in the UK have submitted 1.68 million sequences, covering 11.7 per cent of reported cases, according to data compiled by GISAID, which promotes rapid sharing of information about COVID-19 and the flu. The US has supplied 2.22 million sequences, or 3.8 per cent of its reported cases.

Most countries are doing some sequencing but the volume and speed varies greatly. While 205 jurisdictions have shared sequences with GSAID, more than half have sequenced and shared less than one per cent of their total cases.

Over the past two years, labs around the U.K. have refined the process of gathering and analysing COVID-19 samples until it resembles just-in-time manufacturing strategies. Specific protocols cover each step — from swab to sequence to reporting — including systems to ensure that supplies are in the right place at the right time to keep the work flowing.

That has helped slash the cost of analysing each genome by 50 per cent while reducing the turnaround time from sample to sequence to five days from three weeks, according to Wellcome Sanger.

Increasing sequencing capacity is like building a pipeline, according to Dr Eric Topol, chair of innovative medicine at Scripps Research in San Diego, California. In addition to buying expensive sequencing machines, countries need supplies of chemical reagents, trained staff to carry out the work and interpret the sequences, and systems to ensure that data is shared quickly and transparently.

Putting all those pieces in place has been a challenge for the US, let alone developing countries, Topol said.

Genomic sequencing “as a surveillance tool worldwide is essential, because many of these low- and middle-income countries don’t have the sequencing capabilities, particularly with any reasonable turnaround time,” he said. “So, the idea that there’s a helping hand there from the Wellcome Center is terrific. We need that.”

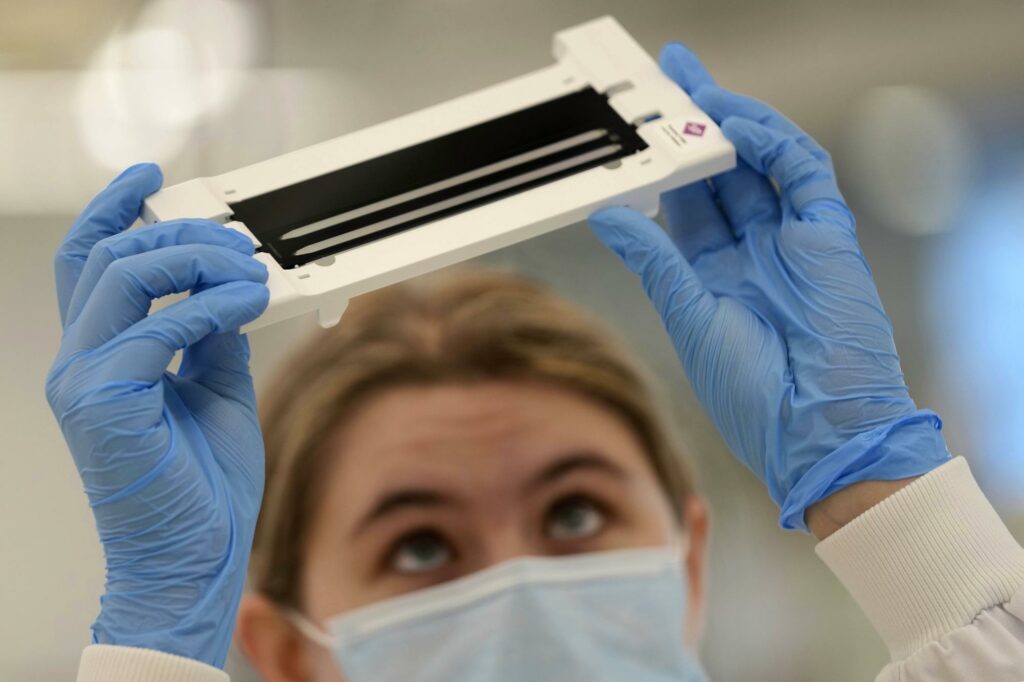

At Wellcome Sanger’s state-of-the-art lab, samples arrive constantly from around the country. Lab assistants carefully prepare the genetic material and load it onto plates that are inserted into the sequencing units that decipher each sample’s unique DNA code. Scientists then analyse the data and compare it with previously identified genomes to track mutations and see if new trends are emerging.

With COVID-19 constantly mutating, the priority is to check for new more dangerous variants, including those that may be resistant to vaccines, Harrison said. The information is critical in helping researchers modify existing vaccines or develop new ones to combat the ever-changing virus.

Harrison praised South Africa for its work on the highly transmissible omicron variant and quickly sharing its research with international authorities. Unfortunately, many countries then restricted travel to South Africa, harming its economy.

Harrison said developing nations must be encouraged to publish data on new variants without fear of economic repercussions because punishing countries like South Africa will only hamper information sharing that is needed to combat COVID-19 and future pandemics.

“The key thing, obviously, is this constant routine surveillance,” he said. “And I think the most important step now is increasing that globally.’’

For now, it also means lots of work, every day, to keep watch. But such vigilance has its benefits, said Tristram Bellerby, the lab’s manager.

“It’s been good to see that our work has been valuable in finding these new variants,” he said. “I hope at some point it could aid us in getting out of this situation we find ourselves in.″

(AP)