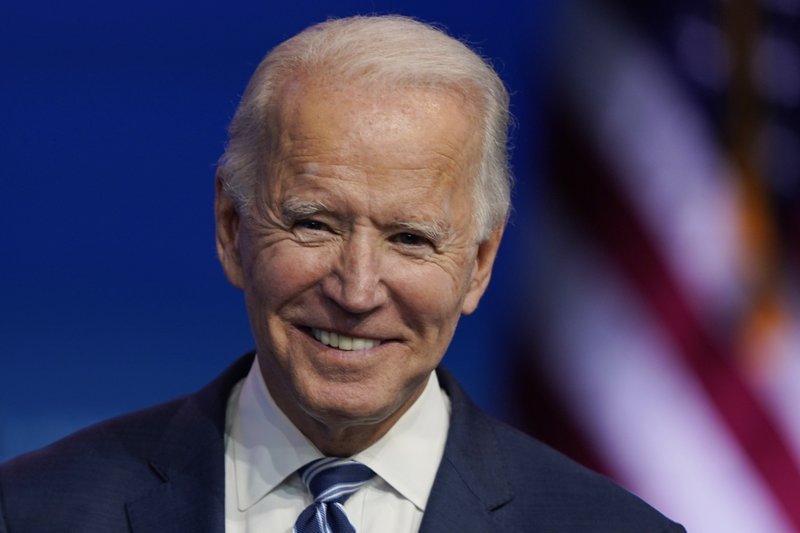

President-elect Joe Biden feels at home on Capitol Hill, but the place sure has changed since he left.

The clubby atmosphere that Biden knew so well during his 36-year Senate career is gone, probably forever. Deal-makers are hard to find. And the election results haven’t dealt him a strong hand to pursue his legislative agenda, with Democrats’ poor performance in down-ballot races likely leaving them without control of Congress.

The dynamic leaves Biden with little choice but to try to govern from the vanishing middle of a Washington that’s been badly ruptured by the tumult of the last decade. With the forces of partisanship and gridlock entrenched, ending what Biden called the “grim era of demonization” could be the central challenge of his presidency — and one that could prove vexing if forces on the left and right refuse to go along.

“There is a certain opportunity for bipartisanship, but it is all going to be deals in the middle,” said Rohit Kumar, a former aide to Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell, R-Ky. “What I don’t know is whether the (Democratic and Republican) parties will allow them to do that because the parties have gotten a lot more polarized.”

While it is not settled, Biden faces a high likelihood of becoming the first Democrat in modern history to assume office without his party controlling Congress. Republicans are favored to retain control of the Senate heading into two runoff elections in Georgia in January. Democrats have already won the House.

GOP control of the Senate would force Biden to curtail his ambitions, all but guaranteeing that big issues like climate change, immigration and expanding “Obamacare” remain mostly unaddressed.

But it would also create space for a different kind of legislative agenda — one founded on bipartisanship and consensus that would seem to play to Biden’s strengths. And some lawmakers say voters made clear in the election that governance from the middle is exactly what they want.

Among them is Sen. Susan Collins, R-Maine, who emerged from a brutal reelection campaign empowered to pursue a brand of pragmatic centrism that was once common among lawmakers but is now quite rare.

“I have seen, based on the number of phone calls that I have received from both the Democratic senators and Republican colleagues, a real interest in trying to expand the center and work together to confront some of the challenges facing our nation,” Collins said. “And I’m encouraged by that.”

The glass half-full also depends on a sympathetic appraisal of McConnell, a much-loathed nemesis of Capitol Hill Democrats with a penchant for hardball tactics — and who is no stranger to obstructionism.

McConnell is an old friend of Biden’s, and as vice president, Biden worked successfully with the Kentucky Republican to avert several tax- and budget-related crises during the Obama administration, including a tax increase on higher-income earners in exchange for renewing most of the 2001 Bush tax cuts.

“Those deals were largely struck out of necessity in moments of crisis — fiscal cliff, debt limit, government shutdowns — those types of things,” said Brendan Buck, a former top aide to former House Speaker Paul Ryan, R-Wis. “That’s when they had to get together and get things done. I don’t know that there’s a great deal of history of proactively coming together on big policy issues.”

McConnell hasn’t let much legislation hit the Senate floor recently, but has the muscle memory to do bipartisan deals when he sees them. Often, these smaller-bore bills offer political benefits to his members, like a 2016 bill to fight the opioid menace or a widely backed public lands bill this year. Other recent deals include COVID relief, a 2015 highway bill and a 2016 cancer-fighting “moonshot” bill that was delivered as a goodwill gesture to Biden, who lost his son Beau to brain cancer in 2015.

But the space for bipartisanship has contracted, with hardly any political middle remaining on Capitol Hill. Soon there will no longer be any white southern Democrats in the House or Senate, while in the GOP there are only a handful of moderates left.

Biden, by contrast, served in a Senate where Democrats represented strongly Republican states in the South and the Great Plains, and where Republicans represented now-Democratic bastions like Minnesota and Oregon. Compromise came more easily under such circumstances. Now the party breakdown of the chamber is mostly determined by whether a state is red or blue on the presidential map, with Republicans dominating the South and Midwest and Democrats controlling the West Coast and most of New England and the Middle Atlantic.

Democrats aren’t giving up on the two Georgia runoff elections, given the stakes. Control of the chamber would afford Biden the opportunity to craft a Democrats-only budget bill that could reverse some of President Donald Trump’s tax cuts, expand the Affordable Care Act, and boost tax credits for the poor.

“The difference between a 50-50 Senate controlled by Democrats and a 51-49 Republican-controlled Senate could not be any more stark,” said veteran Democratic Sen. Dick Durbin of Illinois.

But even if Democrats win both Georgia runoffs, the hopes of progressives for ramming through a liberal agenda by getting rid of the legislative filibuster — the 60-vote threshold for most legislation — are simply gone.

That’s a disappointing blow to the left but could be welcomed by Democratic moderates who warn the party’s messaging did not resonate in swing districts, and who would prefer to focus their energies on bipartisan areas such as infrastructure and rural broadband, COVID relief and annual spending bills.

“There is the capacity within the Democratic Caucus to move forward and make some important gains on these issues and understanding that people are not always going to get 100% of what they want,” said Sen. Chris Van Hollen, D-Md.

The Biden-McConnell relationship is obviously crucial. The Kentucky Republican’s stewardship of the Senate has been marked by sharp elbows and sometimes cutthroat tactics. The Senate floor has been a legislative dead zone of late, but it could be a mistake to assume McConnell will be satisfied by simply stifling Biden’s agenda.

Instead, McConnell could seek opportunities to put points on the board for a challenging midterm cycle with competitive races and another shot at the White House in 2024.

“He has a remarkable record of shape-shifting to run his conference in a unique manner determined by the political imperative of the moment,” said former Senate Democratic leadership aide Mike Spahn. “So I would expect that to happen again.”

(AP)