With winter looming and confirmed viral cases rising, Bob Szuter’s craft brewery and restaurant in Columbus, Ohio, could use another government lifeline to help survive until spring.

So could many restaurants and bars that buy his beer. Szuter knows of nearly 20 in the region that have folded, with many others “limping along.”

As a small businessman, Szuter benefited from the multi-trillion-dollar stimulus aid that Congress passed in March after the pandemic recession flattened the economy. Countless other business people did, too, along with millions of laid-off workers, struggling states and localities and individual Americans.

All that aid is gone. Yet prospects for more federal stimulus this year appear all but dead, clouding the future for the unemployed, for small businesses like Szuter’s and for the economy as a whole.

Now, with confirmed COVID cases surging across the United States, so is the risk that the economy could weaken again as more people choose to hunker down at home — and that even more stimulus might be needed next year than negotiators in Washington are contemplating. Johns Hopkins University data shows that more than 83,000 infections were reported both Friday and Saturday — well above the previous record high. The University of Washington’s Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation forecasts that the U.S. death toll, now roughly 225,000, could top 318,000 by Jan. 1.

Since early September, Szuter’s restaurant has enjoyed a modest revival with outdoor dining on a street converted to a patio. Szuter, the co-owner with his father of Wolf’s Ridge Brewing, is investing in tents and heaters. But he worries that cold weather and the resurgence of the virus will depress business again as more people stay away.

“It’s been a struggle,” said Szuter, 35. “Any sort of additional support would be extremely helpful at this point, especially going into the cooler months.”

It’s possible, if unlikely, that a small economic-relief package will be approved in a post-election “lame duck” session of Congress. More likely, a broad rescue measure could be enacted early next year, particularly if Joe Biden wins the presidency and his fellow Democrats capture the Senate. Even if President Donald Trump were to win re-election, most analysts foresee at least a modest stimulus next year.

Until then, economists worry that the United States risks repeating a mistake made after the 2008-2009 Great Recession, when limits on federal spending and layoffs by states and localities hindered a recovery. More aid to states and cities could forestall further layoffs. States, which are generally required to balance their budgets, must now do so with less revenue.

With no stimulus likely the rest of this year, economists at Goldman Sachs have slashed their growth forecast for the October-December quarter to a 3% annual rate from 6%.

Eric Winograd, chief U.S. economist at AllianceBernstein, likened federal aid to a bridge being built from just before the pandemic struck to the point where it has been controlled and business can return to normal — most likely after a vaccine is developed and widely distributed.

“How long does the bridge have to be, and will policymakers have the will and ability to build it?” he asked. “It’s premature to withdraw stimulus now.”

Winograd predicts that more federal aid will be approved early next year and that the economy will grow 3.4% for 2021, a solid pace. Yet even at that rate, the economy wouldn’t regain its pre-pandemic level until perhaps early 2022. Without more stimulus, Winograd forecasts that growth for 2020 could erode to a sluggish 1.5%.

For now, Szuter sells craft beer online and has reopened indoor dining. But indoor dining is generating less than half the business he enjoyed before the pandemic. Fear of the virus, Szuter thinks, has kept many customers away. His staff, which has shrunk from 77 to 55, worries about getting sick, too. The persistence of the virus and the government’s failure so far to control it have convinced Szuter that more government aid is needed.

Federal Reserve officials have expressed similar concerns. Lael Brainard, a Fed board member, warned last week that the economy’s most severe risks are the lack of further stimulus and the persistent viral outbreak. A premature end to federal aid would depress hiring and spending and cause more business failures, Brainard told the Society of Professional Economists.

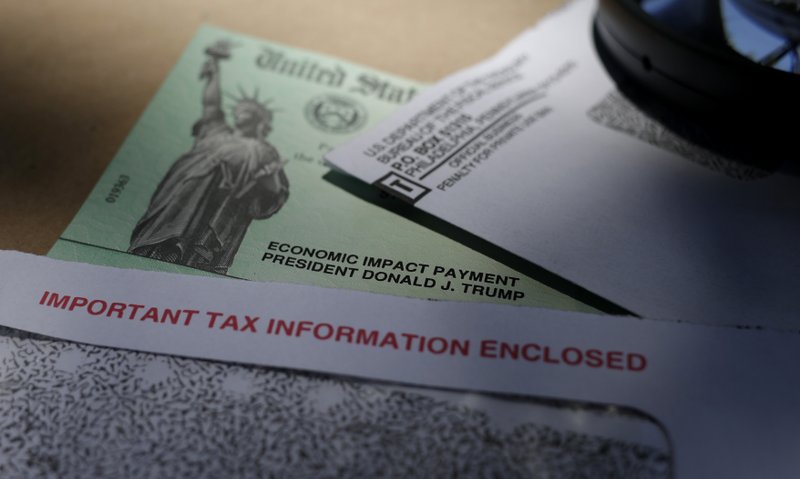

The $2 trillion CARES Act that Congress enacted in March managed to ease the pain of the recession by boosting incomes and spending,, and supporting small businesses. Fed Chair Jerome Powell said the stimulus prevented a recessionary “downward spiral,” in which unemployed Americans would slash spending, triggering further job cuts and spending reductions. Without additional aid, Powell warned, those dynamics could re-emerge.

Back in April, Americans’ overall income actually soared even though tens of millions of people had lost jobs. That was thanks to a $600-a-week federal unemployment benefit and $1,200 stimulus checks that went to most individuals under the CARES Act. Those payments enabled many of the jobless to rebuild savings, allowing them to keep spending even after the $600 supplement expired in July.

A study by the JPMorgan Chase Institute found that the unemployed roughly doubled their savings from March to July and boosted their spending by 22% during that period. But by August, once the $600-a-week benefit had lapsed, they cut spending back 14%.

Thanks in part to the stimulus money, the pace of retail sales has fully regained its pre-pandemic level. Yet the savings for many will eventually run out, forcing the jobless to cut spending and slow growth.

Michael Brey, the president of Hobby Works, with two stores in Maryland that sell jigsaw puzzles, model trains and other hobby equipment, has enjoyed exponential growth in his online sales since the pandemic struck, thanks in part to the CARES Act.

When his customers ordered online, some of them even mentioned that they were spending part of their stimulus checks with him. But Brey worries that holiday sales this year will slow without further federal support.

“You do wonder what’s going to happen going forward,” he said. “What are all the people whose jobs haven’t come back going to do?”

(AP)