Blood tests for the coronavirus could play a key role in deciding whether millions of Americans can safely return to work and school. But public health officials warn that the current “Wild West” of unregulated tests is creating confusion that could ultimately slow the path to recovery.

More than 70 companies have signed up to sell so-called antibody tests in recent weeks, according to U.S. regulators. Governments around the world hope that the rapid tests, which typically use a finger-prick of blood on a test strip, could soon ease public restrictions by identifying people who have previously had the virus and have developed some immunity to it.

But key questions remain: How accurate are the tests, how much protection is needed and how long will that protection last.

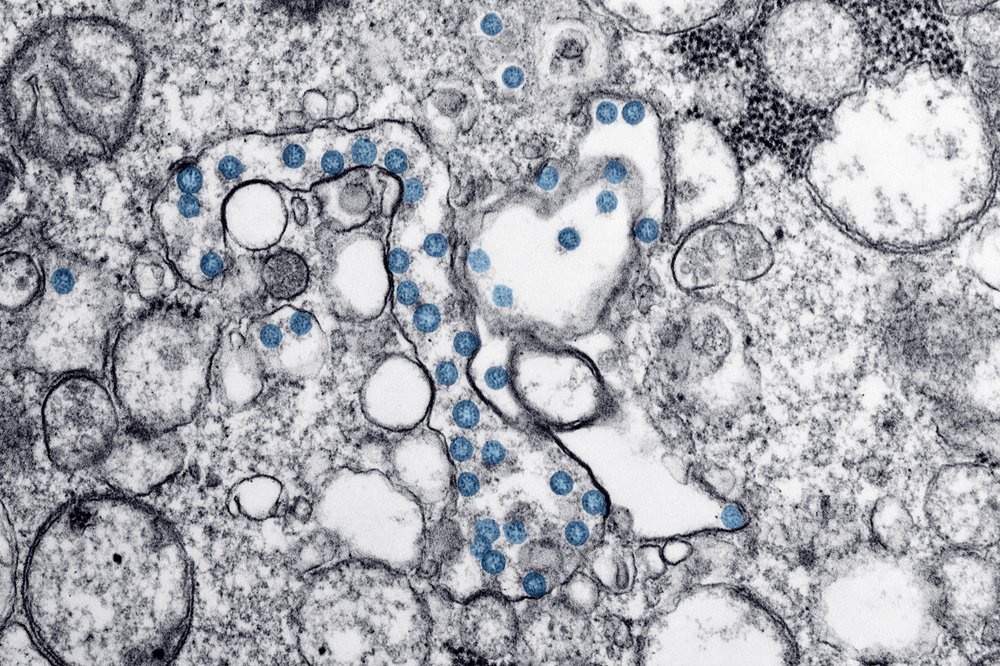

The blood tests are different from the nasal swab-based tests currently used to diagnose active COVID-19 infections. Instead, the tests look for blood proteins called antibodies, which the body produces days or weeks after fighting an infection. The same approach is used for HIV, hepatitis, Lyme disease, lupus and many other diseases.

Because of the relative simplicity of the technology, the Food and Drug Administration decided to waive initial review of the tests as part of its emergency response to the coronavirus outbreak.

Right now, the tests are most useful for researchers studying how the virus has spread through the U.S. population. The government said Friday it has started testing 10,000 volunteers. The White House has not outlined a broader plan for testing and how the results might be used.

With almost no FDA oversight of the tests, “It really has created a mess that’s going to take a while to clean up,” said Eric Blank of the Association for Public Health Laboratories. “In the meantime, you’ve got a lot of companies marketing a lot of stuff and nobody has any idea of how good it is.”

Members of Blank’s group, which represents state and local lab officials, have urged the FDA to revisit its lax approach toward the tests. That approach essentially allows companies to launch as long as they notify the agency and include disclaimers. Companies are supposed to state that their tests have not been FDA-approved and cannot rule out whether someone is currently infected.

Last week, FDA Commissioner Stephen Hahn said in a statement that the agency will “take appropriate action” against companies making false claims or selling inaccurate tests.

During an interview Sunday on NBC’s “Meet the Press,” Hahn expressed “concern” that tests being sold “may not be as accurate as we’d like them to be.”

“What we don’t want are wildly inaccurate tests,” he said. “That’s going to be much worse, having wildly inaccurate tests than having no test.”

Dr. Allison Rakeman of New York City’s Public Health Laboratory says some local hospitals are assuming the tests, which are listed on FDA’s website, “have been vetted, when they have not.”

The danger of faulty testing, Rakeman says, is that people will mistakenly conclude that they are immune or are no longer spreading the virus.

“Then somebody goes home and kisses their 90-year-old grandmother,” said Rakeman. “You don’t want to give someone a false sense of security.”

For most people, the new coronavirus causes mild or moderate symptoms, such as fever and cough that clear up in two to three weeks. For some, especially older adults and people with existing health problems, it can cause more severe illness, including pneumonia, and death.

For many infections, antibody levels above a certain threshold indicate that the person’s immune system has successfully fought off the virus and is likely protected from reinfection. For COVID-19, it’s not yet clear what level of antibodies render patients immune or how long immunity might last.

Adding to the confusion is the fact that both legitimate companies and fraudulent operators appear to be selling the kits. Distinguishing between the two can be a challenge.

Officials in Laredo, Texas, reported this month that some 2,500 antibody tests set for use at a local drive-thru testing site were likely frauds. City officials had ordered what they were told were “FDA-approved COVID-19 rapid tests,” from a local clinic. But when they checked the test’s accuracy, it fell well below the range promised, the city said in a statement.

Examples of U.S. companies skirting the rules appear online and in emails sent to hospitals.

Promotional emails sent to hospitals and reviewed by The Associated Press failed to include required disclaimers. Some kits sold on websites promote themselves as “FDA-approved” for home testing. The agency has not yet approved any COVID-19 home test. The blood tests have to processed by a lab.

“If you see them on the internet, do not buy them until we can give you a test that’s reliable for all Americans,” said Dr. Deborah Birx, coordinator of the White House coronavirus task force, at a recent briefing.

20/20 BioResponse is one of dozens of U.S. companies selling the tests to hospitals, clinics and doctor’s offices. The Rockville, Maryland-based company imports the tests from a Chinese manufacturer but CEO Jonathan Cohen says his company independently confirmed its performance in 60 U.S. patients. He estimates the company has shipped 10,000 tests and has had to limit orders due to demand.

He said antibody tests are not a “panacea but they’re not garbage either.”

Cohen called them “a tool in the toolbox that will have some value along with other tests.”

The company’s test is registered on the FDA website and includes all the required disclaimers.

To date, the FDA has only authorized one COVID-19 antibody test from North Carolina diagnostics company Cellex. The agency used its emergency powers, meaning a formal review is still needed.

The White House has also tried to temper expectations for the tests, while still promising that millions will soon be available.

Dr. Brett Giroir, the federal health official overseeing U.S. testing, told reporters a week ago that the FDA and other agencies are working to confirm the accuracy of the antibody tests.

“We’re going to be very careful to make sure that when we tell you you’re likely immune from the disease … the test really said that,” Giroir said.

(AP)