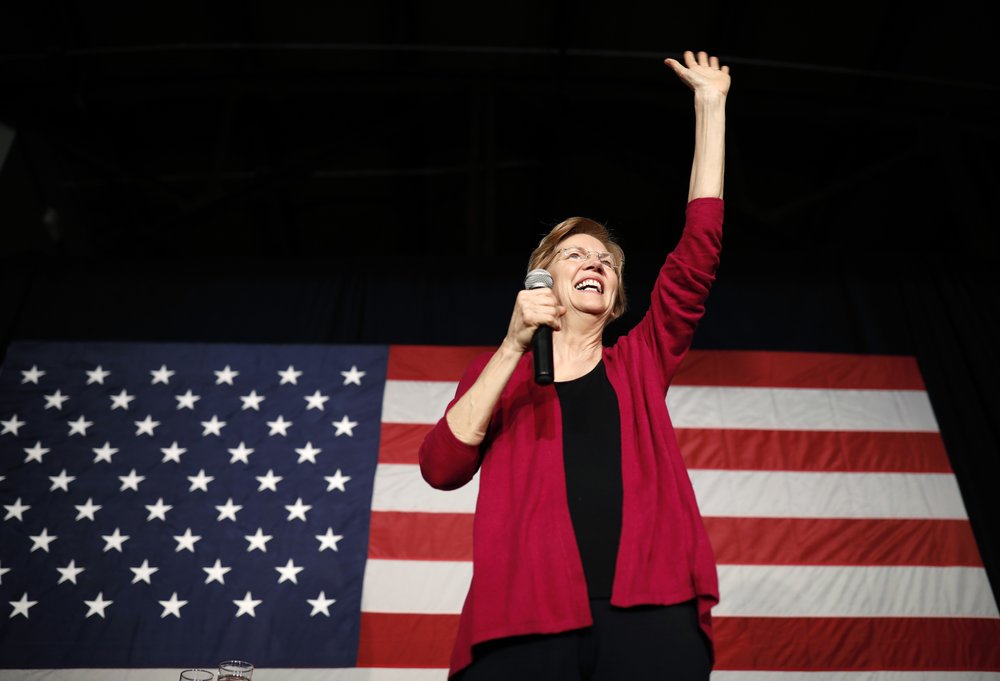

When Sen. Elizabeth Warren took the stage earlier this month at this city’s ornate Orpheum Theatre, Tricia Currans-Sheehan posed a pointed question to the expected presidential contender.

“Why did you undergo the DNA testing and give Donald Trump more fodder to be a bully?” the Iowa college professor asked, referring to a genetic analysis the Massachusetts Democrat released last fall to rebut President Donald Trump’s repeated jabs about her Native American ancestry.

Warren had a simple response: “I can’t stop Donald Trump from doing what he’s going to do.” After another woman in the crowd retorted, “Yes, you can,” Warren gently reiterated that “I can’t stop him from hurling racial insults. I don’t have the power to do that.”

The scene demonstrates the challenge Warren, who has launched a presidential exploratory committee, and dozens of other White House hopefuls will face as the Democratic primary gets underway. They must decide how — and whether — to respond to Trump’s pugnacious and insensitive attacks on his political opponents. If they punch back too hard, they could be accused of playing Trump’s game. If they ignore him entirely, they risk appearing unprepared to take on a president who knows few boundaries.

Warren was tested again late Sunday when Trump seized on one of her social media videos to issue a tweet that made light of two massacres of Native Americans. South Dakota’s two Republican senators distanced themselves from Trump’s comment, which drew condemnation from Native American officials. But Warren herself didn’t immediately engage.

In an interview this week, Warren called the tweet “disgusting” for mocking “one of the darkest moments in American history,” the deadly assault on hundreds of Native American women and children at Wounded Knee, South Dakota. Yet she also hinted at a bigger reason for not responding right away.

“He needs to focus on getting the government open, on doing his job,” she said. “He hopes that he can draw attention elsewhere, but it’s not working.”

Others considering 2020 campaigns also indicate that, whenever possible, they plan to ignore Trump’s personal needling and focus on issues.

“I don’t want to waste my time on negativity” when voters “want to hear positive,” Sen. Cory Booker of New Jersey said in an interview in which he also commended Warren, his likely rival for the Democratic nomination.

“What’s more important is what Sen. Warren is talking about, and she’s putting great ideas out there,” Booker said. “Why let anybody distract from the compelling things she’s saying and how she’s presenting herself?”

But Sen. Amy Klobuchar of Minnesota, another potential 2020 candidate, suggested Democrats face a tricky challenge.

“You have to stand your ground” in response to Trump, she said in an interview, but also take care about “how you do it, because he wants you to go down in the rabbit hole. He wants to define the agenda every single day.”

While “everyone makes their own decision” on replying to a Trump taunt, she added, “I think it is very important to put it in its place and, while you respond, you do not spend weeks talking about him. Because that is exactly what he wants.”

Other possible Democratic candidates haven’t hesitated to tangle with Trump. Sen. Sherrod Brown recalled that when Trump slammed him over the closure of a General Motors plant in his home state, he poked the president for seeking “an Ohio Democrat to blame” while the GOP held power in the state.

Asked how he would respond if Trump got more personal, Brown didn’t shrink. The president “talks like an idiot,” Brown said. “And I don’t think that serves anybody well to answer every time he says something stupid, or something that’s a lie.” Democrats, he added, should “talk about the issues that matter to the public.”

Former Vice President Joe Biden, who is mulling another presidential campaign, said last March that he would have “beat the hell out of” Trump if they were in high school together, citing Trump’s now-infamous 2005 comments about assaulting women with impunity.

Inside the White House, Trump’s Sunday tweets mocking Warren were widely joked about by staff weary from the government shutdown, according to two aides, and the president repeatedly mocked Warren’s video in private conversations with aides and outside advisers. White House officials and Trump allies said the president is already an active participant in the Democratic race.

The aides spoke on the condition of anonymity to discuss internal White House dynamics.

Attention from Trump can drive up fundraising and elevate a candidate above a crowded field. But responding to attacks also distracts from a candidate’s message, as Trump’s rivals in the 2016 GOP primary learned as he bedeviled them with name-calling. Trump goaded Sen. Marco Rubio of Florida into making a thinly veiled insult of his manhood that quickly backfired, and weeks later sucked Texas Sen. Ted Cruz into a brutal back-and-forth about an insult he leveled at Cruz’s wife.

Beyond Warren, Trump has hurled insults at other Democrats, labeling Sen. Bernie Sanders as “crazy.” Trump once asked a crowd to choose between two demeaning names for Biden and deployed innuendo when saying Sen. Kirsten Gillibrand of New York “would do anything for campaign contributions.”

In 2016, Democratic nominee Hillary Clinton was the subject of a near-daily barrage of personal attacks from Trump. Her team decided she would ignore personal insults and criticisms of her husband and of the Clinton Foundation, according to her 2016 communications director Jennifer Palmieri.

However, Clinton publicly defended parents of a Muslim U.S. Army captain killed in Iraq and former Miss Universe Alicia Machado after Trump criticized them. Those instances were aimed at standing up for others, Palmieri said, while a candidate who responds to a personal taunt risks appearing small and distracted from the more important issues facing the nation.

“It comes across as very self-absorbed. Then the campaign ends up in this tit-for-tat with Donald Trump, and not about the voters,” Palmieri said.

Responding to an attack on someone else in “defense of inclusivity or some larger truth” is a good idea, Palmieri said, but “don’t do it in defense of yourself. Then you’re sinking to Trump’s level.”

Warren’s release of the DNA test remains a concern for some voters as she hits the trail. Tricia Currans-Sheehan, the Iowa teacher who asked Warren about it in Sioux City, drew a contrast between what she described as Warren playing “into Trump’s hand” and the “poise” that House Speaker Nancy Pelosi displayed in another showdown with the president in December.

Retired Sioux City teacher Colleen Sernett-Shadle said after Warren’s event ended that “I worry” the Democratic candidate might “give in” to Trump on other attacks.

Other Iowa activists shared the call for discretion.

“We’re wrong if we’re going to go out and be as visceral as Trump is,” said Nancy Bobo, a Des Moines Democrat and early 2008 backer of former President Barack Obama. “It’s going to come down to soft skills to pull off a win. By that, I mean style, someone who can show real strength to be a counter to all the divisiveness.”

(AP)