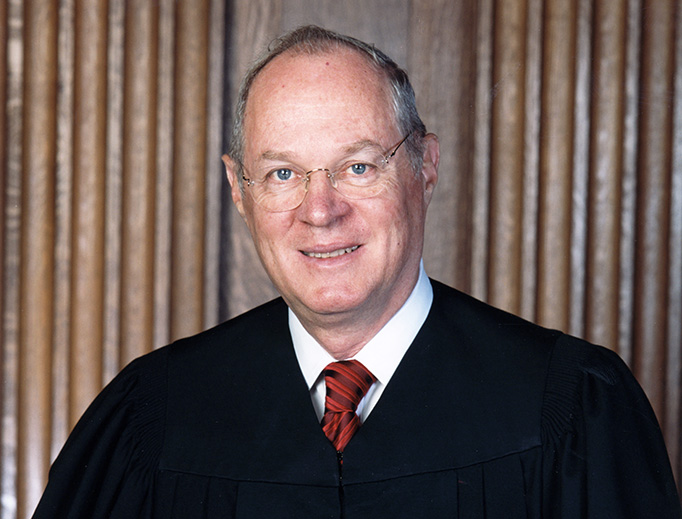

Justice Anthony Kennedy has his law clerks lined up for next year. He plans to teach in Salzburg, Austria, in July, as he has done almost every summer for more than two decades. In short, there are no outward signs that the 81-year-old justice is in his final months on the Supreme Court.

So why are liberals in a state of heightened anxiety that Kennedy might leave? And why are some conservatives hopeful that, appearances aside, Kennedy could step down after more than 30 years on the high court?

Because if he goes, President Donald Trump gets to nominate his successor, whom a slim Republican Senate majority is likely to confirm. The replacement justice would be more conservative than Kennedy and the right would have a solid working majority of the nine justices.

The speculation reflects the darkest fears and fondest wishes of people who care about the court on both sides of the political spectrum. As the justice closest to the middle on an otherwise starkly divided court, Kennedy controls the outcome of a disproportionate share of big-ticket cases.

That divide allows Kennedy to decide how far to the right or left the court moves on a range of issues, including abortion, gun rights, capital punishment, affirmative action, and voting rights.

Filling the vacancy could be as contentious as it was when Justice Lewis Powell, Kennedy’s predecessor, retired in 1987 and President Ronald Reagan settled on Kennedy only after his first two choices for the seat failed, said David Yalof, chairman of political science at the University of Connecticut.

“The difference is that in 1987 you had a Democratic Senate face off against a Republican president in his final two years in office. Here, you have a Republican Senate and a Republican president in his first two years in office,” Yalof said.

The concern among liberals is palpable. Kennedy is nearly 82 and the average retirement age of the last 15 justices who retired is just over 77 years. That includes John Paul Stevens, who was 90 when he retired in 2010 and 58-year-old Abe Fortas, who left the court amid revelations of financial improprieties in 1969.

If Kennedy were to announce his retirement this spring, it would inject the court into the middle of the midterm congressional elections and put his “critical fifth vote in the hands of perhaps the least competent president in modern history to manage and value it,” said Elizabeth Wydra, president of the liberal Constitutional Accountability Center.

The New York Times editorial board penned an open letter to Kennedy on Sunday, imploring him to hang on. “How can we put this the right way? Please don’t go,” it said.

The two older justices, Ruth Bader Ginsburg, 85, and Stephen Breyer, 79, are Democratic appointees who are unlikely to go anywhere during a Trump administration if they can help it.

The pleas for Kennedy to stay come in a term when he could side with conservative justices to erode the power of labor unions for government workers, give the upper hand to employers who want to prevent workers from banding together to complain about pay and workplace conditions, side with Texas in a dispute over electoral districts that were struck down by a lower court for being discriminating against black and Hispanic voters, limit state efforts to regulate anti-abortion pregnancy centers and uphold Trump’s ban on travel from several majority Muslim countries.

Kennedy’s vote also is likely to be decisive in two other high-profile issues, a Colorado baker’s objection to creating a wedding cake for a same-sex couple and efforts to rein in the drawing of electoral districts for partisan gain.

A retirement announcement could come at any time, and perhaps sooner rather than later if Kennedy is interested in the relatively quick and smooth confirmation of the next justice. Stevens and Justice David Souter, the last two retirees, revealed their intentions in April 2010 and May 2009, respectively. That enabled President Barack Obama to announce his choices in time for final Senate action by early August.

By contrast, in 1987, Powell waited until late June to say he was retiring. When the Senate voted down Robert Bork, Reagan’s first choice, and Douglas Ginsburg withdrew as Reagan’s second pick, the court began its next term with just eight justices on the bench. Kennedy, Reagan’s third choice, did not join them until February 1988.

The timing of his announcement also might influence the effective date of his retirement. The soonest Kennedy would leave is at the end of June, after all the court’s current cases have been decided. Some justices step down immediately. Others stay until their successor is confirmed, sometimes reflecting a worry that the court might start its term short-staffed.

Those concerns probably are not very serious at the moment because Republicans have every incentive and few procedural impediments to confirming a new justice. “I think it will be very difficult to defeat any Trump nominee for that seat unless of course there are character issues or that sort of thing,” said Richard Arenberg, a longtime Democratic Senate aide who now teaches political science at Brown University.

They probably would not want to chance waiting for the election results and the possibility of losing control of the Senate. Even in that circumstance, however, Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell still could push for a confirmation between the election and the start of the next Congress in January, Yalof said.

But if Kennedy decides to serve another a year or two and Democrats win the Senate in November, it could be considerably harder for Trump to get a nominee confirmed, especially since McConnell refused to act on Merrick Garland’s nomination in the last year of Obama’s presidency.

(AP)