Lawmakers in Greece voted Tuesday to limit the powers of Islamic courts operating in a border region that is home to a 100,000-strong Muslim minority, scrapping procedures dating back more than 90 years.

The proposed law passed easily, with backing from parliament’s largest political parties. It eliminates rules that referred many civil cases involving members of the Muslim community to Sharia law courts. Greek courts now will have priority in all cases.

The changes — considered long overdue by many Greek legal experts — follow a complaint a Muslim woman who lives in the northeastern Greek city of Komotini made to the Council of Europe’s Court of Human Rights over an inheritance dispute.

Legislation concerning minority rights was based on international treaties following wars in the aftermath of the Ottoman empire’s collapse. The Muslim minority in Greece is largely Turkish-speaking. Minority areas were visited last month by Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan.

Prime Minister Alexis Tsipras said in a statement that the new law respects the “special characteristics” of Greece’s Muslim minority, while redressing past injustices against community members “who were excluded from the legal guarantees and freedoms that all Greek citizens must enjoy.”

Greek governments in the past have been reluctant to amend minority rights, as many disputes between Greece and Turkey remain unresolved.

Currently, Islamic court hearings are presided over by a single official, a state-appointed Muslim cleric.

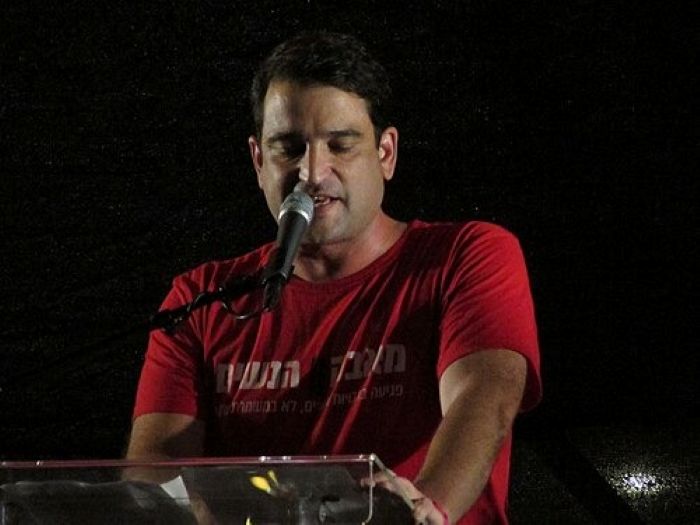

In parliament Tuesday, Constantine Gavroglou, minister of education and religious affairs, praised opposition party support for the bill. He said the current rules stemmed “from policies that were hostile toward the minority and sought to create second-class citizens.”

“This is not just a technical adjustment, it’s a very important day for parliament … because of the broad support that is key when addressing issues of democracy and people’s rights,” Gavroglou told lawmakers.

The extreme-right Golden Dawn party rejected the bill, arguing that it failed to adequately outline what powers would be retained by Islamic courts and did not address the issue of locally elected clerics who operate in an unofficial, but influential capacity.

(AP)