UV’nei Yisroel paru vayishr’tzu vayirbu vaya’atzmu bim’eod me’od vatimalei ha’aretz osam (1:7)

The Oznayim L’Torah recounts that a nonobservant Jew once approached his father-in-law Rav Eliezer Gordon, the Rav and Rosh Yeshiva of Telz in Europe. He argued that he although he believed whatever is explicitly written in the Torah, how could he, a modern and sophisticated intellectual, be expected to believe in apparently exaggerated Medrashim, such as Rashi’s comment that the Jewish women in Egypt miraculously gave birth to six children at a time?

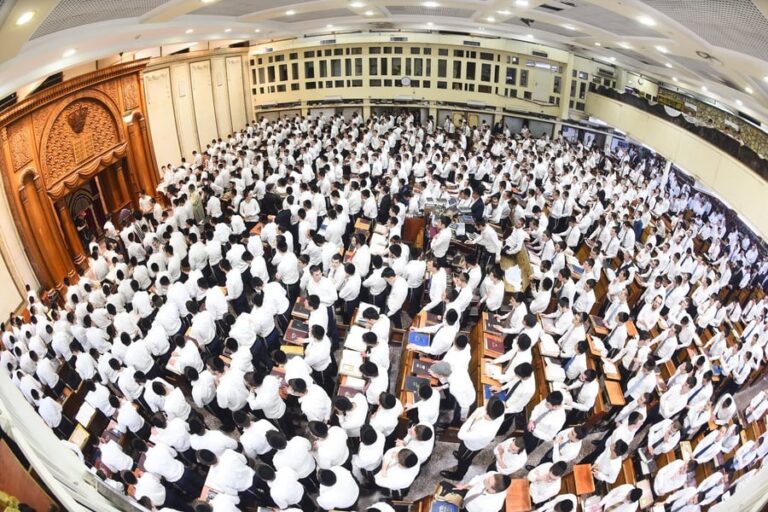

Without batting an eyelash, Rav Gordon answered him with a beautiful mathematical proof of the Medrash’s claim. In Parshas Bamidbar, the Torah (which the man claimed to believe in) records the results of the census conducted approximately one year after the Exodus from Egypt. The total number of first-born males was 22,273 (Bamidbar 3:43), and assuming that there were an equal number of first-born females, there were a total of 44,546 families.

The total number of men between the ages of 20 and 60 was 603,550 (Bamidbar 1:46), and doubling this number to account for the men under 20 and over 60 yields a total of 1,207,100 men. Assuming that there were an equal number of men and women results in a total of 2,414,200 Jewish people. Dividing 2,414,200 by 44,546 yields an average family size of approximately 54.

It takes a woman almost one year to conceive and give birth to a child. In those times, it took a woman two years after giving birth until she was able to conceive again (Niddah 9a), meaning that each child required roughly three years. A woman normally has 27-30 child-bearing years during her life. If each child takes three years, she will be able to give birth a maximum of 9-10 times during her lifetime. Dividing the 54 children the average woman had by the roughly nine times she gave birth yields a result of exactly six children per delivery, a proof which left the nonobservant Jew stunned and speechless.

Va’teireh es ha’teiva b’soch ha’suf vatishlach es amasah vatikacheha (2:5)

Upon descending to the river, Pharaoh’s daughter heard a crying infant and wanted to assist him and remove him from the river. However, the basket containing the crying Moshe was far away from her, and it was impossible for her to reach it. Nevertheless, Rashi writes that she stretched out her hand, which miraculously extended until it reached Moshe’s basket and pulled him toward her. The actions of Pharaoh’s daughter are difficult to understand. Although Hashem miraculously assisted her, she had no way of knowing in advance that this would occur. If she recognized that the basket was so far beyond her grasp, why did she even try to reach it?

The Chofetz Chaim explains that when faced with such an impossible situation, the average person would give up without even trying. Any attempted rescue would be viewed as a waste of time and effort. However, if this same person has a child trapped in a burning house or under a heavy object, he won’t think twice before attempting a miraculous rescue, which will indeed often be successful.

Similarly, Pharaoh’s daughter had a burning desire to save the crying infant. While she realized that the basket was beyond her natural reach, she also understood that Hashem only expects a person to do his best. At that point nothing more can be demanded of him, as he has put in his maximum efforts and the actual results are up to Hashem. In the case of Pharaoh’s daughter, she merited a miracle and the entire salvation of the Jews from Egypt can be traced back to her willingness to give it her all even in what seemed to be an impossible situation.

The following story depicts a modern-day application of this principle. Rav Don Segal once met a taxi driver who had merited driving the Steipler as a passenger. The driver related that the Steipler asked him if he studies Torah. The driver replied that although he regularly attends a shiur (class) in his neighborhood, he consistently falls asleep in the first minute of the shiur due to his sheer exhaustion.

The Steipler told him that in Heaven he is considered a great man, as Hashem only asks for a person’s best efforts. If the driver doesn’t have the energy to remain awake during the shiur, he will still receive tremendous reward for using his last remaining strength to travel to learn what little he is able to absorb before dozing off. Many times a situation seems desperate and beyond our control. At those times, we should take comfort in the lesson of Pharaoh’s daughter that all Hashem wants is our best good-faith effort, and at that point we can leave the rest to Him.

Vayomer Paroh mi Hashem asher eshma b’kolo lishloach es Yisroel lo yadati es Hashem (5:2)

The Darkei Mussar notes the striking contrast in Pharaoh’s actions over the span of just a few short years. In Parshas Mikeitz, the idolatrous Pharaoh had no problem accepting Yosef’s interpretations and recommendations, even though Yosef made it clear that his explanations emanated from Hashem. Yet a short while later, the Pharaoh who enslaved the Jews had completely forgotten Hashem’s existence and all of the benefits that his country had received through Yosef, challenging Moshe, “Who is Hashem that I should listen to His command that I free the Jewish slaves? I don’t know or recognize Hashem.” As both Pharaohs were idolaters at their core, what could account for this drastic change in attitude?

There was once a wealthy businessman whose associates received word that his entire inventory had been lost at sea. Unsure about how to inform him, they went for guidance to the local Rav, who volunteered to break the news himself. The Rav called in the businessman and engaged him in a lengthy discussion about trust in Hashem, as well as the insignificance of temporal, earthly possessions relative to the infinite, eternal reward of the World to Come.

At this point, the Rav asked the man what would happen if he were to receive word that his entire fleet had sunk in the ocean. The merchant, inspired by the insightful words of the Rav, answered that he could accept such a turn of events. Assuming that his plan had worked, the Rav informed him that this had actually occurred. Much to the Rav’s surprise, the man promptly fainted. After awakening the businessman, the Rav pressed him for an explanation. The man replied, “It’s much easier to have faith and trust in a G-d Who could wipe out my possessions than in One Who actually did.”

Both Pharaohs were idolaters to the core who never truly believed in Hashem. Nevertheless, it was much easier for the first Pharaoh to “believe” in a Hashem Who sent His agent (Yosef) to bring him satiety and riches than in for the second Pharaoh to believe in a Hashem Who sent His agent (Moshe) to order him to free millions of slaves.

The Medrash says that Hashem figuratively rides over the righteous, as the Torah states (Bereishis 28:13) regarding Yaakov that Hashem was standing over him. The wicked, on the other hand, view themselves as superior to their gods, as the Torah records (Bereishis 41:1) that Pharaoh dreamed that he was standing over the Nile river (which was one of the Egyptian idols). When we recite Shema twice daily and accept upon ourselves the yoke of Heaven, we should focus on genuinely placing Hashem above us and truly accepting His will, whatever it may be.

Answers to the weekly Points to Ponder are now available!

To receive the full version with answers email the author at [email protected].

Parsha Points to Ponder (and sources which discuss them):

1) Rashi writes (1:7) that the women in Egypt miraculously gave birth to sextuplets with each pregnancy. Who else in Tanach also had sextuplets? (Rashi Shmuel 2 6:11)

2) Rashi writes (2:7) that Moshe’s refusal to nurse from an Egyptian woman was due to his unwillingness to drink milk from a non-Jew with the same mouth that was destined to speak directly to Hashem. If a non-Jewish woman eats only kosher food, does nursing from her still cause the same spiritual impurity? (Rema Yoreh Deah 81:7, Meromei Sadeh Sotah 12b, Ben Ish Chai Parshas Emor 14, Chavatzeles HaSharon, Bishvilei HaParsha)

3) Rashi writes (4:24) that an angel sought to kill Moshe because of his negligence in circumcising his son. The Targum Yonason ben Uziel explains that Moshe didn’t do so because his father-in-law Yisro wouldn’t allow him to do so, as the Medrash teaches (Yalkut Shimoni 169) that Yisro and Moshe had agreed that Moshe’s first child should be an idolater. Why did Yisro desire or even suggest such an arrangement when Rashi writes (2:16) that he himself had already abandoned his idolatrous practices? (Taima D’Kra)

4) Why did Tzipporah use a stone to circumcise her son instead of a metal instrument, as we are accustomed to use today? (Perisha Yoreh Deah 264:7)

© 2010 by Oizer Alport.