In a presidential campaign where candidates are jockeying to be champions of the middle class and asking wealthy people for money, the problems facing the poor are inching into the debate.

In a presidential campaign where candidates are jockeying to be champions of the middle class and asking wealthy people for money, the problems facing the poor are inching into the debate.

Tensions in places such as Baltimore and Ferguson, Missouri, have prompted candidates to explore the complicated relationship between poor communities and the police, and the deep-seated issues that have trapped many of the 45 million people who live in poverty in the United States.

But addressing the long-running economic, education and security troubles in underprivileged neighborhoods is a challenge with few easily agreed upon solutions.

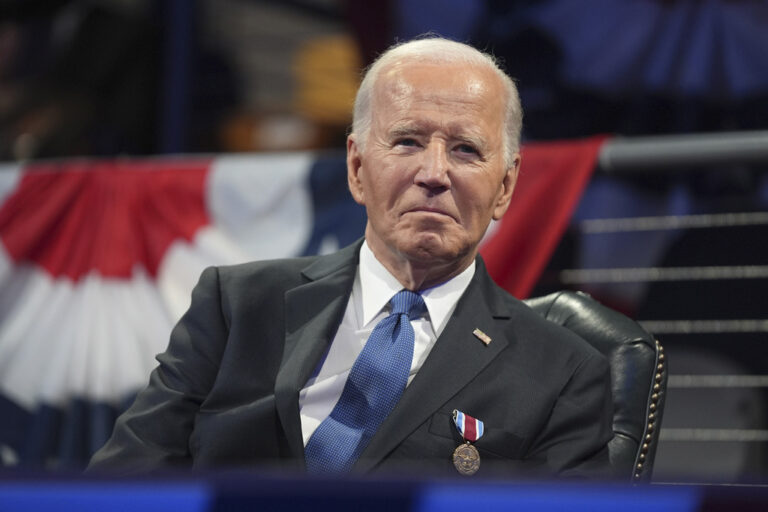

A frustrated President Barack Obama challenged the nation to do “some soul-searching” after riots in Baltimore followed the death of 25-year-old Freddie Gray in police custody. There have been other deadly altercations between police and black men or boys in Ferguson, New York’s Staten Island, Cleveland and North Charleston, South Carolina.

“I’m under no illusion that out of this Congress we’re going to get massive investments in urban communities,” Obama said. “But if we really want to solve the problem, if our society really wanted to solve the problem, we could.”

To some of the Republicans running to replace Obama, his call for spending more money in poor areas underscores the problem with many current anti-poverty programs. The GOP largely opposes new domestic spending and party officials often say federally run programs are bloated and inefficient.

“At what point do you have to conclude that the top-down government poverty programs have failed?” said Jeb Bush, the former Florida governor and expected presidential candidate. “I think we need to be engaged in this debate as conservatives and say that there’s a bottom-up approach.”

Republicans have struggled in recent years to overcome the perception that the party has little interest in the plight of the poor.

Mitt Romney, the GOP presidential nominee in 2012, was criticized for saying he was “not concerned about the very poor” and that it was not his job to worry about the 47 percent of Americans who he said “believe that government has a responsibility to care for them.”

More than 60 percent of voters who made less than $30,000 per year backed Obama over Romney in that campaign, according to exit polls.

Blacks and Hispanics, who overwhelmingly backed Obama in the past two presidential elections, are most likely to be poor. According to the census, about 27 percent of blacks and 25 percent of Hispanics were poor in 2012, compared with 12.7 percent of whites.

Bush has been among the most vocal Republicans discussing the need to lift the poor out of poverty and reduce income inequality, though he has yet to flesh out many of his policy proposals. He has been most specific about the need for greater educational choices and opportunities. Bush frequently cites his work in Florida, where he expanded charter schools, backed voucher programs and promoted high testing standards.

Kentucky Republican Sen. Rand Paul has long called for overhauling criminal sentencing procedures that he says disproportionately imprison low-income black men. He has promoted “economic freedom zones” where taxes would be lowered in areas with high long-term unemployment in order to stimulate growth and development.

Paul, who has made a point of reaching out to black communities, has drawn criticism for comments he made during the Baltimore unrest. In a radio interview, Paul said he had been on a train that went through the city and was “glad the train didn’t stop.”

Sen. Marco Rubio of Florida also has talked frequently about the poor. His anti-poverty proposals include consolidating many federal programs to help the poor into a “flex fund” that states would then manage.

Democrats, too, are trying to incorporate plans for tackling poverty into economic campaign messages that otherwise center on the middle class.

Following the Baltimore turmoil, Hillary Rodham Clinton made a plea for criminal justice changes that could aid urban communities. Among her ideas: equipping every police department with body cameras for officers. She said the unrest was a “symptom, not a cause” of what ails poor communities and she called for a broader discussion of the issues.

Former Maryland Gov. Martin O’Malley, who is expected to challenge Clinton for the Democratic nomination, has been at the center of the discussions about Baltimore’s issues. He was mayor from 1999 to 2007 and enacted tough-on-crime policies.

While O’Malley is not backing away from those practices, he is trying to put criminal justice issues in a larger context. He wrote in an op-ed that the problem in Baltimore and elsewhere is as much about policing and race as it has about “declining wages and the lack of opportunity in our country today.”

In some places that have dealt with recent unrest, residents say they welcome the campaign discussions on poverty and policing, but hope the issues will not fade away when the next big campaign focus arises.

“Hopefully these protests are something they’ll wrap themselves around, and we can make sure these issues get addressed,” said Thavy Bullis, a Baltimore college student.

(AP)