YWN regrets to inform, you of the Petira of HaRav Yaakov Moshe Magid ZAZTAL of Montreal.

YWN regrets to inform, you of the Petira of HaRav Yaakov Moshe Magid ZAZTAL of Montreal.

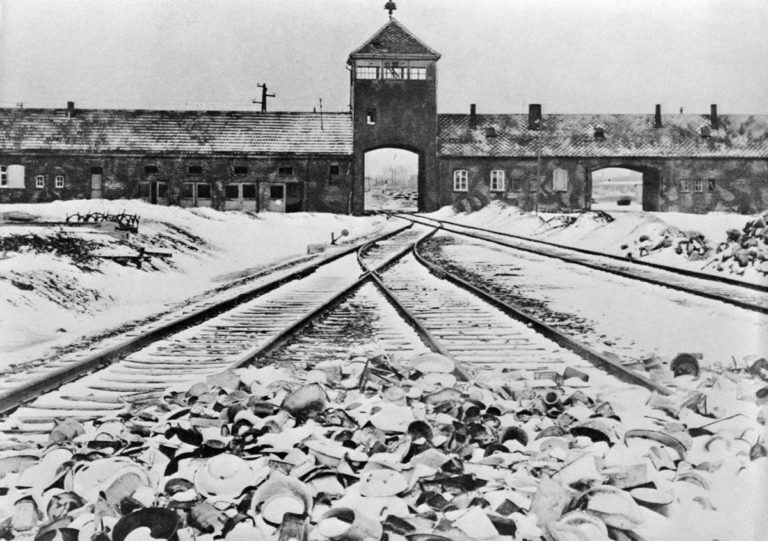

Rav Magid was one of the few remaining “Alter Mirrer”, the title given to those who studied in the Mirrer Yeshiva in Poland, and who survived the hands of the Nazis YM”S by fleeing with the entire Yeshiva through Siberia to Kobe, Japan, and on to Shanghai, China.

He lived until recently in Montreal. He passed away in Toronto at the home of his son Rev Hershel.

The Levaya took place on Sunday at Yeshiva Gedolah Zichron Shmayahu in Toronto.

The following first appeared in MIshpacha Magazine, and is being posted with their permission:

I enter his home and see that the definitive work on the history of the Mirrer Yeshiva and their miraculous escape, Hazericha B’pa’asei Kedem, is open on the table. The well-thumbed book is open to the page that lists the talmidim according to their places of birth, and Rav Magid indicates the page that lists the yelidei Breinsk, his own hometown. His voice is a gentle, sad sing-song as he reads the names of his childhood friends- Hashem yinkom damam.

He indicates a picture. ‘This is Avraham Arbus, an exceptional bochur. He was niftar in Shanghai from an illness.’ He pauses, and it’s clear that sixty-five years haven’t dulled the pain. ‘And here, in the middle of the picture, is Rav Shmuel Charkover, later a Rosh Yeshiva in Beis Hatalmud in Bensonhurst. What does this picture tell you?’

Rav Shmuel is smiling, surrounded by smiling bochurim.

Rav Magid answers his own question with another question. ‘What was there to smile about in Shanghai? Each and every one of us had lost loved ones, parents, siblings, and lived with a constant uncertainty about our own futures, if we would ever see a new world. It was brutally hot and there was nothing to eat. How could we smile?’

‘The answer is that there were older bochurim like Reb Shmuel, who was so accomplished in his learning and mussar that even then, we knew he was a gadol. He would gather all of us, the younger bochurim, around him and would give us chizuk. He laughed with us and cried with us, chatted about this and that and gave us hope that things would, one day, return to normal.’

‘That’s what you see in this picture!’

I ask Rav Magid about an extraordinary historical fact; those difficult, lonely years in Shanghai were also years of spiritual abundance, with unparalleled hasmada and growth among the talmidim. How could that be?

‘It was the people, the leaders, the gedolei olam that we had at our head, who inspired us to such great heights.’

Rav Magid shares some history with me. ‘The Yeshiva was divided in to two groups, the older bochurim and the younger bochurim, which I referred to as the ‘bayis rishon’ and the ‘bayis shaini’. The difference between the two chaburos was that the older group had learned by the Mashgiach, Rav Yeruchom Levovitz, and lived with the memory of his shmuessen. When Rav Yeruchom passed away, the Rosh Yeshiva, Rav Leizer Yudel Finkel, implored Rav Chatzkel Levenstein, who had moved to Eretz Yisroel, to return to serve as Mashgiach. The older group, Rav Yeruchom’s talmidim, respected the new Mashgiach, but we, the newcomers, were completely in awe of him. He was a malach and we revered him. The older talmidim gathered around Rav Leib Malin at that time, the prime disciple of Rav Yerucham. In Shanghai, however, even they, the bayis rishon, were witness to the open miracles that surrounded Rav Chatzkel, and they too learned to revere him.’

I ask Rav Magid what sort of miracles. He shares a story. ‘There was a group of talmidim in the Yeshiva from Germany, and for these bochurim to learn in the Mir, which represented different ideals and values than that of German Jewry, represented a form of mesiras nefesh. One of the lions of that group was Binyamin Zeilberger, who learned with tremendous diligence and passion and was well-respected in the Yeshiva.’

‘One Yom Kippur he took ill, and as the day progressed, his condition worsened, to the point that we feared for his life. Shortly before neilah, someone returned to the Beis Medrash from a visit to Binyamin with the news that his life was in danger.’

‘Now you have to understand what Rav Chatzkel was like on Yom Kippur; his shacharis Shemoneh Esrei would continue until krias haTorah, when he would receive the aliyah of Levi. His amida of mussaf would last until mincha and his mincha until neilah. Thus, by the time the holy tefillah of neilah arrived, the Mashgiach would have been on his feet, in silent prayer, the entire day.

As our friend, Binyomin Zeilberger, hovered near death, our thoughts were with him. We prepared to daven neilah with renewed concentration, ready to storm heavens for this budding talmid chacham.

At that holy hour, the climax of the holy day, rays of a setting sun filtering in through the windows, the angelic figure of the Mashgiach suddenly headed towards the Aron Kodesh. He ascended the steps and opened the paroches, then he burst into weeping- the simple, trusting cries of a child entreating his father.

‘Tatte zisse’ we heard him say in a tone that made it clear that he felt the Ribbono shel Olam’s presence acutely. ‘The Gemara says that one defending angel, one z’chus, is sufficient to have You tear up a judgment. Binyomin came here from Germany to learn and persevered despite many obstacles to toil in learning.’

‘Ribbono shel Olam! Does Binyomin not have one malach to judge him favorably? He who invested such energy and heart to becoming what he is, does he not have one z’chus to counter the evil decree?’

The Mashgiach descended from the Aron Kodesh and, in the waning minutes of the day, we lost ourselves in prayer, charged and invigorated by the conversation we had just overheard.’

‘On Motzoei Yom Kippur we were greeted by the joyous sight of our friend’s face slowly regaining its color. Within days he had returned to full strength and took his place at the top of the Yeshiva…’

*****

I am anxious to take Rav Magid back to the prewar years, his own youth. As a child, just before Bar Mitzvah, his father, Reb Elchanan Dovid, sent him to learn in Grodno, the Yeshiva of Rav Shimon Shkop. ‘My father was a tremendous person, a talmid chacham and tzaddik.’ Rav Magid shows me a sefer, Chonoh Dovid, that his father authored on Mesechta Chulin. ‘He wrote this without any readily available sefarim, just a Gemara; I wasn’t privileged to know him, since he sent me off at such a young age. During the five years that I was in Grodno, I visited my parents only three times, and then I went to Mir.’

‘This sefer, Chonoh Dovid, was really a manuscript on the whole Mesechta, but the last time I visited him, I really wanted something tangible to stay connected. I ‘borrowed’ the notes on the first perek…and that’s why we have this sefer. The rest is lost forever. I carried this manuscript with me for years, and when I arrived here- in Montreal- and got married, I took the first money I could get my hands on and used it to print this.’

I ask Rav Magid why his father had to send him away at such a young age; were there no Yeshivos in Breinsk? ‘There were, but in addition to Yeshivos, there was also something else; constant hunger and poverty. It was that grinding poverty that ultimately led to a revolution on traditional Yiddishkeit; communism, socialism, Yiddishism. My father understood that the nisayon of aniyus is such that it makes every other option seem more enticing, and the various parties and events held by the various different factions in town- none of them faithful to Torah living- worried my father and he knew that a real Yeshiva environment, with no distractions, was necessary for me. There was a bochur in Breinsk named Sholom Levin, and he learned in Grodno, so my father sent me with him; he struggled to find money for travelling expenses, and he certainly had no money for me to take along. I arrived there penniless and very frightened.’

‘It was Cheshvan of 1934, and I was very young, not yet bar mitzvah.’

I ask Rav Magid how he celebrated his bar mitzvah in Yeshiva. He laughs heartily. ‘Celebrate? I got an aliyah and that was it.’

I ask about the personalities of Grodno, if he had an encounters with Grodno’s famed Rosh Yeshiva, Rav Shimon Shkop. ‘Rav Shimon was Rosh Yeshiva of the older bochurim, I had little connection with him. I did once have a nice experience with his son, Rav Moshe Mordechai, the Rov of the town. I used to like to learn in a small shul- an ancient building, maybe four hundred years old- by myself. One day I was learning there and there was another Jew learning there as well. It was just the two of us.’

‘When he finished learning, he closed his Gemara, and suddenly he jumped up. ‘My watch, my watch!’ he shouted, ‘you stole my watch’ It turned out that he had removed his watch while he was learning, and it was missing. He immediately assumed that I- the only other person in the room- was the culprit, and despite my protests, he insisted on taking me to a din Torah. We went to the home of the Rov who listened to his charges. The Rov pulled out one sefer, then another. He looked into the Shulchan Aruch, and then into the nosei keilim. Only after a few minutes of research, did he turn to the litigant.’

‘There is nothing you can do,’ the Rov told him. ‘I feel badly, but you have no ta’aneh.’

‘The fellow left; he may have lost his watch, but at least he felt like the Rov had tried to help him.’

‘I always retell that story to poskim and morei hora’ah; it’s important to make the questioner feel like his question is a good one, otherwise he will refrain from asking the next time.’

‘There was a Rov in Grodno that noticed me, a cute little boy, and would look out for me. When I was particularly hungry, or in need of a kind word, I would go daven in the large shul- Chevra Sha’s- where he was Rov. He would always slip me a few coins and arrange suitable meals for me. His name was Rav Michel Dovid Rozovsky, father of the Ponevezher Rosh Yeshiva, Rav Shmuel, and until today, I remember his kindness.’

‘I was in Grodno for Pesach- lacking the funds to go home- and entered the large shul on the Leil Haseder, feeling homesick and sad. I couldn’t help but think of Pesach back in Breinsk and the warmth of my dear family, where I’d felt like a little prince. Here I was, alone, on Yom Tov, in a strange city.

‘Suddenly, the Rov looked at me from the front of the room and called me outside. He reached in to his pocket and pulled out a handkerchief. From within it, he withdrew a large piece of egg matzah. He stroked my cheek. ‘Yankele,’ he said, ‘go and eat something quickly before davening, in order that you may have strength to get through the seder tonight.’ He took me back in and arranged an invitation for me at the home of a prominent local- Reb Yisroel Dunski was his name- and I went back in to daven with a joyous heart.’

Rav Magid pauses, and as usual, has a mussar lesson to share. ‘I always say, that was a Jew vos tracht vegen yenem, who thought about others!’

‘Many years later, in 1966, I went to Eretz Yisroel for the first time in my life, and I visited Rav Shmuel Rozovsky. I shared this story with him and he grew very emotional. ’If you came all the way to Eretz Yisroel just to share that with me, it’s already worth it,’ he said.

**************

From Grodno, Rav Magid went to learn in Mir, and he arrived there on the eve of the war, in 1938. Winds of upheaval were already blowing, but inside the beis medrash, the atmosphere was one of diligence and intensity.

I ask Rav Magid about the figures of those years, the illustrious Gedolim that distinguished themselves during those trying times. Of course, he mentions Rav Chaim Ozer. ‘It was Rav Chaim Ozer who emerged as the central figure in our lives, the father of the Yeshivos in every sense. He sacrificed his time, his learning, his energy; everything, to help b’nei Torah. Sometimes it was with money, sometimes with documents, and sometimes with words of chizuk, but his door was always open.’

‘In a sense, when he was niftar, we knew that it was the end, it was as if the last remaining shield was removed from in front of us.’

Rav Magid shares a poignant memory. ‘Rav Chaim Ozer was niftar on a Friday, the 5th day of Av, and we were inconsolable. We felt that the hands that had been carrying us all were no longer there.’

‘That night, Leil Shabbos, a group of us Yeshiva bochurim, decided to go to the tish of the Modzitzer Rebbe, who had also escaped to Vilna. The loss of the gadol hador was on everyone’s minds, and the Rebbe referred to it by the tish.’

‘It was Parshas Va’eschanan, and the Rebbe quoted the first passuk in the parsha; ‘Va’eschanan el Hashem bo’eiss hahi.’

He mentioned the perpetual disagreement between Klal Yisroel and Hakadosh Boruch Hu. The Yidden say ‘Hashiveinu Hashem elecha venashuva, return us to You, Hashem, and then we will do teshuva, meaning that Hashem should make the first move. Hashem, in turn, says ‘shuva elai v’ashuva aleichem, return to Me, and then I will return to you, that we should make the first move.’

Rav Magid recalls. ‘The Rebbe, in a pained voice, cried out ‘Moshe Rabbeinu saw far into the future that there would be terrible times for the Yidden, periods of darkness and pain, and he prayed for the Yidden that would struggle to maintain their faith in those trying times; Va’eschanan el Hashem bo’eiss hahi- I davened to Hashem for ‘that time’- Moshe davened for us- and what did he ask?’

The Rebbe continued with the end of the passuk. ‘Hashem Elokim, Ata hachilosa, – Hashem, please, You be the one to start the process of teshuva and draw the Yidden close.’

‘That was the Rebbe’s Torah on that bitter Friday night!’

I jokingly comment that, as impressed as the bochurim were by the Rebbe’s powerful message, it obviously wasn’t enough to turn them in to chassidim.

Rav Magid looks at me in shock. ‘You think that was our only connection with chassidus? Throughout the years in Shanghai, the Amshinover Rebbe was a central figure in our lives. We would attend his tish and speak with him frequently.’

Rav Magid smiles at a memory. ‘He took one of our best bochurim, Reb Chaim Milikovsky (father of the present Amshinover Rebbe of Bayit Vegan) as a son-in-law.’

Rav Magid shares a great story. ‘When the Rebbe took a ‘litvishe’ bochur as a son-in-law, some of his chassidishe friends ‘tcheppet’ him about it. ‘A bochur without a beard?’

‘The Rebbe replied, ‘for the others to get what my Chaim’l has would take them twenty years- for him to get what they have (a beard), will take him a few months!”

‘Do you remember the chasunah?’ I ask.

‘Remember? I held one of the poles at the chuppah. Of course I remember! The Rebbe was mesader kiddushin, and just before he performed the ceremony, he called out ‘Chaim’l, gib a kuk oiff di kallah, take a look at the kallah.’ (A reference to the halacha that one cannot a marry he has not yet seen).

Rav Magid shares a humorous story with me. ‘Just a few years back, my friend Rav Shmuel Birnbaum, the Rosh Yeshiva of Mir- Brooklyn, was here, in Montreal, for a chasunah, and was mesader kiddushin. Under the chuppah, just before making the bracha, he instructed the chassan to take a look at the kallah. After the chuppah, I asked Rav Shmuel ‘do you think that you’re the Amshinover Rebbe?’ How he laughed!”

***********

What makes the conversation with Rav Magid so enjoyable? Perhaps the answer lies in a story he himself shares.

It was that Elul of 1939- the last vestige of calm before the storm. War had broken out, and everywhere, parents reached out their arms wide to pull their children close. Young Yankel Magid, the boy who had been away from home since before his bar mitzvah and barely knew his own father, was actually home. What good fortune!

But, no, his father decided otherwise. He called in his teenage son and told him that, as much as he yearned to have him close by, ‘dein platz iz mit di Yeshiva -vos vet zein mit de Yeshiva vet zein mit eich. Your place is with the Yeshiva. Whatever fate will meet the Yeshiva, will be yours as well.’

With tears in their eyes, his parents bade him farewell, encouraging him to leave them and return to his place- the Yeshiva- realizing full well that they might never see him again.

They didn’t, in fact, but they did save his life with that remarkable act of self-sacrifice.

For his Yeshiva- the Mirrer Yeshiva- was lifted on eagle’s wings and carried to safety, a fate unique in the world of Yeshivos, and Yankel, whose place was with that Yeshiva, merited that exceptional salvation.

So even now, when he speaks- though well over half- a century has passed, a new world has arisen- one in which his own children have taken a prominent role as Roshei Yeshiva and marbitzei Torah in the olam haYeshivos- Rav Magid hasn’t forgotten those instructions; he speaks not of history, not of times and places gone by, but rather of his place, the Yeshiva. Just like his father said.

15 Responses

Beutiful peace.

I knew Rav Maggid well. He exhibited the same self sacrifice as his parents. Years ago there were no high quality yeshivos in Montreal. So he sent his oldest son away from home at the age of 14 to New York to learn by the “Alte Mirrer” of Mir and Beis Hatalmud. His children are all great talmidei chachomim

We must learn to focus on the future instead of the past.

Let’s worry more on the well-being and Parnoso of our children, instead of the stories of Shangai.

BDE, the Alter Mirrer did not go through Siberia, they went from Lithiania with visas from the legendary Sugihara to Vladivostok and then to Kobe and then Shanghai. From 325 talmidim, today there is less than a minyan left

This piece is hafla v’feilo. Anyone who reads it and doesn’t immediately think, “Oy, I don’t rise to the shoelaces of those tzaddikim”, has no neshoma. Thank you, YWN, for posting it.

oy. “ader says: February 3, 2015 at 12:59 am” such a complicated “asher karcha baderech” cold amalekdig response to such a heilige poshite article.

Frum yidden look to the simple past and see the only way through the complicated present and to Hashem’s desired future.

Let Hashem, “hazan es hakol” worry about your parnassah.

You worry about bringing up your pikadon’s to be like this groisser mentch.

Thank you very much, YWN

BDE

#5

R’ Aharon Kreizer zt”l was greeted once by Rav Gifter zt”l with an exuberant “sholom aleichem an ‘amolidiker yid’ “.

R’ Aharon responded with a shrug and reply “mir lernen toireh in Amerikeh oichet”

Dear Ader

The greatness of the Jewish People is that we focus on both.That is symbolized by kosher animals both chewing cud and having split hooves.We need the past to focus on the future.Besides there are a plethora of YWN articles pertaining to future needs in general and the specific one you mentioned.

Would be interested to know about the last remaining Alte-Mirrers

To Ader #3

You happen to be right on.

There are people that are busy all day telling stories of how close they were to Groiseh Rebbeh’s and Roshei Yeshivos, while there children and grand children are struggling with Parnosoh & horrible personal debts.

to #10, you are absolutely correct. In fact there are people who tell stories about the Yankees, whose children suffer the same fate. There are people who tell stories about grocery markets, whose offspring suffer terribly. There are people who revel in When zeidy was young classics whose children are impoverished, and unbelievably, there are those who prefer dickens who are in the same boat. Basically, great point.

to 11

It all depends whether people are telling those stories for self-aggrandizement.

Common sense, nobody can claim that they are living the perfect unblemished life, when their children are struggling.

Yes, #10 is right.

@Yira – “you HAPPEN to be right” One doesn’t happen to be right. One works hard, toils in Torah, is m’shamesh Talmidei Chachomim, asks sh’eilos, and with siyata di’Shmaya will be shown what’s right. Happening upon what’s right, happening upon anything, resorts everything to happenstance to mikreh. That is the outlook of Amalek; “asher karcha ba’derech”. “Kol asher karahu”

To 13

The way to be Loichem against Amalek, is by “Tzei Hilochem B’amolek MOCHOR” and “Ki Mocho EMCHE”. Everything is Loshon L’habboh.

Don’t get stuck to stories of the past. Think about the well-being and Parnosoh and finances of the future children and grand-children.

It’s hard to believe that some of you would be willing to use the commenting section to aggrandize your personal objectives. This article is about the petira of a Talmid Chochum. When someone dies it is expected to be maspid him. A hespid is telling over positive things from the nifter’s past to 1) realize our loss and 2) to learn from for our future actions.

Some of you have unfortunately missed the boat. Very Sad!