American Jews who fled their Syrian homeland decades ago went to the White House this week to appeal to the Trump administration to lift sanctions on Syria that they say are blocking them from restoring some of the world’s oldest synagogues and rebuilding the country’s decimated Jewish community.

For Henry Hamra, who fled Damascus as a teenager with his family in the 1990s, the 30 years since have been shadowed by worry for what they left behind.

“I was just on the lookout the whole time. The old synagogues, the old cemetery, what’s going on, who’s taking care of it?’ said Hamra, whose family has settled in New York.

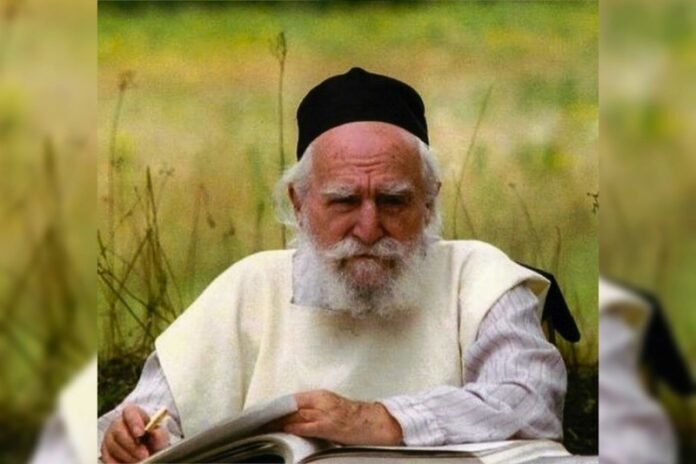

His family fled the Syrian capital to escape the repressive government of Hafez Assad. With the toppling of his son, Bashar Assad, in December and the end of Assad family rule, Hamra, his 77-year-old father, Rabbi Yusuf Hamra, and a small group of other Jews and non-Jews returned to Syria last month for the first time.

They briefed State Department officials for the region last week and officials at the White House on Wednesday. The White House did not immediately respond to a request for comment.

They were accompanied by Mouaz Moustafa, executive director of a group called the Syrian Emergency Task Force, who was influential in the past in moving U.S. officials to sanction the Assad government over its institutionalized torture and killings.

With Assad gone and the country trying to move out of poverty, Moustafa has been urging U.S. policymakers to lift sweeping sanctions that block most investment and business dealings in Syria.

“If you want a stable and safe Syria … even if it’s as simple as rebuilding the oldest synagogue in the world, the only person that’s able to make that a reality today is, frankly, Donald Trump,” Moustafa said.

Syria’s Jewish community is one of the world’s oldest, dating its history back to the prophet Elijah’s time in Damascus nearly 3,000 years ago. It once had been one of the world’s largest, and was still estimated at 100,000 at the start of the 20th century.

Increased restrictions, surveillance and tensions after the creation of Israel and under the authoritarian Assad family sent tens of thousands fleeing in the 1990s. Today, only seven Jews are known to remain in Damascus, most of them elderly.

What began as a largely peaceful uprising against the Assad family in 2011 grew into a vicious civil war, with a half-million dying as Russia and Iranian-backed militias fought to keep the Assads in power, and the Islamic State group imposing its rule on a wide swath of the country.

A U.S.-led military coalition routed the Islamic State by 2019. Successive U.S. administrations piled sanctions on Syria over the Assad government’s torture, imprisonment and killing of perceived opponents.

Bashar Assad was ousted in December by a coalition of rebel groups led by an Islamist insurgent, Ahmad al-Sharaa, who today leads what he says is a transition government. He and his supporters have taken pains to safeguard members of Syria’s many minority religious groups and pledged peaceful coexistence as they ask a skeptical international community to lift the crippling sanctions.

Although incidents of revenge and collective punishment have been far less widespread than expected, many in Syria’s minority communities — including Kurds, Christians, Druze and members of Assad’s Alawite sect — are concerned and not convinced by promises of inclusive government.

After the decades away, Yusuf Hamra’s former Christian neighbors in the old city of Damascus recognized him on his trip back last month and stopped to embrace him, and share gossip on old acquaintances. The Hamras prayed in the long-neglected al-Franj synagogue, where he used to serve as a rabbi.

His son, Henry Hamra, said he was shocked to see tiny children begging in the streets — a result, he said, of the sanctions.

Visiting the site of what had been Syria’s oldest synagogue of all, in the Jobar area of Damascus, Hamra found it in ruins from the war, with an ordnance shell still among the rubble.

Hamra had become acquainted with Moustafa, then a U.S.-based opposition activist, when he reached out to him during the war to see if he could do anything to rescue precious artifacts inside the Jobar synagogue as fighting raged around it.

A member of Moustafa’s group suffered a shrapnel wound trying, and a member of a Jobar neighborhood council was killed. Both men were Muslim. Despite their effort, fighting later destroyed most of the structure.

Hamra said Jews abroad want to be allowed to help restore their synagogues, their family homes and their schools in the capital’s old city. Someday, he says, Syria’s Jewish community could be like Morocco’s, thriving in a Muslim country again.

“My main goal is not to see my Jewish quarter, and my school, and my synagogue and everything fall apart,” Hamra said.

(AP)

2 Responses

Too soon. First see who that new Syrian leader really is.

Morocco’s Jews didn’t leave. No one is going to move back to Syria. Why rebuild?