by Rabbi Yair Hoffman

Today the 24th of Cheshvan is the Yahrtzeit of Rav Dovid Kviat zatzal, one of my Rebbeim. In honor of the yahrtzeit is some Torah that he said. May his neshama be a meilitz yosher for us all.

What happens when the doctor says that a sick person must eat something forbidden? Does he recite a bracha or not?

Many of us are familiar with the verse in Tehillin (10:3) “Botzea beireich ni’aitz Hashem — A thief who blesses blasphemes Hashem.” The Gemorah uses this verse to describe someone who blesses on stolen food. The Mishna Brurah (196:3), based on the Rambam and Poskim, rules that it is not only stolen food to which this verse can be applied — but also to someone who purposefully eats non-kosher food.

THE RAMBAM’S VIEW

The Rambam (1138-1204) in Hilchos Brachos 1:19 rules that one who eats any forbidden item , whether purposefully or in error, makes neither a beginning bracha nor an after-bracha.

THE RAAVAD’S VIEW

Interestingly enough, the Raavad (1125-1198) argues on this principle of the Rambam!

He writes that the Rambam made a great error here, and that the Gemorah in Brachos 45a only states that it is Zimun that is forbidden. But a beginning Bracha or an after-bracha – why shouldn’t they recite it? They are deriving hanaah – benefit!

EXPLAINING THE MACHLOKES

My Rebbe, Rav Dovid Kviat zatzal, a Rosh Yeshiva in Mirrer Brooklyn, one of the last of the Alter Mirrers – those who were in the Mirrer Yeshiva and travelled to China to remain throughout the war, provides the following explanation (see Sukas Dovid on Kesuvos 81a-82b):

It appears that they are arguing on the essential nature of what Chazal enacted a blessing upon. The Rambam holds that they enacted the blessing upon the hanaah – the benefit one receives from the [food] item. Therefore, since the food item is forbidden, and the benefit one receives from the food item is likewise forbidden – we do not recite a bracha. This is true even if it was beshogaig – by accident – because, at the end of the day, the benefit he received from the food item is forbidden to him.

The Raavad holds that the blessing was ordained upon the benefit he receives in being satiated, no longer hungry. That is the intestinal benefit, so to speak. Therefore, the fact that he is now full and no longer hungry is not, in its essence, forbidden. He would, therefore, recite a blessing. This is the Raavad’s intention when he writes, “But a beginning bracha or an after-bracha why shouldn’t they bless – since they benefitted?”

According to this explanation, even the Rambam would hold that a blessing would be recited regarding:

- A dangerously ill sick person who is required to eat something forbidden

- A dangerously ill person who is required to eat on Yom Kippur

The reason is that since in these cases it is permitted for him to eat in these circumstances, it is a permitted benefit, and the [food] item is considered like a chaifetz shel heter – a permitted item. The reason is that he is performing a Mitzvah – as the Torah states (Vayikra 18:5), “And you shall live by them” and he is obligated to eat. We see this indication in the words of the Shulchan Aruch (Siman 196) as well, where he rules like the Rambam, but also rules that one who is forced to eat on Yom Kippur must bless.

THE BACH’S VIEW

The Bach (1561-1640), however, in Siman 204, differentiates between the two cases. He writes that a dangerously ill person recites a blessing when he eats on Yom Kippur because the essential character of the eating is actually permitted. Whereas in regard to something non-kosher, the item itself is forbidden. The Bach thus holds that one DOES NOT RECITE A BLESSING when a doctor tells you to eat something non-kosher.

ANALYZING THE BACH

One must say that the Bach holds that the bracha comes on the actual item, because if you recite it on the benefit from the item – the benefit is fully permitted and he is actually fulfilled a Mitzvah since he is performing “v’chai bahem – and you shall live by them.”

The Shulchan Aruch’s view is that the bracha is recited on the han’aah – the benefit, and the benefit is fully permitted. Indeed, in Shulchan Aruch OC 204:9, the Mechaber (1488-1575) holds that a sick person who ate something forbidden must make a first bracha and an after-bracha.

Perhaps the issue is dependent upon the concept of whether the leniency of “VeChai Bahem” is that the prohibition is pushed aside (d’chuya) or permitted (hutrah). [See Teshuvas HaRashba #786, Rosh, end of Yuma]. If it was just pushed aside – then it would still be considered a prohibition and one would not recite a blessing. If it was made permitted (hutrah) then it would be considered an Item of a Mitzvah – and one would recite a blessing.

But this is not so clear, because, nonetheless, since the benefit is permitted – and he is performing a Mitzvah, then why should he not recite a blessing if the blessing is on the benefit? It would seem that the opinion of the Bach is more cogent if we say that the blessing is on the item itself.

THE TAZ’S VIEW

The Taz (OC 196:1) writes that one who by mistake eats something forbidden does make an after bracha, because it is like a dangerously ill person who recites a blessing on a forbidden food.

THE ARUCH HASHULCHAN’S QUESTION ON THE TAZ’S VIEW

The Aruch HaShulchan (OC 196:6) cites the Taz and disagrees with him. He writes that his words are quite strange, for regarding a shogaig, a mistaken eating, granted that he is not chayav for it – but at the end of the day, he did consume something forbidden and this is not within the confines of a bracha. But regarding a danger – he is eating something permitted, as the Torah permitted it to him. It is actually like completely permitted food, and how does one compare to the other?

RAV KVIAT ZT”L’s ANSWER FOR THE TAZ

It would appear that the Taz holds that in both cases, the food item itself is forbidden. Nonetheless, since he did not do an avairah – he is obligated to bless on his hana’ah – the benefit he received. When one makes a mistake, it is not considered a prohibition, and even though he needs a kaparah – an atonement even in a case of a mistake, regarding reciting a blessing we follow the gavrah – the person himself. Therefore, the whole time he did not violate an aveirah, he is obligated to recite a blessing on his hana’ah – even if the actual hana’ah is a forbidden one.

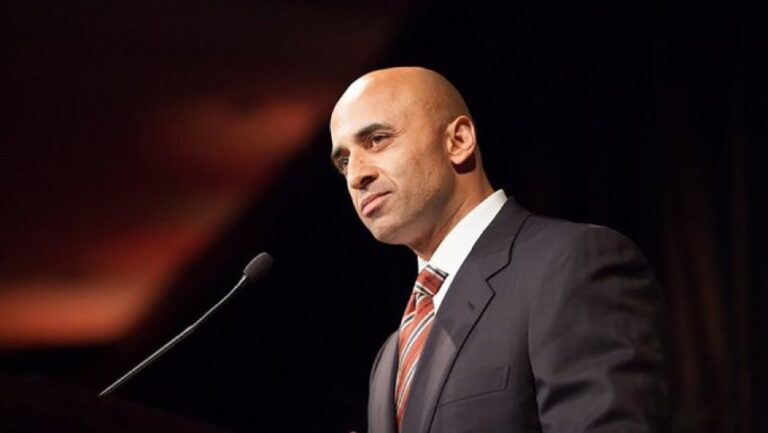

OVERVIEW OF RAV KVIAT ZT”L

Rav Dovid Kviat zt”l, a Slonimer Chassid, was also a Rosh Yeshiva’s Rosh Yeshiva. His Seforim were the first stop that Roshei Yeshiva and Maggidei Shiurim looked at when formulating their own shiurim.

He was a member of Agudas Yisroel’s Rabbinic Committee. He was Rosh Yeshiva in the Mirrer Yeshiva in Brooklyn. He was the Rav of the Agudah of 18th Avenue But mostly, Rebbe was a living, breathing embodiment of a Sefer Torah– personifying the highest ideals of Gadlus BaTorah, Yiras Shamayim, and Ahavas Yisroel.

Rav Kviat was a mechanech par excellence. Like Rav Elchonon Wasserman zatzal, he taught the first year Bais Midrash shiur. His remarkably cogent and precise explanations combined with his patient and loving demeanor were the ideal tools of a mechanech. His impact on his Talmidim was profound. Many went on to become Roshei Yeshiva and prodigious Talmidei Chachomim themselves.

Prior to the Rebbe’s appointment in the Mirrer Yeshiva in Brooklyn, Rav Chaim Shmulevitz zatzal had expressed his shock that Rav Kviat was not yet employed in a prominent Yeshiva in America. “What?” he said, “Reb Dovid was yet a Gadol HaDor while he was in Shanghai!”

The author can be reached at [email protected]