(By Dovid Margolin – Chabad.org)

At 11 p.m., Jacob Gabay stands leaning against a fence in Old Montefiore Cemetery. It’s dark outside and a little cold, but he has other things on his mind. Namely: Where is his daughter, Shani?

That’s all Jacob’s been able to think about since Oct. 7, when his daughter, Shani Gabay, 25, disappeared from the Nova rave at Kibbutz Re’im in southern Israel. “She is not captive. She is not dead,” the grizzled father says. “She is missing.”

Shani Gabay is one of the approximately 240 men, women and children kidnapped by Hamas terrorists and their Gazan collaborators on that terrible day. And Jacob is one of 170 family members of Israeli hostages presumed in Gaza who arrived in New York on Nov. 13 to visit and pray at the Ohel, the resting place of the Rebbe, Rabbi Menachem M. Schneerson Zt”l.

The chartered flight, organized by the Terror Victims Project of the Chabad Youth Organization—the umbrella arm of the Chabad-Lubavitch movement in Israel—came to New York for one purpose and one purpose only: to pray for a miracle at this holy site.

Gabay had emerged from the Ohel only moments earlier. “Here, I feel like I am close to G‑d,” he says resolutely. “I feel the power of this place in my bones.”

Gabay, who lives in the northern town of Yokneam Illit, near Haifa, is a believer in miracles. He’s seen them before. Exactly 20 years ago, when Shani was 5 years old, her eyesight began to fail, and doctors said she would soon be totally blind. While in the hospital with his daughter, someone gave him a card bearing a photo of the Rebbe on one side and the address of the Ohel on the other. Gabay placed it in his wallet and forgot about it. Later that year, he traveled to Texas, and on his way home to Israel had a stopover in New York. He opened his wallet, saw the card sitting inside and decided to come to the Ohel to pray. Soon after returning to Israel, Shani’s eyesight began to improve. Eventually, she was totally healed.

Which is why Gabay didn’t hesitate to join Chabad’s chartered plane to New York when he heard about it. The Chabad rabbi in Yokneam Illit had come to his home to help him put on tefillin and had just begun broaching the idea to him. “Even before he explained to me what exactly this was all about, I understood I had to go,” he says. “I was drawn here.”

Earlier that morning, Gabay and his fellow family members of hostages had taken off, together with Chabad of Israel staff, on a chartered plane from Ben-Gurion International Airport in Tel Aviv. Upon landing in New York they headed straight to the Ohel, where they were greeted on the street by hundreds of American well-wishers.

At a short program held at the Ohel visitors’ complex, words of welcome and inspiration were shared by Rabbi Yehuda Krinsky, a member of the Rebbe’s secretariat and chairman of Merkos L’Inyonei Chinuch and Machne Yisrael, Chabad’s respective educational and social-services arms; Rabbi Berel Lazar, chief rabbi of Russia; Rabbi Yisrael Deren, a longtime Chabad emissary in Connecticut; and Aviv Ezra, Acting Consul General of Israel in New York. Present, among others, was Rabbi Josef Aronov, chairman of the Chabad Youth Organization in Israel, who flew to New York together with the families, and Igor Tulchinsky, the Jewish philanthropist who funded the trip.

“Our days and our nights are focused in prayer, demanding that your loved ones—our loved ones—come home to you safe and sound, physically and spiritually,” Krinsky said, the crowd of onlookers and family members responding with a resounding amen, a word recited loudly and whispered quietly countless times over the duration of the evening.

The program also included songs of hope, such as “Ani Maamin” (“I Believe”), a Holocaust-era tune expressing the Jewish’s faith set to words adapted from the writings of the 12th-century philosopher and sage Maimonides, as well as a video of the Rebbe.

“A Jew is not—G‑d forbid—alone in exile, while G‑d is in His palace in the heavens, looking down from above at what is happening to the Jew below and blessing him from afar,” the Rebbe said in his 1984 talk. “ … The reality is that G‑d finds Himself wherever any single Jew finds himself. And when a Jew is in exile, ‘G‑d is with them!’ G‑d is there together with him, in that exile. And He’s not there as an outside observer, but rather: ‘In all of their sufferings, He suffers with them.’ … This allows us to appreciate the extent to which we have G‑d’s help to overcome all hardships, for He puts Himself, so to speak, into the same hardships.”

The program, however, was a mere prelude. Though the gathered family members represent every segment of Israeli society, from religious men and women with covered heads to secular kibbutzniks who seldom, if ever, attend synagogue, it was clear to any observer that the reason why they’d made the long trip to New York was to enter the Ohel itself. That they’d come to be in the presence of the Rebbe and to pour their hearts out in prayer at his holy resting place.

“Everyone feels that we’re at a point where only G‑d can help, that we need a miracle,” explains one of the trip’s leaders, Rabbi Asi Spiegel of the Chabad Youth Organization of Israel. “That’s why we’re here, why these families came here. There is a universal understanding that this is a place where darkness is illuminated.”

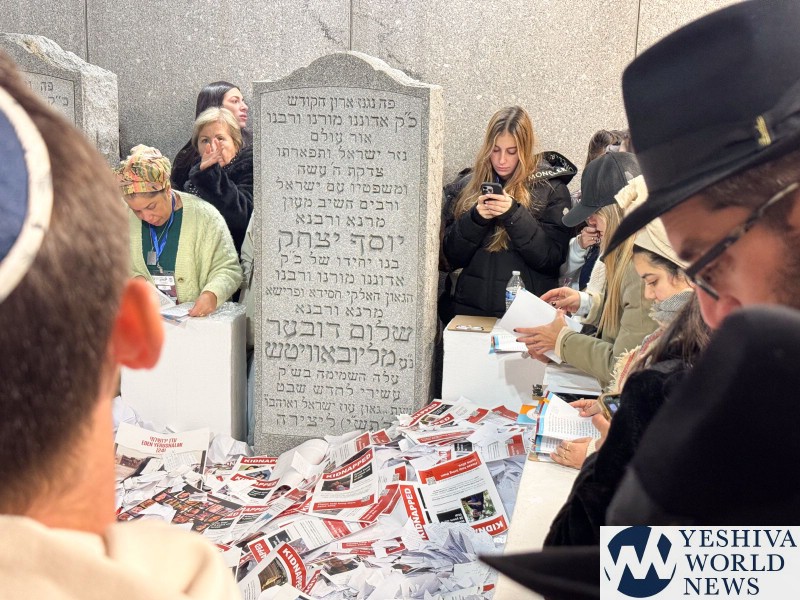

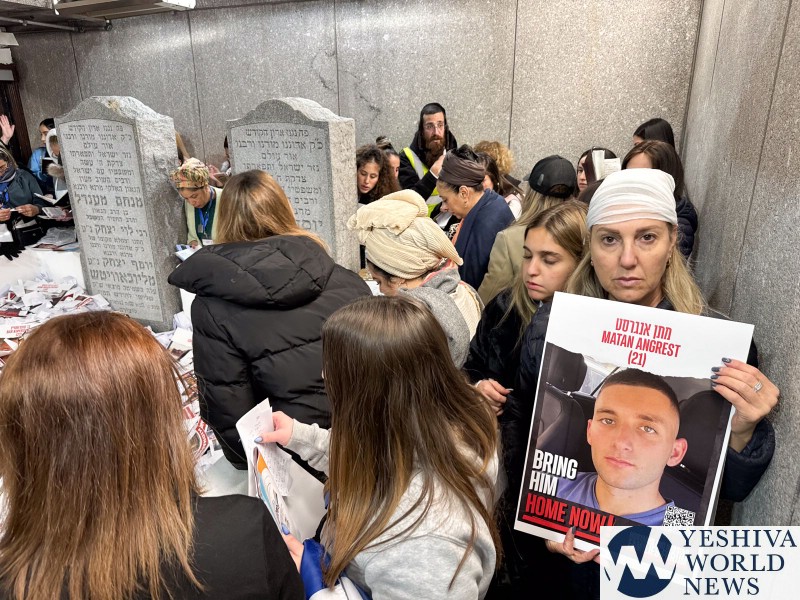

After writing notes bearing their personal prayers, each family member entered the granite mausoleum, many of them bringing photos of their kidnapped loved ones. At the same time, each captive’s name and, per the Jewish custom, their mother’s name, was read out one by one.

A depth of unimaginable pain and worry can be seen in the eyes of each of the hostage’s family members. They are strong, every one of them, but each has a painful story to tell. Here, two brothers speak of their loving mother snatched out of her home in Be’eri, their father having been killed by terrorists trying to defend her. There, a woman cries out “revealed miracles!” when she hears the name of her relative called out for blessing in the long list emanating from within the Ohel.

Just outside the mausoleum, Shai Hartman, a young woman from Ramat Gan, had just finished lighting her seventh candle. The number corresponded to the seven badges she had around her neck, upon which was a picture of each of her seven kidnapped family members. Seven members of Shai’s family are being held by Hamas in some subterranean hell.

“My uncle was murdered; his daughter, her husband and two little children are kidnapped, and my father’s sister—my aunt—is also kidnapped, together with her 12-year-old child,” Hartman enumerates. Only her uncle and aunt, whose last name is Haran, lived in Be’eri; the rest of the family—the Avigdoris and Shohams—had been visiting for the Simchat Torah holiday when the barbarians had barged through the gates. Shai, too, might have been there, but she was unable to be there that day.

What had drawn her to this place, I ask her.

“It feels like a very strong prayer,” Hartman says, the candles she and her fellow family members had lit flickering in the metallic case behind her. “I haven’t cried in two weeks, I think, and inside I just … broke down.”

As they concluded their prayers, the family members returned to the Ohel visitors’ complex, where Rabbi Krinsky gifted each of them with a shekel bill from a thick stack given to him by the Rebbe, as well as a new book of Tehillim (Psalms). Family members flocked to him to get their shekel, moved by the prospect of owning an object that came directly from the Rebbe’s hands, as well as the blessings that it imparts.

Four buses sat on the street outside the cemetery, their gleaming-white panels reflecting the flashing lights of the special group’s NYPD escort. Having prayed inside, a tired Itzik and Sarai Cohen stood ready to board the buses to head to the group’s hotel for the night. The young couple’s cousins, Gali and Ziv Berman, were kidnapped from their home in Kfar Aza. “They were in their home, in their rooms, in their corners of the world and terrorists simply walked in and kidnapped them,” said Sarai.

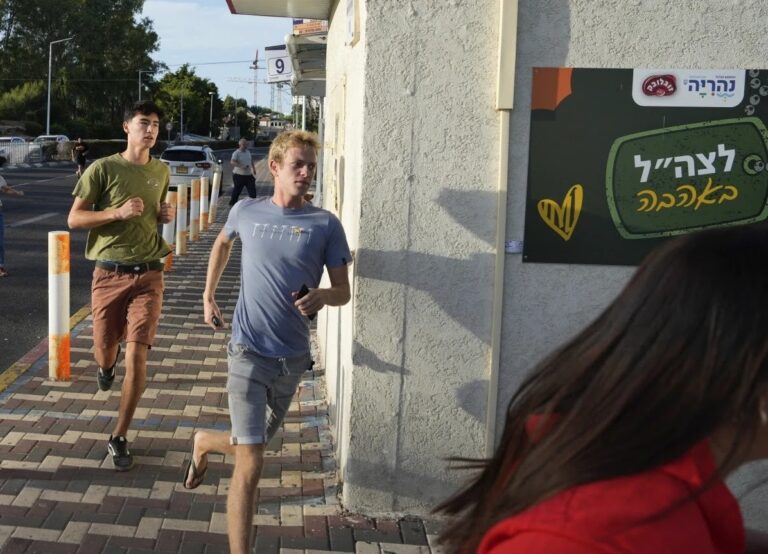

Neither Sarai nor Itzik had ever been in New York before—or the United States, for that matter. Why had they come now? “I felt the Rebbe was calling me,” said Itzik. His wife had heard about the trip from a Chabad rebbetzin in their hometown of Nahariya, on the coast of Israel’s north.

“There are no words for the feeling I felt inside the Ohel, near the Rebbe,” said Sarai. “You feel like you’re not alone.”

“And,” her husband added, “that with G‑d’s help it truly will turn out good.”

(YWN World Headquarters – NYC)

10 Responses

May all their true heartful tefilos be niskabel and soon see yeshuos v’nifla’os.

היפלא מהשם דבר

Hopefully, their emunah and tefillos will bring a positive outcome. I cannot imagine what they are going through for weeks with no end in sight.

Does the Rebbe have time to read all those posters?

yeah keep on doing this always no matter how long it might take u

I see people kissing the tombstones and other stuff. When visiting please do not transgress the biblical prohibition of: Doresh el hameitim.

Rather, pour you heart DIRECTLY to The Almighty and ask b’zchus the tzadik/tzadeket buried there and may that neshama allowed to be a Melitz Yosher (direct advocate) to also help in you interceding your request.

Pine Lake Park, the Rebbe used to get more mail than that every day, and he managed to read it all. And that was while he had the physical limitations of a body; now that he has shed those limitations, the Zohar says that he is present in all worlds more than he was in his lifetime. צדיקא דאתפטר אשתכח בכולהו עלמין יתיר מבחיוהי. So he is surely able to pay attention to each of the hostages individually and to intercede with HKBH for them. Now it remains, as always, for HKBH to do His part, and as always He knows best.

Wow.

Hard to say any words.

This is so important.

Thank you to those who arranged.

May Hashem accept the tefillos of His children!!!

Sad to see nonsensical comments on such a heartbreaking piece….

jpa, I understand that you personally pasken like some of the more recent poskim who ruled that one shouldn’t pour out their heart to the tzaddik buried there, instead directly to Hashem.

It’s possible that they follow the many major poskim (including most older sources, such as Gemara, Midrash and Zohar) who rule that one should ask the tzaddik buried there to beseech Hashem for mercy. They explain extensively why this is NOT doresh el hameisim.

JPA, the Zohar says explicitly that “doresh el hameisim” means resho’im, who are considered dead even when they happen to be breathing, and it does NOT apply to tzadikim, who are considered alive even if they happen not to be breathing.