When Yousef’s wife and their four children boarded a July 15 flight in San Diego to attend her brother’s wedding in Afghanistan, they were looking forward to a month of family gatherings. It was long overdue — the coronavirus pandemic prevented them from traveling earlier.

Their return ticket was Aug. 15, two days before their children’s school year began in the San Diego suburb of El Cajon.

But the Afghan-American family found themselves dodging gunfire and trying to force their way into the crowds of thousands ringing the airport in Kabul after Afghanistan’s government collapsed and the Taliban seized power.

Yousef’s wife and children were among eight families from El Cajon who found themselves trapped after U.S. troops raced to evacuate Americans and allies and then left the country. Yousef asked that only his first name be used because he still has family in Afghanistan who could be at risk.

All but one of the families got out with the help of the Cajon Valley Union School District and Republican Rep. Darrell Issa, whose district includes El Cajon, a city with a large refugee population. The families had traveled on their own over the summer to see relatives and were not part of an organized trip.

Several of the families, accompanied by Issa and school officials, spoke to reporters Thursday for the first time since they returned, recounting their harrowing experience.

The parents described running with their kids as gunfire whizzed overhead. One father said he was beaten by the Taliban. They said they were blocked at Taliban checkpoints.

They said they are grateful to be back but their children have suffered nightmares, and they worry about the family that was unable to get out, along with countless others still stuck there, including distant relatives.

“My kids are now safe at home right now thanks to God and all of you,” Yousef said.

But he asked people not to forget about so many others, including U.S. citizens, green card holders and Afghans who are at risk for helping the American government. He held in his hand a folder that he said contained the documents of 30 people who qualified for a special immigrant visa and should be in the United States but are still in Afghanistan, desperate to escape.

President Joe Biden has said between 100 and 200 Americans were left behind when U.S. troops completed their withdrawal Aug. 31, many of them dual citizens. The State Department has given no estimate for the number of green card holders nor the number of Afghans who remain who helped the U.S. government during the 20-year war and were recipients of a special immigrant visa to come to the United States.

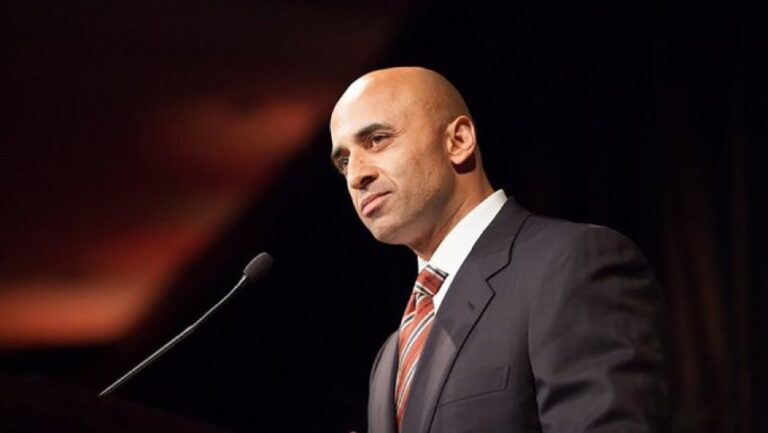

Issa said he believes the number to be much higher for U.S. citizens and the others. Many of the families he helped get back to California in the past week are green card holders. Some are U.S. citizens.

“We’re delighted to have these kids back in school and their parents united, but we also know that there’s a lot more work to do,” Issa said.

Yousef said he felt helpless being in California, thousands of miles away, fearing the life they had built would come to a halt and his wife and children would be trapped in the country ruled by the Taliban. He, his wife and children are all U.S. citizens. They came to the United States on a special immigrant visa after Yousef worked for the U.S. government in Afghanistan.

After they failed to get into the airport on Aug. 15, his wife and kids returned to their relative’s home.

Yousef alerted his family from El Cajon that the U.S. Embassy in Kabul was advising people not to go to the airport because of threats.

Eight hours later, suicide bombers set off explosions at the airport, killing 13 U.S. troops and more than 170 others.

Yousef said Issa’s team arranged a time for his family to go to the airport with an escort from U.S. authorities.

“It was like a situation room,” Yousef said of talking to Issa’s team while navigating his family through the chaos from afar. “I was sitting here talking to them. They were sending their locations and stuff like this.”

His family returned home Friday. The first thing he did was take them to IHOP, their favorite restaurant.

He hopes more of those happy moments will overtake the traumatic memories his kids hold. His 7-year-old son, his youngest, has been talking about the violence.

“They are talking about it, about the gunfire, and being scared of the Taliban, but we hope they forget all that” and return to their life as regular American kids, Yousef said.

(AP)