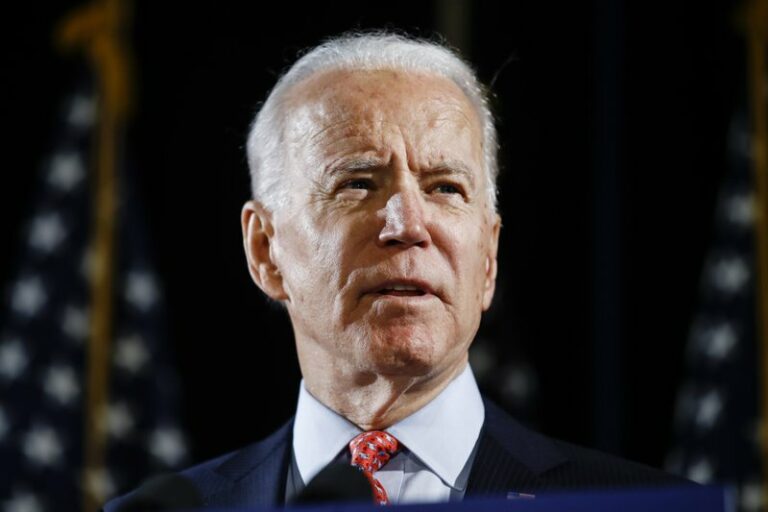

Joe Biden faces the most important decision of his five-decade political career: choosing a vice president.

The presumptive Democratic presidential nominee expects to name a committee to vet potential running mates next week, according to three Democrats with knowledge of the situation who spoke on the condition of anonymity to discuss internal plans. Biden, a former vice president himself, has committed to picking a woman and told donors this week that his team has discussed naming a choice well ahead of the Democratic convention in August.

Selecting a running mate is always critical for a presidential candidate. But it’s an especially urgent calculation for the 77-year-old Biden, who, if he wins, would be the oldest American president in history. The decision carries added weight amid the coronavirus pandemic, which, beyond its death toll, threatens to devastate the world economy and define a prospective Biden administration.

“We’re still going to be in crisis or recovery, and you want a vice president who can manage that,” said Karen Finney, a Democratic strategist who worked for Hillary Clinton’s 2016 campaign. The vice president is “always important,” Finney added. But she pointed to Biden’s role in the Obama administration’s 2009-10 recovery efforts as evidence that a crisis makes the choice of a running mate an even “more important decision than usual.”

Biden faces pressure on multiple fronts. He must consider the demands of his racially, ethnically and ideologically diverse party, especially the black women who propelled his nomination. He must balance those concerns with his stated desire for a “simpatico” partner who is “ready to be president on a moment’s notice.”

The campaign’s general counsel, Dana Remus, and former White House counsel Bob Bauer are gathering information about prospects. Democrats close to several presumed contenders say they’ve not yet been contacted.

Biden has offered plenty of hints. He’s said he can easily name 12 to 15 women who meet his criteria, but would likely seriously consider anywhere from six to 11 candidates. He’s given no indication of whether he’ll look to the Senate, where he spent six terms, to governors or elsewhere.

Some Biden advisers said the campaign has heard from many Democrats who want a woman of color. Black women helped rescue Biden’s campaign after an embarrassing start in predominately white Iowa and New Hampshire. Yet there’s no firm agreement that Biden must go that route.

“The best thing you can do for all segments of the population is to win,” said Biden’s campaign co-chairman Cedric Richmond, a Louisiana congressman and former Congressional Black Caucus chairman. “He has shown a commitment to diversity from the beginning. But this has to be based on, like the VP says, who he trusts.”

Biden has regularly praised California Sen. Kamala Harris, a former rival who endorsed him in March and campaigned for him. When she introduced him at a fundraiser this week, Biden did little to tamp down speculation about her prospects.

“I’m coming for you, kid,” he said.

He’s also spoken positively of Stacey Abrams, who narrowly missed becoming the first African American female governor in U.S. history when she lost the 2018 Georgia governor’s race.

Yet those two women highlight Biden’s tightrope. At 55, Harris is talented and popular with Democratic donors, a valuable commodity for a nominee with a fundraising weakness. But she’s also a former prosecutor who faces the same skepticism among progressives as Biden. Meanwhile, her home state is already firmly in the Democratic column and could make her an easy target for Republicans eager to blast the party as too liberal.

Abrams, 46, is a star for many younger Democrats, a group Biden struggled to win over in the primary. And she could help turn Georgia into a genuine swing state. But the highest post she’s ever held is minority leader in the Georgia House of Representatives, a possible vulnerability in a time of crisis.

Paul Maslin, a Democratic pollster based in the battleground state of Wisconsin, said it will be impossible for Biden to please everyone.

“You can ask too much of a vice president pick to bridge everything — ideology, generational gap, gender, race, experience,” he said. “There’s going to be something wrong with every one of these choices.”

New Mexico Gov. Michelle Lujan Grisham is Democrats’ only nonwhite female governor. Former Senate Majority Leader Harry Reid of Nevada has reportedly vouched for his state’s Latina senator, Catherine Cortez Masto. Illinois Sen. Tammy Duckworth is a veteran who lost limbs in combat. She’s of Thai heritage and has notably jousted with President Donald Trump. And Rep. Val Demings, a black congresswoman from the swing state of Florida, helped lead the House impeachment efforts against Trump.

Yet all four women are relative unknowns nationally.

Biden could go beyond Washington to Gov. Gretchen Whitmer of Michigan, one of the three Great Lakes states that delivered Trump his Electoral College majority in 2016. She’s won plaudits during the pandemic and meshes with Biden’s pragmatic sensibilities, winning her post in 2018 with promises to “fix the damn roads.”

But it’s not clear that a 48-year-old white woman from the Midwest brings Biden advantages he doesn’t already have or can’t find elsewhere.

It’s a similar conundrum for others, including Minnesota Sen. Amy Klobuchar, a former rival who fits seamlessly with Biden’s politics. Massachusetts Sen. Elizabeth Warren, meanwhile, could offer a bridge to progressives, but several Democrats said her age, 70, is a bigger liability than potential policy differences with Biden.

Several African American advocates and progressive leaders said the Democratic ticket’s policies and empathetic appeals are what’s most important.

Black voters “have to trust the messenger,” said Adrianne Shropshire, executive director of Black PAC, and “a black woman could stand up and have moral authority to lead on those big issues facing the country right now.”

But she said that doesn’t mean a white, Asian or Latina vice presidential nominee couldn’t “speak to the systemic issues, the structural issues that allow for inequalities to persist.”

(AP)