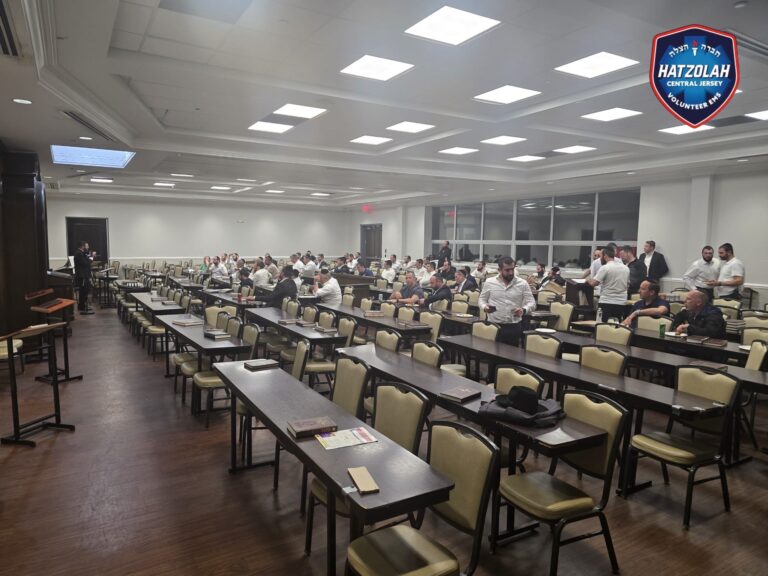

Every month, a hundred or so people crowd the lobby of the Arlington Free Clinic, clutching blue tickets to enter a health-care lottery. Uninsured and ailing, they hope to be among the two dozen who hit the jackpot and are given free care.

Every month, a hundred or so people crowd the lobby of the Arlington Free Clinic, clutching blue tickets to enter a health-care lottery. Uninsured and ailing, they hope to be among the two dozen who hit the jackpot and are given free care.

Some might think the lottery’s days are numbered, given that the insurance expansion under President Obama’s health-care law is taking effect in January. But clinic officials say the lottery will stay because demand for their services is likely to be as high as ever. “We will be business as usual,” said Nancy Sanger Pallesen, the clinic’s executive director.

The Affordable Care Act, the most sweeping health care program created in a half century, is expected to extend coverage to 25 million Americans over the next decade, according to the most recent government estimates. But that will still leave a projected 31 million people without insurance by 2023. Those left out include undocumented workers and poor people living in the 21 states, such as Virginia, that have so far declined to expand Medicaid under the statute, commonly called Obamacare.

“The law will cut the number of the uninsured in half,” said Matthew Buettgens of the Urban Institute. “This is an important development, but it certainly isn’t the definition of universal.”

As a result, while hospitals and other providers gear up to handle an influx of Americans who will be newly insured as of Jan. 1, many of the nation’s 1,000 free clinics, which cater to the uninsured and are financed mostly by private donations, are redoubling efforts to help those bypassed by the law. The trend shows both the limits of the law and the way it is affecting nearly every corner of the health-care system, sometimes in little-noticed ways.

Some of the free clinics are planning to step up their focus on undocumented workers, who won’t be permitted to buy insurance on the new online marketplaces and are expected to become a larger share of the uninsured. Other clinics, seeking to fill what they see as a major gap in the law, are considering offering free dental care.

Andre Sokol, a 59-year-old unemployed carpenter, is an example of someone who won’t be helped by the law and will continue to rely on the Arlington clinic, which, at an given time, provides care to about 1,600 people. He lost his health-care benefits when he left his job in the construction industry several years ago to care for his longtime girlfriend, who was diagnosed with ALS, and his mother, who was battling dementia. Two years ago, the women died within two months of each other. Sokol had no job, no income and no place to live.

In January, Sokol had quadruple bypass surgery at Virginia Hospital Center, which absorbed the costs. He didn’t qualify for Medicaid because Virginia doesn’t allow single men, no matter how poor, on Medicaid, unless they’re disabled. The state has one of the strictest eligibility standards in the country. That would change if the state expanded its program under the health law.

At the same time, Sokol’s income is too low to allow him to get federal subsidies to help pay for a private policy on the exchange. (The law assumed people with incomes below 100 percent of the poverty level, or about $11,500, would be covered by Medicaid, but many states balked at enlarging their programs after the Supreme Court said the expansions were optional.) Arlington Free Clinic officials said about half of their patients are in the same situation: They are below the poverty line but aren’t eligible either for Medicaid or subsidies to buy insurance.

After Sokol had surgery, the Arlington clinic agreed to take him on as a patient, as part of an agreement with Virginia Hospital Center. That agreement is one way people can become patients at the clinic; other patients come in by way of the lottery or via referrals from homeless and domestic-abuse shelters.

“Most of our members would love to go out of business and close their doors if there was a program that ended uninsurance,” Nicole Lamoureux Busby, executive director of the National Association of Free and Charitable Clinics, said. “But this isn’t universal health care. We’re not planning to see a dramatic decrease in our patients.”

Busby said that many of the clinics she works with are facing an additional hurdle with the health law: Convincing private donors that they will still play a crucial role after millions gain coverage.

“So many listen to the news and hear a 24-second sound bite that says everyone is getting coverage,” she said. “The donors may think we don’t need their funds.”

An analysis by the Kaiser Family Foundation predicted that the uninsured rate in Arlington County would fall from 12.4 to 7.4 percent after the health law is fully implemented in 2022. The foundation estimated that 14,000 people would remain without insurance, down from the 24,000 people currently lacking coverage.

The Arlington Free Clinic, which was founded in 1994, is staffed by doctors who volunteer their time when they aren’t at their regular jobs. To be eligible for the clinic, individuals must be over 18, live in Arlington County and earn less than 200 percent of the poverty line, or about $23,000 for an individual. They must also have been in the United States for at least a year.

On a recent Tuesday, the line for the lottery went around the block. It included a wide range of patients, including young children and the middle-aged who spoke English, Spanish, Arabic and Mandarin and other languages.

“I need a doctor for a lot of things,” said Ebtsam Ibrahim, a 46-year-old Egyptian woman and mother of four. She said she has had a toothache for two years but hasn’t seen a dentist because of the cost. She was trying for the third time to win the lottery.

Nazmun Nahar, a 33-year-old mother of three, arrived cradling her one-year-old daughter in her arms. She and her husband are Bangladeshi immigrants who became American citizens over a decade ago.

Because Nahar’s husband makes about $30,000 a year working at Subway, the family of five would likely qualify for generous subsidies to buy private health coverage under Obamacare. But like many of the lottery hopefuls, Nahar knew little about the law or how it would work.

“I just heard a little about it, but nobody explained it to me,” she said.

Jan Strucker, 59, was one of the few people who was aware of the new insurance marketplaces. A retired nurse, she lives on about $20,000 a year in worker’s compensation. She has serious health issues, and may soon need surgery. She figures she would be eligible for subsidies under the law. But that means she needs to wait until October to enroll, and coverage won’t kick in until January.

“This is ridiculous. This is shameful,” Strucker said. “And we’re only seven minutes from the White House.”

By mid-morning, the winning lottery tickets had been selected for 28 participants. A beaming Ibrahim, the Egyptian mother, was among the winners. A husband and wife from Russia also won one ticket that day. Each insisted that the other be the first to take advantage of the free health care, moving some clinic staff members to tears.

Lottery winners must go through an eligibility screening before their first appointment with a doctor, typically weeks later.

The other people who took part in the lottery, including Nahar and Strucker, went home empty-handed. Some will qualify for benefits under the health law. Others will likely return to the lottery, hoping to land a slot at the clinic.

Vidal Grajeda, 68, a retired painter and landscaper who previously won a spot through the lottery, was with his wife, Nicolasa Grajeda, 64, who took part in the lottery but did not win.

“I’m a patient and very grateful to the clinic,” he said. He doesn’t qualify for Medicare because he didn’t work long enough in the United States. At the clinic, he receives treatment for diabetes, high cholesterol, high blood pressure and knee problems. He asked the clinic’s director of clinical administration, Jody Steiner Kelly, whether the clinic will be open and working after Oct. 1, when people can start enrolling in coverage offered under Obamacare.

“Yes, the clinic will be here,” replied Kelly.