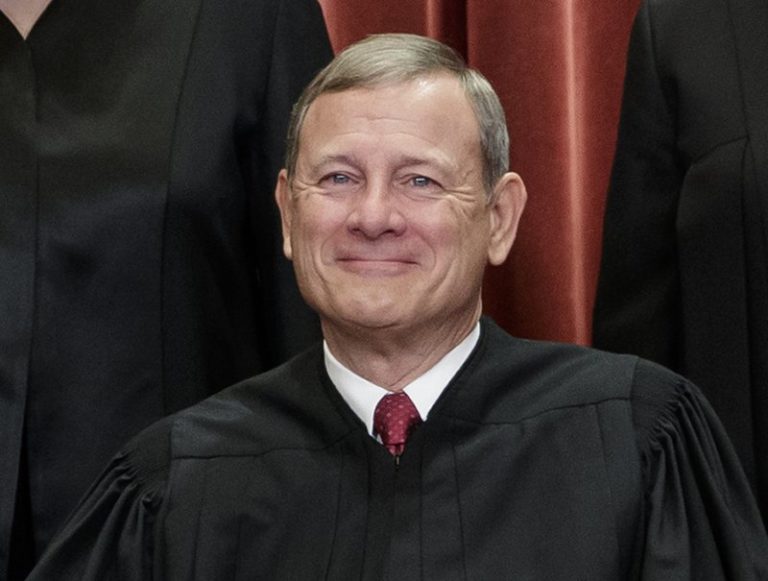

Just hours after Chief Justice John Roberts handed Republicans a huge victory that protects even the most extreme partisan electoral districts from federal court challenge, critics blasted him as worthy of being impeached, a politician who should run for office and a traitor.

But the attacks came from President Donald Trump’s allies and their anger was directed not at the Supreme Court’s partisan gerrymandering ruling, but at the day’s other big decision to keep a citizenship question off the 2020 census, at least for now. Trump tweeted from Japan that the census citizenship decision was “ridiculous.”

What good is a high court conservative majority fortified by two Trump appointees, the critics seemed to be saying, if Roberts is not prepared to use it?

That’s not how Roberts would characterize the court he now leads in name and as the justice closest to the center of a group otherwise divided between conservatives and liberals. He has talked repeatedly about the need to counter perceptions that the justices are just politicians in black robes, beholden to the president who appointed them.

The flurry of action came at the end of a Supreme Court term in which the court welcomed a new justice, Brett Kavanaugh, who narrowly survived the most tumultuous confirmation hearings in nearly 30 years. The justices now begin a three-month summer recess.

The court seem determined to maintain as low a profile as possible once Kavanaugh joined the bench in early October, finding a variety of ways to keep hot-button topics like abortion, guns, immigration and gay rights, that might divide conservatives from liberals, off the term’s calendar.

“This tactic may have been an effort to keep things relatively quiet” following the Kavanaugh nomination, said Josh Blackman, a law professor at the South Texas College of Law in Houston.

But one result of putting off some major decisions in Kavanaugh’s first term is a docket crammed with guns, immigration, gay rights and probably abortion in a session that begins in the fall and will come to a head in June 2020, amid the presidential election campaign.

So far there is only a partial answer to the big question of how far and fast the court will move to the right now that the more conservative Roberts had taken the place of Justice Anthony Kennedy, who retired last year, as the swing justice.

In the case of partisan gerrymandering, Roberts closed the federal courthouse door to lawsuits, a decision that mainly benefits Republicans whose districting plans had been challenged in several states. On the death penalty, the five conservatives appear much less willing to entertain calls for last-minute reprieves from execution. And in two cases the court divided along ideological lines in overturning precedents that had been on the books for more than 30 years.

But Roberts was unwilling to join the conservatives to allow the citizenship question to proceed, although it is not yet clear whether the administration will continue pressing the legal case for the question. The reaction to the census ruling was swift. Former Trump aide Sebastian Gorka called Roberts “a traitor to Constitution.” American Conservative Union president Matt Schlapp called for Roberts’ impeachment. Fox News host Laura Ingraham tweeted that “Roberts should quit and run for office.”

The chief justice also declined to be the fifth conservative vote to overturn two past high court decisions about the power of federal agencies, and joined the liberals in ruling for an Alabama death row inmate who suffers from dementia. In emergency appeals, Roberts was the fifth vote to keep Trump from requiring asylum seekers to enter the country at established checkpoints and the fifth vote to prevent Louisiana abortion clinic regulations from taking effect.

Twenty-one decisions, or nearly a third of all the cases the court heard since October, were by 5-4 or 5-3 votes. But of those, only seven united the conservatives against dissenting liberals. In 10 others, the cohesive bloc of liberals attracted the vote of a conservative justice.

The lack of high-profile cases undoubtedly contributed to the relatively small number of ideologically divided outcomes, said David Cole, legal director for the American Civil Liberties Union, which was on the winning side of the citizenship case and the losing side of the gerrymandering one.

Cole said the 5-4 decisions that cross ideological lines “send a message that this is a court that is not just determined by partisan ideology, but is applying law.”

Roberts sought to reinforce that perception of the court in comments in November, speaking out after Trump called a judge who ruled against his asylum policy an “Obama judge.” Roberts responded: “We do not have Obama judges or Trump judges, Bush judges or Clinton judges.” Commenting on the day before Thanksgiving, he said an “independent judiciary is something we should all be thankful for.”

It could be several years before the impact of a more conservative court, assuming no changes in membership, becomes clear.

But one fear among the liberal justices, and liberals more generally, is a push to restrict if not overturn abortion rights the Supreme Court first declared in the Roe v. Wade decision in 1973. At least one conservative justice has the decision in his sights. Justice Clarence Thomas at one point this term labeled it as “notoriously incorrect.”

The first term of any new justice often has fewer big cases than normal, but the court’s desire to stay away from controversy was heightened by Kavanaugh’s difficult confirmation following allegations he sexually assaulted a woman when they were both in high school. He denied doing anything improper. When he arrived at the court, his colleagues seemed to welcome him warmly. Justice Elena Kagan, his neighbor on the bench, joked with the new justice and made a point of shaking his hand at the end of his first day of arguments.

Kavanaugh’s parents were often in the courtroom, especially when their only child announced an opinion.

The new justice “stuck pretty close to the chief in a lot of cases,” said Supreme Court advocate Nicole Saharsky. Kavanaugh was a confident, straightforward questioner during arguments and didn’t seem to be “making waves in any significant respect,” Saharsky said. At the same time, she said it’s hard to tell much about a justice based on only a year’s worth of data.

One surprise was that Kavanaugh and Justice Neil Gorsuch, two Trump appointees, who have known each other since high school, found themselves on opposite sides of 18 decisions. They voted together, however, in the biggest cases on gerrymandering and the citizenship question.

(AP)