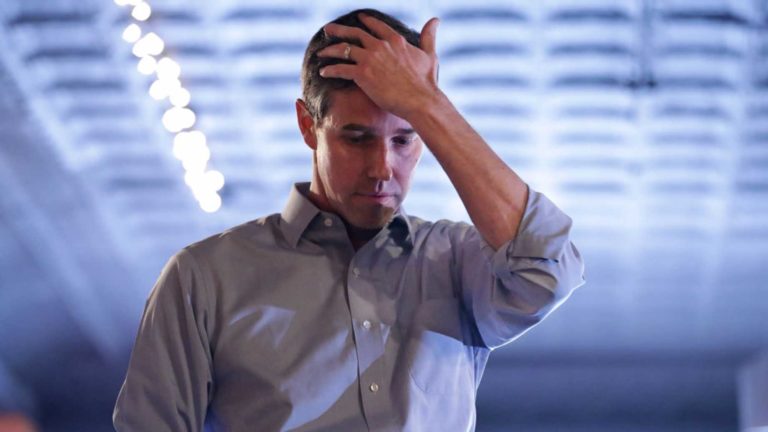

Democrat Beto O’Rourke uses his home state as a cautionary tale, ticking through Texas’ Republican-backed policies as warning flags for the rest of the country.

Mayor Pete Buttigieg mentions once worrying about how coming out as gay in deeply Republican Indiana might have cost him re-election, even in his more moderate college town of South Bend.

Sen. Kirsten Gillibrand speaks of evolving away from defending gun rights during her early years in Congress representing a conservative House district in upstate New York and notes, “I have uncles who voted for Trump. I get it.”

There are 20-plus Democrats competing for the party’s 2020 presidential nomination, but only five are from reliably GOP areas. Members of this select group are trying to balance their home turf stories, pitching themselves as uniquely suited to win over voters who previously backed President Donald Trump while also pointing out what they view as the shortfalls of Republican government.

“When you’re coming from a state like that, you’ve got to pick your spots to try to figure out where you can have a little bit of influence,” said Russell Ott, a Democratic state representative in South Carolina, which holds the South’s first presidential primary but has no Democratic statewide officeholders. “I think that’s something people appreciate.”

O’Rourke, who represented El Paso, on the Texas border with Mexico, in Congress for six years says he will work with both parties and loves his state. But he isn’t shy about ripping its politics.

He decries Texas for championing the death penalty, failing to expand Medicaid under the Obama administration’s health law and having one of the nation’s lowest voter turnout rates — due, he says, to strict voter ID rules. O’Rourke also says jails are among Texas’ top providers of mental health care and people deliberately get arrested to seek treatment. He says Texas is one of many places without laws prohibiting employers from firing people for being gay.

“It’s a defense in a court of law in Texas if you’ve killed someone of the same sex because they came on to you in a bar or on the street,” O’Rourke tells campaign audiences, noting that Texas and other states don’t prohibit what LGBT activists call “gay panic defense” as a mitigating argument in criminal court.

Fellow Texan Julian Castro, ex-San Antonio mayor and Obama administration housing chief, is more critical of Trump than the Lone Star State, and praises his heavily Hispanic city.

“I came up in San Antonio that was almost 50-50 Republican/Democrat,” Castro said, though politics there now are far more liberal. “I had to learn how to talk to the other side, consider their ideas, find common ground where we could.”

Former Alaska Sen. Mike Gravel says he’s running for president to push the field farther left — defying his home state, which hasn’t voted Democratic for president since 1968.

Conversely, many of the race’s top blue-state Democrats play up their stomping grounds.

California Sen. Kamala Harris said “I am so proud to be a daughter of Oakland, California” and has talked about how her East Bay roots instilled a sense of community and optimism. Her state’s governor, Gavin Newsom, isn’t running but he also isn’t afraid to say that California should be the inspiration for 2020 Democrats: “We’re in the most Un-Trump state in America.”

Sen. Elizabeth Warren champions being an Oklahoma native who can appeal to rural voters, but offers a liberal populist message most representative of the Democratic bastions of the state she represents, Massachusetts. And Vermont Sen. Bernie Sanders proclaims, “I know where I come from and that is something I will never forget” when speaking about his Brooklyn upbringing.

Those 2020 Democrats from Republican strongholds may have an advantage over their competitors, however, because they won’t have to answer for more liberal-policies common in Democratic areas. Such political baggage may not hurt during the primary but could in the general election against Trump.

Buttigieg largely refrains from criticizing his native state but sees “coming from a fairly blue city in a purple county in a red state” as an advantage.

“If nothing else, it gives you a different vocabulary,” Buttigieg said. “A lot of times, even when I have a strong progressive message, I think I have an instinct for how to convey that in a way that’s inclusive and then reaches to more people.”

Gillibrand came to the House in 2007 representing a conservative district and once signed an amicus brief to the Supreme Court arguing for overturning a District of Columbia handgun ban.

She now says she was wrong but that learning from the issue has made her stronger, and she can now better relate to those voters that Democrats need to win back from Trump. Gillibrand notes she was introduced during a recent visit to Iowa as being from “the Iowa part of New York.”

“The Democrats in these places are a lot like my Democrats” in New York, she said. “They fight really hard. They know how hard it is to win, but they really never give up and they organize and they’re ambitious and they try really hard.”

(AP)