President Donald Trump wasted no time before seizing on last week’s report by the Justice Department’s internal watchdog on misconduct allegations against the FBI’s former No. 2 official, Andrew McCabe. Trump tweeted it was proof that his archrival James Comey, the former FBI director, “totally controlled” McCabe.

But the report by Inspector General Michael Horowitz said no such thing. In fact, it depicted clashing accounts of a conversation they had that contributed to McCabe’s dismissal.

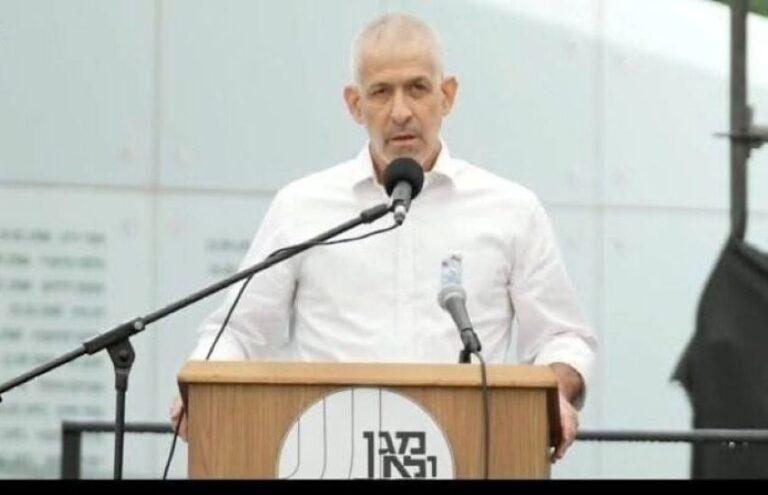

It wasn’t unusual for Horowitz to see his actions — or his own credibility — caught up in Washington’s political storms, despite the apolitical reputation he has cultivated over six years on the job. Trump has disparagingly called Horowitz an “Obama guy” even as McCabe’s lawyers have decried the report and investigative process as unfair. No matter the opinion, there’s no doubting the impact of the work: It helped lay the groundwork for McCabe’s firing and opened him to torrential criticism by Trump and his supporters.

The controversies he has endured are likely nothing compared to what awaits him in coming weeks when he announces the findings of his review into the FBI’s handling of the Hillary Clinton email investigation. The report will inflame the debate about whether FBI actions during the campaign affected the race’s outcome. And Trump’s friends and foes will inevitably scour for any nugget that can undermine his criticism of their side, and Horowitz himself.

Charles McCullough, a former intelligence community inspector general who referred the Clinton emails to the FBI, said he believes Horowitz’s report will be “absolutely thorough and completely accurate.”

Still, he said, Horowitz “will be in the same vortex that we were in, and you just have to manage that as best as you can because of the politics.”

Horowitz declined to comment, through a spokesman.

The Clinton report is unquestionably Horowitz’s most politically consequential case, but it’s not his first high-profile investigation.

He spent years as a federal prosecutor in the powerful Southern District of New York as chief of its public corruption unit, where he built cases against crooked police officers. He later served in top Justice Department roles under Presidents Bill Clinton and George W. Bush.

Attorney Josh Berman, a close friend who has played basketball and softball with him, recalled that Horowitz had anticipated departing at the end of the Clinton administration and had packed up his office as chief of staff to the criminal division head. Yet, unexpectedly, he was asked to stay on.

“He is the kind of guy who plays it straight, plays it fair, doesn’t let politics … play into his decision-making,” Berman said.

President Barack Obama nominated him for inspector general in 2011, and he quickly dived into big scandals.

Five months after he took the position came a report on the botched gun-tracking operation called Fast and Furious. It criticized individual agents and prosecutors and prompted the resignation of a top criminal division official whose supporters say was unfairly maligned by Horowitz’s office. It largely spared from direct attack then-Attorney General Eric Holder and other senior officials. Lawmakers questioned whether he’d held back out of friendship, which he denied.

“The only thing that was going to make my decisions here were the facts and the law, period,” Horowitz said at a 2012 hearing.

His supporters note that while Horowitz was appointed inspector general by Obama, Bush had named him to the U.S. Sentencing Commission. As a watchdog in a Democratic administration, he sometimes enjoyed the support of congressional Republicans performing similar oversight.

“He is the brain trust that we on the Hill have relied on for years,” said Keith Ashdown, former Republican staff director for the Senate Homeland Security and Governmental Affairs Committee. “He’s not just great at what he does for the Department of Justice, he has had an aggressive, important and vital role in shaping the IG community at large.”

As chairman of an inspector general umbrella group, he’s championed the interests of fellow watchdogs. Ashdown recalled Horowitz being the first inspector general to publicly criticize his counterpart at the Department of Veterans Affairs after he subpoenaed a watchdog group in a move other inspectors general privately found aggressive. McCullough said Horowitz supported him during the fracas over the Clinton email referral.

Robert Storch, who was hired by Horowitz and is now the National Security Agency inspector general, called him a nurturing boss who made a point to show interest in his employees despite the job’s long hours and rigorous demands.

“He is a marvelous leader in that sense,” Storch said.

In 2015, Horowitz complained about an Office of Legal Counsel opinion that he felt interfered with his office’s ability to obtain grand jury records, wiretap information and other data normally protected from public disclosure. Justice Department officials were rankled by what they saw as Horowitz’s mischaracterization of the opinion and his criticism of an under-the-radar office. Yet Horowitz succeeded in drawing attention to his stance and secured legislation to ensure the access he wanted.

Horowitz has also been sensitive to media coverage of his office and public perception of its work. After the Justice Department disclosed anti-Trump text messages between FBI agent Peter Strzok and another FBI official, Horowitz issued an unusual statement to make clear his office hadn’t been consulted on whether it approved the release.

Given the public and congressional interest in the FBI’s handling of the Clinton case, there was probably no way Horowitz could have avoided wading in, McCullough said.

“Once you’re tasked to do it, it’s the whole nine yards. You can’t do it halfway.”

The Clinton report has had practical consequences even before its release.

It was Horowitz who flagged the texts from Strzok, who worked on the bureau’s Clinton investigation and later joined special counsel Robert Mueller’s team. Strzok was reassigned.

And it was Horowitz’s office that concluded McCabe hadn’t been forthcoming about having authorized FBI officials to speak with a journalist about an investigation into the Clinton Foundation. The FBI’s internal disciplinary office recommended McCabe’s firing. Attorney General Jeff Sessions dismissed him last month.

McCabe denies misleading anyone. His lawyer, Michael Bromwich, a former inspector general himself, blamed Horowitz for severing the McCabe matter from the rest of the investigation. He says Horowitz and FBI disciplinary officials rushed to complete their work before McCabe’s planned retirement.

(AP)