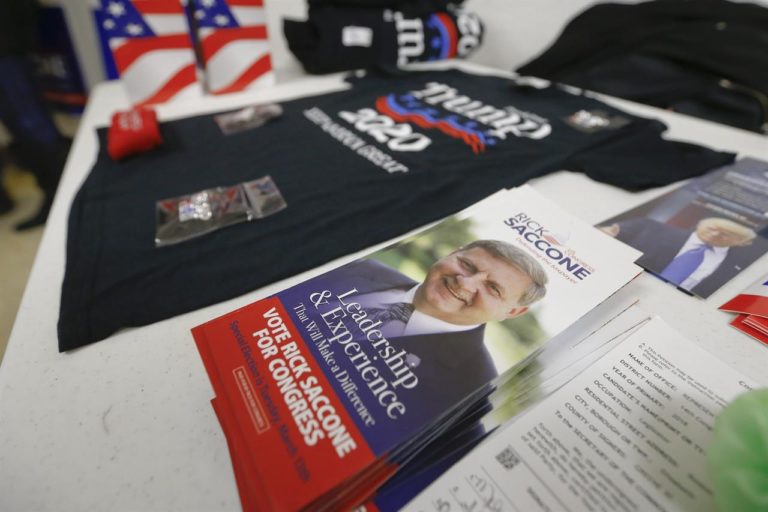

There is no sign of Republican congressional candidate Rick Saccone on Sherwood Drive.

Days before a special U.S. House election in western Pennsylvania, Saccone’s campaign told some residents that he might be knocking on doors that morning. It’s almost 11 a.m. They’re waiting.

“He was supposed to stop by today,” 68-year-old Republican John Debich says, scanning the empty streets of suburban Greensburg from his front porch. “It’s the second time we’ve been avoided.”

Saccone may be President Donald Trump’s strong favorite in a conservative region, but he’s leaning seemingly exclusively on that and struggling with the basics of modern-day politics.

Tuesday’s race will hinge on voter turnout, and the 60-year-old state lawmaker has little organization of his own — at least compared with Democrat Conor Lamb, a 33-year-old former Marine and federal prosecutor who has never before run for office.

Saccone indirectly admitted as much Saturday ahead of the president’s arrival.

“The president’s support is key to attaining victory,” he roared to several thousand backers gathered near the Pittsburgh airport. “There’s no one that I would rather have in my corner that President Trump. Are you with me on that?”

Fearing another special election embarrassment, the White House was sending Trump to rally the party’s core backers. White House counselor Kellyanne Conway campaigned for Saccone on Thursday, though her first appearance at a Pittsburgh “meet and greet” with campaign volunteers attracted fewer than 20 people. Donald Trump Jr. is set to rally voters on Monday.

Former Vice President Joe Biden came to the district this past week for Lamb, but national Democrats didn’t plan to bring in additional high-profile figures in the campaign’s waning days.

Get-out-the-vote operations are the lifeblood of most successful campaigns. But Saccone’s has drawn little energy from within, so he is relying on paid contractors and the national GOP, which has scrambled to pick up the slack.

“We’re doing everything that we need to do to get out the vote and inspire people,” Saccone told reporters this week before a private event with representatives from the oil and gas industry. He added, “All the traditional things, we’re doing.”

Later that day, Lamb marched up and down the hilly streets of Carnegie in the snow to encourage Democrats to vote. Some residents of the working-class Pittsburgh suburb were surprised to see the Democratic candidate at their doorstep.

Josh Jaros and his partner, Kim Zouko, both 36, invited Lamb into their living room, where he played with their 3-year-old daughter for a few minutes before asking them who they were voting for.

“You’ve got our vote. And if you didn’t before, you do now,” Jaros told him.

After knocking on 27 doors, Lamb returned to a nearby campaign office to speak to nearly 40 young volunteers, many of them in high school. They munched on macaroni and cheese and pulled pork as Lamb emphasized the importance of preserving Medicare and Social Security — programs that help people maintain “basic dignity,” he said.

In a brief interview as volunteers buzzed through the two-story office, Lamb insisted that winning elections isn’t “rocket science.”

“We’ve been working really hard to identify who our people are through door knocking and calls. That’s what all these people are doing,” Lamb said. “Election day is going to be like Dunkirk — everybody in their car is going to go out and make sure everybody gets there.”

Some Washington Republicans say Lamb is the superior candidate in a race that would have been an easy GOP victory if not for Saccone’s struggle to raise money and build an aggressive campaign.

The Republican posted only two public events on his Facebook page for the seven-day period before the election. He has run few TV ads in recent weeks. His message, if voters hear it, is focused on his support for Trump, his experience in the public and private sector, his opposition to abortion rights, and efforts to link his opponent to the top Democrat in the U.S. House, California’s Nancy Pelosi.

Saccone does enjoy a base of devoted supporters from the area he represented in the state house, but Pennsylvania’s 18th Congressional District includes 10 times more people.

Trump won the area by nearly 20 percentage points little more than a year ago, but polls now suggest that the Republican and Democrat are essentially tied. The seat has been in Republican hands for the past 15 years.

“Candidates and campaigns matter, and when one candidate outraises the other 6-to-1 and runs circles around the other, it creates real challenges for outside groups trying to win a race,” said Corry Bliss, executive director for the Congressional Leadership Fund, a group aligned with U.S. House Speaker Paul Ryan, which has invested $3.5 million to boost Saccone’s candidacy.

The organization has been active since early January on an aggressive get-out-the-vote operation of its own. Over the last week, 50 full-time door knockers, hired through a private contractor, canvassed the district. They handed out flyers that cast Lamb, a moderate Democrat who has played down his connection to the national party, as a “rubber stamp for Nancy Pelosi.”

Teams from the Koch brothers-backed Americans For Prosperity arrived this weekend to broaden the conservative outreach. The Republican National Committee has spent more than $1 million on its own operation that was expected to reach 250,000 targeted voters — either by phone or in person — by election day, said RNC spokesman Rick Gorka.

Overall, national groups allied with the GOP have spent nearly $8 million on advertising in the race, more than seven times the amount invested by national Democratic allies unaffiliated with the Lamb campaign.

Media trackers report that Lamb has invested at least $3.4 million on advertising, while five pro-Lamb outside groups spent roughly $1.1 million combined

Democrats have overperformed in virtually every contest since Trump took the White House. And the sting of the GOP’s December defeat in Alabama’s special U.S. Senate race is still fresh.

Back on Sherwood Drive, Debich is disappointed that Saccone didn’t show, but he says it won’t affect his vote. He notes that he stapled a Saccone campaign sign to his front lawn so the wind wouldn’t blow it away.

“I’d like to meet him,” Debich says. “I know he’s a busy man. I’ll see him at the Trump rally.”

(AP)