Vayavey es ha’Aron el ha’Mishkan vayasem eis Paroches hamasach vayasech al Aron ha’Eidus ka’asher tzivah Hashem es Moshe (40:21)

In his commentary on our verse, the Baal HaTurim points out that the Torah emphasizes that every aspect of the construction and assembly of the Mishkan was done precisely as Hashem commanded Moshe. In fact, the phrase “as Hashem commanded Moshe” is used 18 times in Parshas Pekudei. As there are no coincidences in the Torah, the Baal HaTurim explains that this number alludes to the 18 blessings recited thrice-daily in the prayers known as Shemoneh Esrei.

I once heard a beautiful and profound insight into the explanation of the Baal HaTurim. Hashem told Moshe (31:1-5) that Betzalel should be in charge of building the Mishkan and its vessels, for He had imbued him with Divine wisdom and with expert artistry and craftsmanship skills. We are accustomed to viewing artists as free-thinking and creative spirits, valuing self-expression over adherence to strict rules and guidelines. As many of the specifications for the Mishkan weren’t absolute and even numerous deviations wouldn’t invalidate it, one might have expected Betzalel, with his “artistic spirit,” to improvise and attempt to “improve” upon Hashem’s blueprint. Therefore, the Torah stresses that he followed each and every instruction down to the smallest detail.

Similarly, many people today complain that they feel constrained by the standard text of our daily prayers, which was established almost 2000 years ago. They feel that as our daily needs change, so too should our expression of them. However, based on the Baal HaTurim’s comparison of the daily prayers to the construction of the Mishkan and its vessels, we may suggest that on a deeper level, he is hinting to us that we need not feel stifled by the repeated expression of our needs and entreaties using identical phrases, as illustrated by the following story.

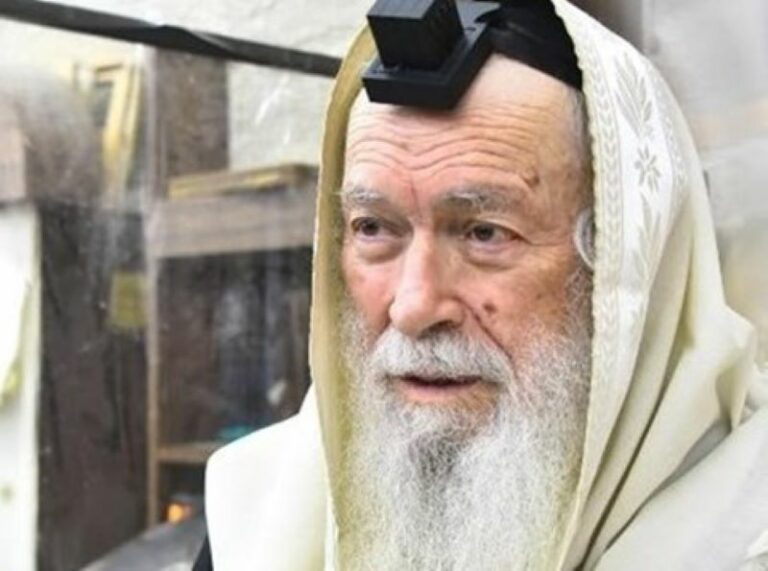

A close disciple of Rav Yechezkel Abramsky once mentioned that an acquaintance of his had recently undergone a difficult kidney transplant. Rav Abramsky sighed, feeling the other Jew’s pain, and then remarked, “I pray every day that I shouldn’t be forced to undergo such a procedure.” The surprised student questioned why he made a special point of reciting this unique prayer daily. Rav Abramsky responded that this request is included in the standard wording of Birkas HaMazon, in which we request that we not come to need matnas basar va’dam – gifts of flesh and blood (e.g. transplants).

The student challenged this explanation, as the simple understanding of the words is that we shouldn’t need monetary gifts from other humans (“flesh and blood”). Rav Abramsky smiled and explained that the Sages incorporated every need we may have into the text of the standard prayers. Any place we find in which we are able to “read in” a special request we have into the words is also included in the original intention of that prayer.

Just as Betzalel followed Hashem’s precise guidelines for the creation of the Mishkan and still found room for creative expression by doing so with his own unique intentions and insights, so too our Sages established the standard wording of the prayers with Divine Inspiration, articulating within them every feeling we may wish to express. Many times, in the midst of a difficult situation, we begin the standard prayers with a heavy heart, only to find a new interpretation of the words which we have recited thousands of times jump out at us. This newfound understanding, which has been there all along waiting for us to discover it in our time of need, is perfectly fit to the sentiments we wish to convey, if we will only open our eyes to see it and use our Sages’ foresight to express ourselves.

Ki anan Hashem al ha’Mishkan yomam v’aish tih’yeh laylah bo l’einei kol Beis Yisroel m’chol mas’eihem (40:38)

The book of Shemos concludes by teaching that the Mishkan was covered by Hashem’s cloud during the day and by fire at night throughout the travels of the Jews in the wilderness. In his commentary on this verse, Rashi curiously adds that even the times of their encampments are also included in the reference to “their journeys.” What lesson is Rashi teaching us?

Rav Moshe Shternbuch suggests that Rashi is symbolically teaching us that there are no interruptions in a person’s service of Hashem. Even at the times when one is forced to take a break, the rest doesn’t constitute a goal unto itself, but rather a means of renewing one’s energy in order to continue with the next journey.

Parshas Pekudei is traditionally read near the end of the yeshiva’s winter z’man, as the students prepare to return home for bein ha’zmanim and the Yom Tov of Pesach. As we conclude the book of Shemos, Rashi teaches us the Torah’s philosophy regarding this intersession. It shouldn’t be viewed as an independent break in the yeshiva calendar, but rather as a link in the chain of personal growth and an opportunity to refresh ourselves in order to return and begin the next z’man with a feeling of enthusiasm and renewal.

Answers to the weekly Points to Ponder are now available!

To receive the full version with answers email the author at [email protected].

Parsha Points to Ponder (and sources which discuss them):

1) In reference to the making of the Tzitz (head-plate) of the Kohen Gadol, the Torah states (39:30) that “they wrote on it ‘Holy to Hashem.'” Why was it necessary for multiple people to inscribe a mere two words on the Tzitz? (Moshav Z’keinim, Taam V’Daas)

2) In the special portion which is read as Parshas Shekalim, Rashi writes (30:12) that a census must be conducted by counting the half-shekels which were contributed by each person because it is forbidden to make a head count. The Gemora in Yoma (22b) explains that when it was necessary to count Kohanim in the Temple, the person in charge would count their fingers instead of their heads. As their fingers and heads are all part of the same body, why is counting one forbidden and counting the other permitted? (Shu”t Torah Lishmah 386, M’rafsin Igri)

© 2013 by Oizer Alport.