The official news agency of the Islamic State labeled the Ohio State student who smashed his car into a crowd and then slashed at people with a butcher knife a “soldier” of the militant group, according to an organization that monitors extremists.

The official news agency of the Islamic State labeled the Ohio State student who smashed his car into a crowd and then slashed at people with a butcher knife a “soldier” of the militant group, according to an organization that monitors extremists.

This posting does not necessarily mean that Abdul Razak Ali Artan acted at the behest of the terror group, which often claims responsibility for attacks in which it had no actual involvement, said Rita Katz, executive director of the SITE Intelligence Group.

Katz said that Amaq’s claim suggested that Artan did not coordinate with the group, but that it had spent time looking at news reports to determine his motivation.

The bloodshed in Columbus on Monday occurred after the Islamic State issued instructions this month about carrying out attacks using knives and vehicles, Katz said. And as long as these instructions are online, similar attacks are likely to continue, she said.

On Tuesday, the Amaq News Agency, which is linked to the Islamic State, also said that the attack was carried out in response to the group’s “calls to target citizens,” the same language used when the group claimed credit for the Minnesota mall stabbings in September.

The Islamic State often claims attacks carried out by people who had no direct connection to the group, and their responses can vary depending on whether they were actually involved.

After the deadly attacks in Paris last year, detailed news releases with video recordings and photos were quickly sent out. It took two days for Amaq to claim credit for the attack in San Bernardino, Calif., last year, saying that “supporters of the Islamic State” had carried out the mass killing. In September, it took a day for Amaq to claim that the attacker who stabbed 10 people in a Minnesota mall was a “soldier” of the group.

Experts say that the Islamic State, also known as ISIS or ISIL, can claim credit for attacks even when it has no involvement in an effort to latch onto the narrative.

Social media groups in favor of the Islamic State had celebrated the attack on Monday after reports emerged about Artan’s possible Facebook post ranting about the treatment of Muslims, but that reaction had ebbed by a day after the violence, Katz said.

According to CNN, the Facebook post apparently written shortly before the attack says that if Muhammad were alive today he would be labeled a terrorist by the western media and that “seeing my fellow Muslims being tortured, raped and killed in Burma led to a boiling point. I can’t take it anymore.”

SITE has also found that several far-right blogs and forums were reveling in the attack, with people posting racist comments as well as making remarks blaming President Obama and criticizing diversity, Katz said.

In the aftermath of a the attack – which authorities said appeared to have been planned – classes resumed at Ohio State on Tuesday morning with sorrow, fear, numbness, and a call for unity.

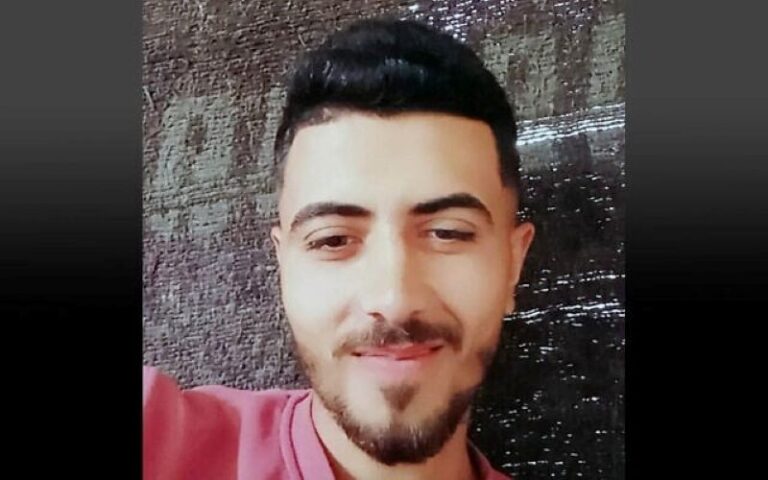

Artan, an Ohio State student whose neighbors in Columbus said was Somali, was shot to death by a university public safety officer within minutes of his outburst, which injured 11 people. Authorities said they did not yet know what motivated Artan to attack, but they said they cannot rule out the possibility of terrorism.

The attack Monday morning, as classes were beginning after the Thanksgiving break, sent crowds of students sprinting to safety while terrified students and professors barricaded themselves in classrooms not knowing what was happening at the flagship state university.

Because the method of the attack was one that the Islamic State had promoted recently, and because law enforcement officials said they were investigating the origins of a social-media post in which Artan appeared to rant about the treatment of Muslims, and because he said in the student newspaper the Lantern that he was scared to pray publicly at Ohio State, some presumed Artan’s motivation stemmed at least in part from his Muslim faith.

The assault “bears all the hallmarks of a terror attack carried out by someone who may have been self-radicalized,” Rep. Adam B. Schiff (Calif.), ranking Democrat on the House Intelligence Committee said in a statement Monday.

That sentiment, which emerged almost immediately after police publicly identified Artan, led to concern from some in the Columbus Somali and Muslim communities that people angered or frightened by the attack might target them for retribution. Some at Ohio State described students and faculty as bracing for the day Tuesday, facing the unknown.

At a time when the country is already deeply divided over issues of immigration, with president-elect Donald Trump having vowed to prevent Muslim extremists from entering the country, the attack was particularly searing.

The university had a message prominently on their home page Tuesday morning: “Together we remain unified in the face of adversity. Today and always, we’re all Buckeyes.”

Community members planned to gather in the evening to promote unity and healing.

While police say Artan was alone during the attack, authorities have not ruled out the possibility that he might have had some form of help, Columbus police chief Kim Jacobs said Tuesday.

“Everybody has a lot of people in their life, and we need to talk to people that knew him and find out what they knew about him,” Jacobs told WOSU public radio. “Were there any signs? Were there any people that he worked with, cooperated with, were perhaps influenced by?”

Investigators seeking a motive for the attack are going to sift through Artan’s online postings as well as what he has said to people who knew him, Jacobs said. She said authorities are looking at a Facebook posting believed to be from Artan to see if it provides insight into what may have prompted the attack.

“I believe that it discusses his feelings about the current status of his faith and some of his troubles,” Jacobs said. “Certainly, that will be looked at, kind of gone over, pored over, to determine whether or not there was a basis there for his actions.”

Columbus has the second-largest Somali community in the country, according to Abukar Arman, a local Somali community leader who also served as the United States’ special envoy to Somalia from 2000 to 2013. Somalis make up the largest immigrant group in the city.

Most of the Somalis arrived in the late 1990s, after fleeing civil war and strife in their home country. Some had initially settled elsewhere in the U.S., but came to Columbus for work, he said.

Horsed Noah, executive director of the Abubakar Assidiq Islamic Center mosque in Columbus near Artan’s home, said that the violence stunned members of the Somali refugee community. “In times like this you have to stand up and explain the true image of Islam,” Noah said. “We must fight against stereotypes. We all share this planet.”

Some student groups posted statements on social media.

On Facebook, there was an outpouring of support for the Somali Students’ Association at Ohio State after the group posted a statement condemning Monday’s violent attack and offering prayers for the victims.

“We know that some will connect this tragedy with the ethnicity or religion of the attacker,” the group said. “Neither our Somali heritage nor our faith condones the harming of innocent people.”

That prompted responses such as, “You don’t need to defend your humanity. You are welcome here.”

“Blessings to you guys,” another wrote. “Columbus wouldn’t be the Columbus I love without you and the richness you bring to it.”

Arman said the group, which has 500 to 600 members, also has been bombarded with hate mail in the past 24 hours.

“Here is where my fear is,” he said. “This will play into further stigmatizing of American Muslims, and those of Somali Muslims in particular because it plays right into the narrative of the president-elect.”

“I write this to you from a place of deep sadness and utter shock after the tragic events that took place yesterday. The tragic incident that happened in OSU. . . . Our police departments will continue to be on alert at all Columbus State locations. The safety of students, faculty members, staff, and visitors is of the highest importance.

Ohio State, like many across the country, has had tensions during a polarizing campaign and after the election.

Fliers advising white women not to date black men, and other white-supremacist ideas, were posted on campus earlier this month, as they were at several other colleges.

OSU student Tony Buss, director of the school’s student government committee on division and inclusion, said he’s heard that Muslims on campus have been verbally harassed. He said his Muslim friends have expressed concern about hate speech in the past year, including some incidents in the past month.

The president of the student government association, and members of the Buckeyes for Trump student group did not immediately respond to requests for comment Tuesday.

Jani said that after the election, hundreds of students reached out to campus leaders with concerns about how they, as immigrants, or minorities, would be treated during a Trump administration. The attack yesterday intensifies all that emotion.

“The whole OSU community just coming to campus today is a bit nervous – whatever their background,” he said. “This was terrorizing for everybody.”

(c) 2016, The Washington Post · T. Rees Shapiro, Susan Svrluga, Abigail Hauslohner, Mark Berman, Matt Zapotosky

2 Responses

Now their DEAD soldier.

Trump was right about vetting immigrants.